Efforts to loosen APRN collaborative agreements fall short during 2025 session

- State Rep. Samuel Creekmore said he is considering making adjustments to the legislation before he reintroduces a similar bill next session.

In an effort to address healthcare deserts within Mississippi, the Legislature took up a bill this session that would have changed the state’s medical collaboration requirements for advanced practice registered nurses (APRNs).

However, after the measure passed the House, it died in committee in the Senate.

APRNs include nurse practitioners, certified nurse specialists, nurse midwives, and certified nurse anesthetists.

Mississippi law currently requires medical professionals in these fields to provide respective care under a “collaborative agreement” with a supervising physician. Supervising physicians are required to review 10 percent of an APRNs’ treatment charts within 30 days. The agreements are required to be maintained as long as the APRN is practicing in their respective field.

As previously reported, HB 849, and the subsequent committee substitute HB 1437, aimed to put a time limit on those agreements, ending after 8,000 hours of practice. Those hours would be retroactive for currently practicing ARPNs. Neither bill made it out of the Senate.

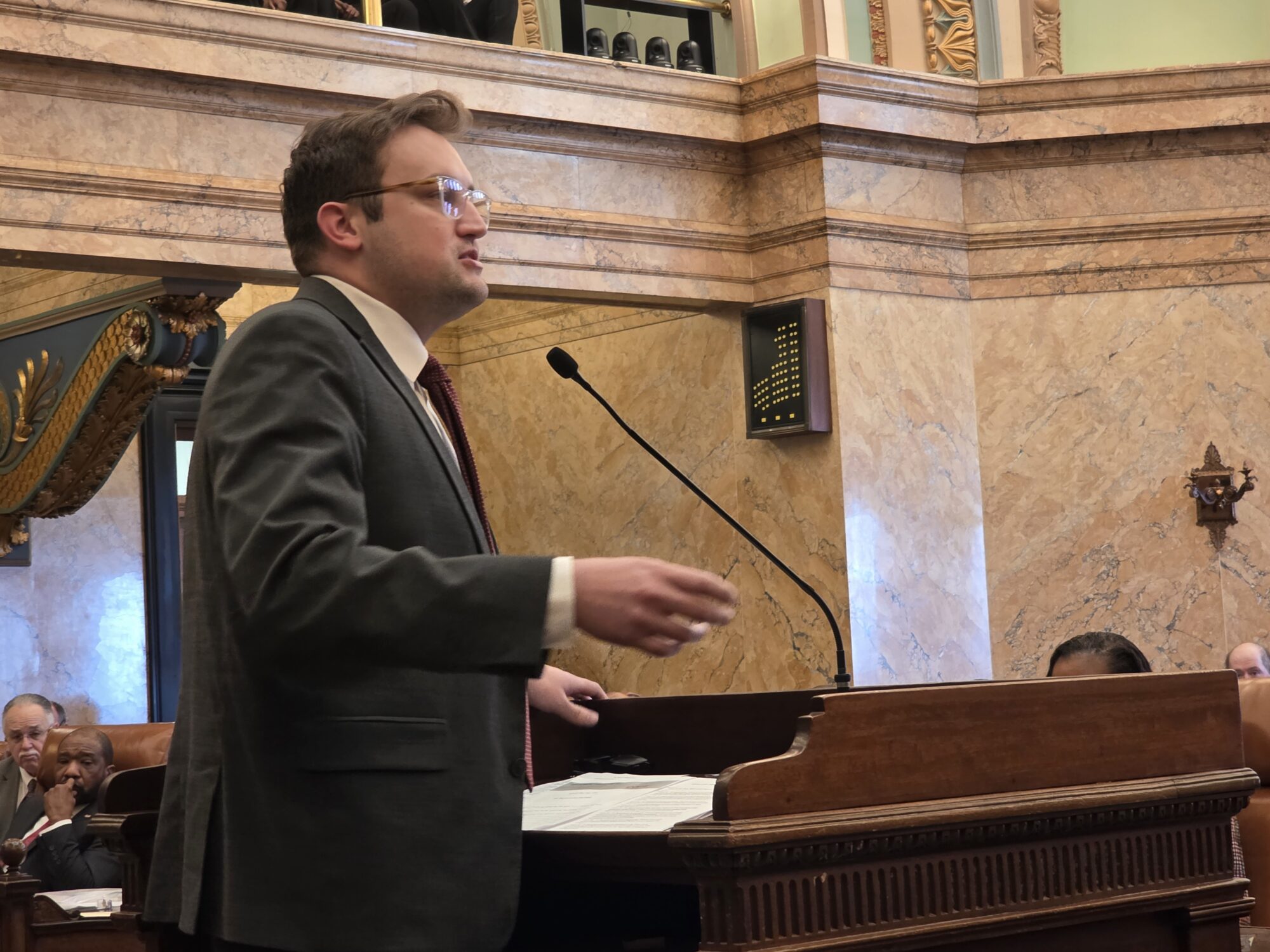

“The Senate really didn’t have the appetite to take it up, especially after so much energy was put into CON (Certificate of Need),” House Public Health Committee Chair Rep. Samuel Creekmore (R) told Magnolia Tribune.

Arguments for and against

State Rep. Creekmore said his intent, as in previous years, was to address the medical care deserts seen in many parts of the state. By loosening those agreements, he said Mississippi would be better positioned to attract more healthcare professionals to stay or move in state to practice.

Currently, there are just over 2,000 general practice physicians working in the Magnolia State, which Creekmore noted is a decline from previous years.

“The nurse practitioners can help fill that void for general practice physicians,” Creekmore added.

Certified Registered Nurse Anesthetists (CRNAs) took center stage during discussion of the bill this session, a need Creekmore said is also in high demand. Within Mississippi there are roughly 250 physician anesthesiologists but more than 900 CRNAs, Sandy Weathers, President of the Mississippi Association of Nurse Anesthetists said.

Not only did Creekmore’s bill find resistance in the Senate, he said physicians expressed their opposition as well.

“They say that physician-led healthcare is the best model for the state,” Creekmore elaborated. “I get that, but you know, the collaboration, to me, the state requires they only collaborate with 10 percent of the cases. So, 90 percent of the patients nurse practitioners see, most of the time there’s no collaboration. So, what are we doing?”

Physicians also argue that the agreements demonstrate to the public there is quality in the healthcare they receive, an argument with which Weathers disagrees.

