- Fisher-Wirth hopes to launch several public projects, including an online series where Mississippians can read and reflect on their favorite poems.

Mississippi’s newly appointed Poet Laureate, Ann Fisher-Wirth, is recovering from a fractured hip. “Right now, the Poet Laureate thing feels like a nice dream,” she explains over the phone.

It’s not the triumphant unveiling she imagined as Poet Laureate. Yet, there may be something almost poetic about Fisher-Wirth’s new chapter from a place of immobility and introspection. Poetry doesn’t require a grand entrance, as she discloses in this feature. It only asks for your willingness to stay in a moment long enough to see it and hear what it has to say.

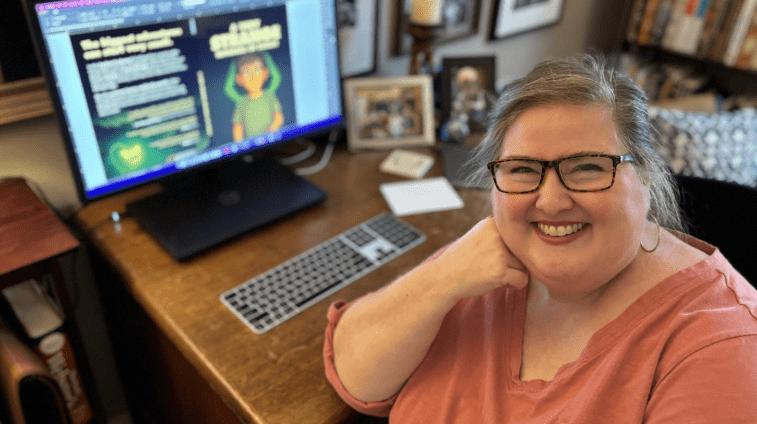

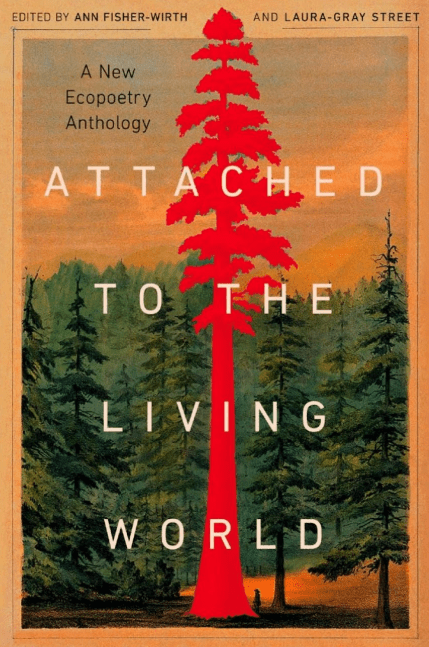

She built her career with creating word pictures and teaching her students how to see. A professor emerita of English at the University of Mississippi, Fisher-Wirth has published seven books of poetry, including Paradise is Jagged, The Bones of Winter Birds, Mississippi (a poetry-photography collaboration with Maude Schuyler Clay), and most recently, Attached to the Living World, co-edited with Laura-Gray Street, a follow-up to their acclaimed Ecopoetry Anthology. Each speaks in the dialect of place, ecological memory, and spiritual urgency.

“I write a lot about place,” she says. “I wrote a book about living in Sweden called Carta Marina. But the place I’ve written most about now is Mississippi..”

Ecology as Intimacy

Fisher-Wirth elaborates on how being immersed in poetry is to experience nature outside ourselves: the music of tiny creatures hidden deep in the woods, the labor of lichen drawing carbon from the air, protecting us without us being aware. “But we don’t care about what we don’t see,” she says. “Poetry makes us see.”

Awareness breeds care, and care often leads to action, so poetry is the moral architecture behind Fisher-Wirth’s lifelong commitment to the environment. “Poetry takes that world seriously. It’s not just a kind of coding background for us because it’s trying to understand that we are absolutely interrelated with and embedded in the environment. It’s a closed system of reciprocal relationships,” she says. Just as there is no line between aesthetics and activism, a poem draws no line between being a creative wonder and a tool for survival. “I think poetry can awaken our hearts, imaginations, and intelligence to make us more aware. Then, once we are, we are likely to take action.”

Her latest co-edited anthology, Attached to the Living World, includes poems on forced child slavery in the cacao industry, the destruction of the Amazon, the Standing Rock protests, and fracking. “More and more poets are finding it impossible to ignore the environmental situation,” she says. Themes are evolving, but also the voices and forms: more poets of color, more LBGTQ writers, and more experimentation shaping the poem on the page. “More are realizing the situation in this world is beyond dire. Poets ask themselves all the time: what good is poetry? What can poetry do?”

On Crafting Poems

Despite the accolades, including Fulbright fellowships, a Mississippi Governor’s Award for Excellence in Literature and Poetry, and residencies at world-class artist retreats, Fisher-Wirth describes herself as “not an easy writer.” She revises relentlessly, saying she loves it.

“Getting started is the hardest thing of all,” she admits.

She has written with her non-dominant hand to unblock herself, composed pieces backward from the last line to the first, or used prompts like “in that kitchen,” a freewriting exercise she swears by.

“I write a lot of bad stuff,” she says. “Nobody ever sees that. I just hide it away.” However, the labor behind her “visible” poems is a painstakingly rigorous commitment.

Poetry’s Place in Society

What are her goals as the state’s poet laureate?

“Seriously?” she says. “To be able to walk again.”

But Fisher-Wirth hopes to launch several public projects. One is an online series where Mississippians read and reflect on their favorite poems. Another, inspired by New Mexico Poet Laureate Lauren Camp, will gather poems from across the state, written in community workshops and rooted in local experience and place.

She wants to continue her predecessor, Catherine Pierce’s, poetry initiative for schools.

“Poetry isn’t always taught in a way that opens people up,” she says. “Sometimes even great teachers aren’t comfortable with it.” Fisher-Wirth wants to make it more accessible and let poetry breathe in classrooms and communities.

Because for her, poetry isn’t just a luxury of the literary class. It is an ancient mode of knowing. A repository of cultural memory. A form of protest. A balm.

“As communities, poetry is how we pass down our lore. As individuals, it’s how we face being alive. We’re born, we suffer, we rejoice, and we die, and poetry is there for all of it.”

She reminds us that poems were taped to the walls of the 9/11 Memorial. Poems are read aloud at weddings and funerals. Poets bear witness to war or political upheaval.

“Poetry is not about money and power,” she says. “It’s about other ways of finding life meaningful.”

Lines to Carry Us Forward

Certain lines always resonate with Fisher-Wirth, especially now, when the world and her own body are both in a kind of healing.

Wendell Berry, from The Peace of Wild Things:

I come into the peace of wild things

who do not tax their lives with forethought of grief.

Gary Snyder, from For the Children:

stay together

learn the flowers

go light

In closing, she returns to the idea that poetry is a way of saying, in the words of her friend, Joe M. Lamb, in his Facebook photography project, “where the light found me.”

Ann Fisher-Wirth wants Mississippi to help its people find the light and give them the language to hold it.

(The phrase, “where the light found me,” is credited to arborist and poet Joe M. Lamb.)