“Quite frankly, that’s not the fact,” Weathers said. “The bottom line is the collaborative agreements have continued to be a barrier to anesthesia care in our state.”

Dr. Tyler Stout, an anesthesiologist currently practicing at St. Dominic’s, contends that loosening the restrictions on CRNAs will not lead to greater immediate access.

“What problem are you trying to solve if you loosen the regulations?” Stout asked. “There’s no argument we have a deficit of physicians and advanced practice nurses in the state. What I’m arguing is that changing state law, loosening requirements, does not improve patient care and it does not improve access to care.”

The American Medical Association sent a letter to Creekmore in opposition to the legislation. James L. Madara, MD, CEO and Executive Vice President of the AMA, stated that there is a difference in the number of hours of education and training involved to become a physician compared to positions classified under APRN.

“The stark difference in education and training between physicians and advanced practice registered nurses cannot be overstated. Physicians complete 12,000-16,000 hours of standardized clinical training, while nurse practitioners complete just 500-750 hours—less than five percent of physicians training. Likewise, certified registered nurse anesthetists complete just 2,600 hours of formalized clinical training—again a fraction of that completed by physicians,” Madara stated.

Weathers told Magnolia Tribune that the total number of hours required to become a CRNA is a bit higher, ranging from 9,500 to 9,800 hours of training.

“We show that our training is very similar in style and length to the anesthesia training of a physician,” Weathers described. “It’s not exactly, but it’s very similar.”

It is understood that physicians receive more training in order to obtain their position. That is why Stout says if the regulations were changed, there would be no need for someone to put in that amount of time to become an anesthesiologist or physician in other areas of medicine.

“And I would argue the opposite as well. If you loosen this requirement, what happens to the physicians in the state?” Stout continued. “Do physicians want to work in a state that has those requirements, which essentially says that their degree really doesn’t have any more meaning than an advanced practice nurse? If you are for this, are you also for dental hygienists practicing dentistry, are you also for paralegals practicing law, and so on and so forth. What about the licensed practical nurse that’s been working for 10 years? We have a nursing shortage, so should we just make them RNs after a certain number of hours? Like, when does this stop?”

Who’s behind the needle?

During discussion of the bill in the Legislature, an argument was posed that anesthesia procedures are not directly performed by physician anesthesiologists. Weathers said that in Mississippi, more than 75 percent of all anesthesia procedures are directly conducted by a CRNA.

Stout disagrees that CRNAs are essentially working unmonitored.

“I’d love to see that supportive data. In my mind, that is just not accurate,” Stout said.

As an anesthesiologist who has worked at three major hospitals in Mississippi, Stout said there is always a supervising physician on the premises. In his experience, that is typically an anesthesiologist or other supervising physician.

He admits that while the supervising physician is not always an anesthesiologist, about 90 percent of the time in larger hospitals where he has worked, there is an anesthesiologist on-site, and that physician is always involved in the patient’s care before, during and after the procedure. Those physicians, Stout added, work with the CRNAs to form an anesthetic plan of care. However, he concedes he cannot speak for how things operate across the entire state.

“Nurse anesthetists have some really good skills and we’re supportive of them and very appreciative of them,” Stout explains. “But we’re also involved in the pre-op, the inter-op, where they are during the critical part of the procedure.”

Yet, Weathers states that a collaboration requirement does not mean the collaborating physician is typically in the same facility, or the same town when the procedure is performed for that matter. He also takes issue with the requirement that only 10 percent of the cases be reviewed within 30 days, not the day the procedure is being conducted.

“All of this has been defended by the physician anesthesiologists and the Mississippi Medical Association under the guise of safety, and there’s just not any evidence that supports that,” Weathers said. “This truly comes down to economics.”

While the collaborating physician anesthesiologist may not be in the building with their CRNA, Weathers confirmed there is always a supervising physician and/or surgeon in the facility who can lend a hand if an emergency were to arise.

“You’ve probably had anesthesia yourself from a CRNA and thought it was an anesthesiologist,” Weathers said.

Benefits of collaborative agreements

While there are cited negative aspects of the collaborative agreements, medical professionals admit to some benefits in the early days of their medical career.

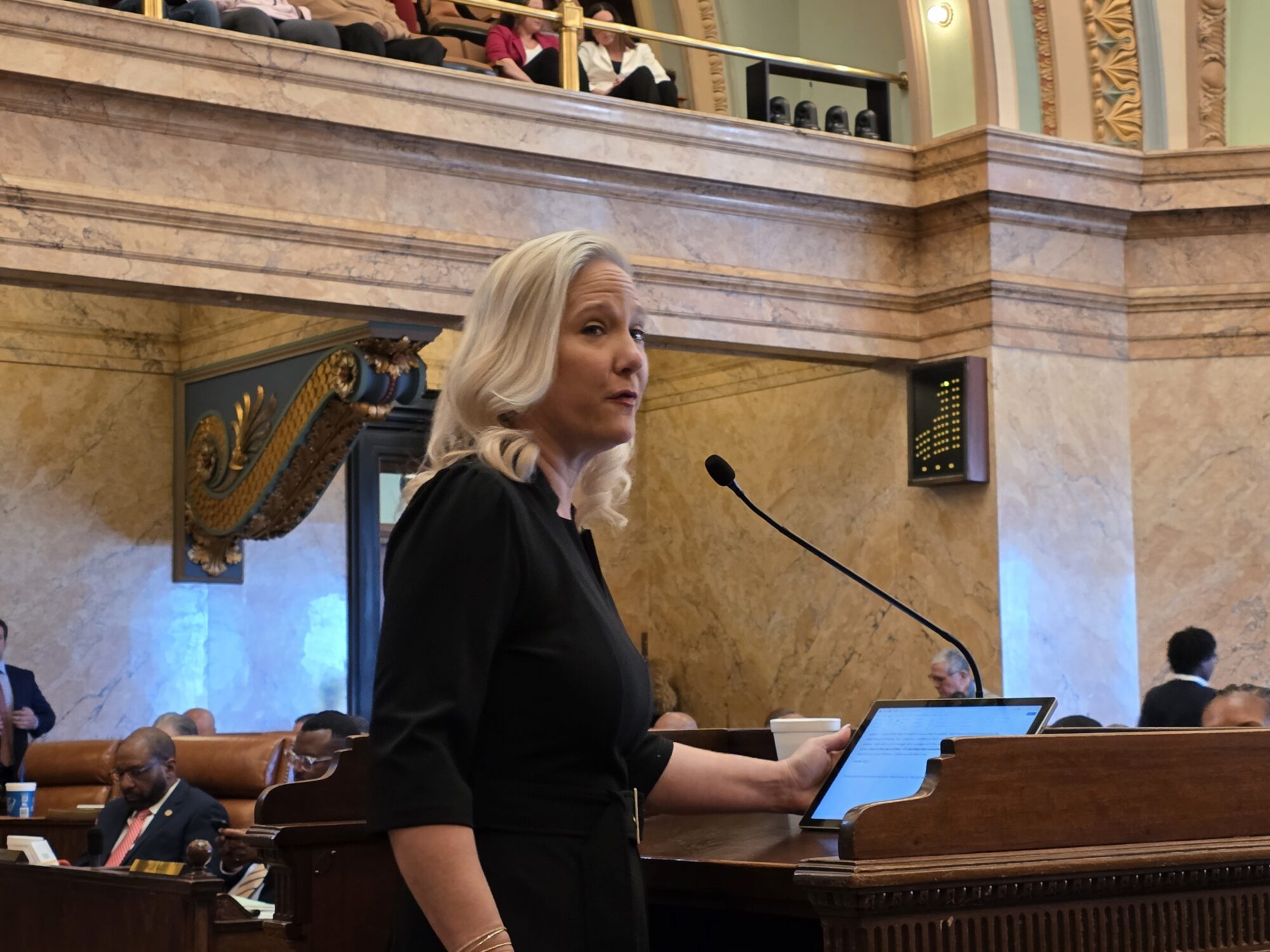

Brittany Clark, a nurse practitioner in New Albany, said her collaboration was more beneficial the first few years of running her clinic. Ten years ago when she opened her clinic, she and the other nurse practitioners on staff made calls regularly to consult with the physician.

“So, in the early years I think it’s very beneficial to have that agreement there,” Clark added.

But as the years went on, those calls dwindled, from weekly or monthly to about 10 per year for the first three or so years into the clinic’s operation.

Clark said she cannot recall a time in the past several years that she had a question for her physician, but she regularly calls other specialist medical professionals in the state with questions.

Those medical professionals do not receive a fee from her like her collaborative physician.

The fee system

Some APRNs must pay their collaborative physician a fee on a monthly basis.

Under current law, Weathers said CRNAs do not typically pay fees directly to the collaborating physician. However, practicing nurse practitioners are required to pay monthly fees to their physician, and some physicians collect those fees from more than one nurse practitioner each month.

Clark said she knows of some physicians who have collaborative agreements with dozens of nurse practitioners across the state.

She pays about $1,500 a month for her clinic’s collaborative agreement.

“Outside of my rent this is the second largest bill that I have at my clinic each month,” Clark added. “And when I think about what I could do with that money, I could hire another nurse. I could implement chronic care management systems. I could get an X-ray machine, which would take away several of the ER visits we have to send out.”

Next steps next session

Rep. Creekmore said he is considering making adjustments to the legislation before he reintroduces a similar bill next session.

One change will be to carry over the requirement to increase the number of spots in the Rural Doctor Program from 62 to 100. That was added as an amendment to HB 849 by State Rep. Bryant Clark (D) during the 2025 session.

The other change will be to ensure those spots are directed to areas that truly are healthcare deserts to aid in overcoming recruitment hurdles.

“Not everyone wants to move their families to some of these areas where not only is the healthcare insufficient, but so are the school systems and just the economic status of that area is on the decline,” Creekmore described. “Because right now in the rural physician program a doctor can end up in Tupelo or New Albany, which are pretty strong healthcare communities already. So, the Rural Physician Program is not necessarily addressing rural deficient areas like it should be.”

Weathers agrees with Creekmore that lessening the regulations will help with recruitment.

“Because if they can go across state lines and have less restriction and practice more freely and utilize the tools that their education has provided them, these professionals are going to do that,” Weathers added.

As attempts at passing such legislation continues, so too will the opposition advocating to keep the regulations in place.

“The AMA has and will continue to stand firmly with patients who have said repeatedly that they want and expect physicians to lead their health care team; 95 percent of U.S. voters say it is important for a physician to be involved in their diagnosis and treatment decisions. Notably, 63 percent of voters specifically oppose allowing nurse anesthetists to perform anesthesia without physician oversight – a dangerous change that these bills would permit,” AMA CEO Dr. Madara stated in his letter to Creekmore.

While loosening the regulations may lead to more practitioners, Stout argues making such a change will not be best for patient care and doubts it will be an effective recruitment tool.

“I don’t think we’re going to have this massive influx of mid-level providers that go, ‘Man, let’s go to Mississippi,'” Stout said.