Ward is the only woman and the only African American who has won two National Book Awards for Fiction.

“I am not worthy,” said Jesmyn Ward near the end of her author event with Margaret McMullan at Millsaps College in early November.

Not worthy? The author—the only woman and the only African American—who has won two National Book Awards for Fiction? The writer who appeared onstage in a fittingly bright orange skirt and spoke animatedly and with incessant gesticulation?

“I will struggle with this the rest of my life,” Ward affirmed. Then she looked back to herself in elementary school. “I never spoke in class. I suffered impostor’s syndrome. I’m an introverted person. It’s painful for me to speak; I am afraid to say it aloud.”

But as she continued education endeavors, becoming the first in her family to attend college, a professor finally “pulled it out of me,” and she discovered “I had something to say!”

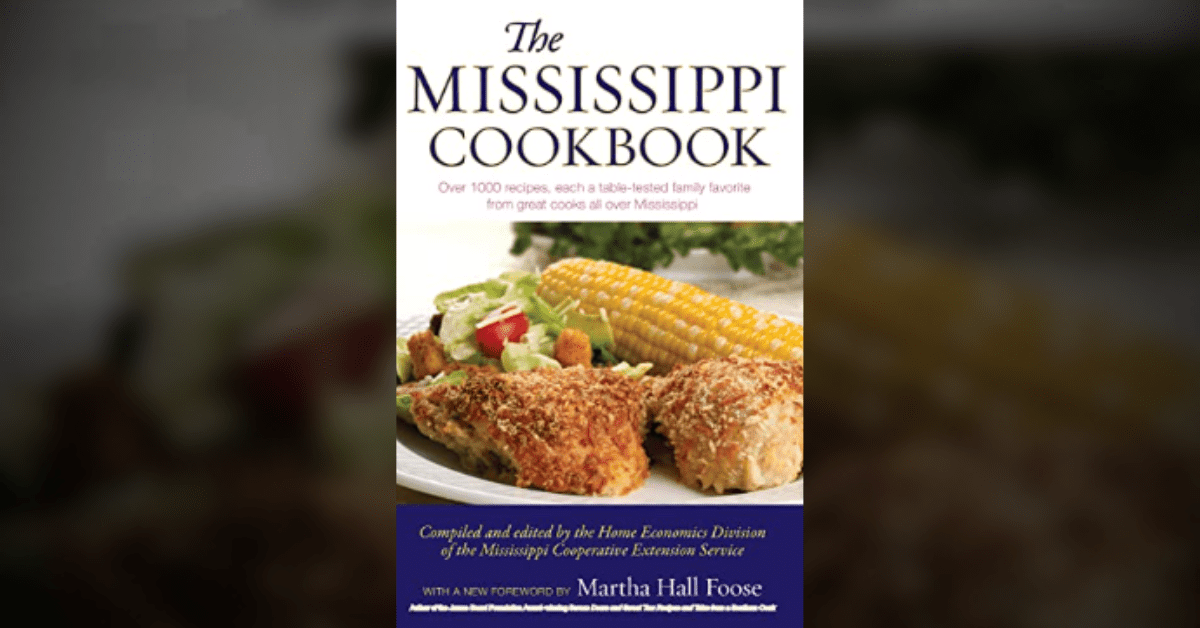

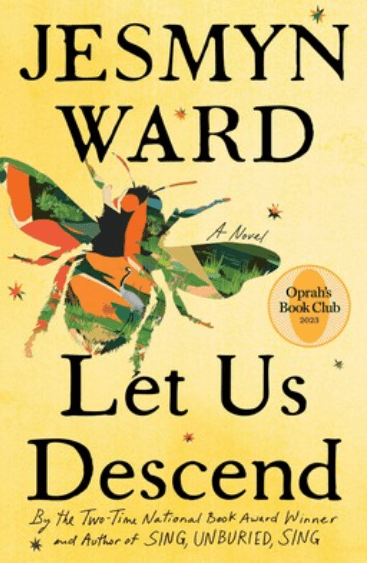

For her latest – her fourth – novel, Let Us Descend, Ward researched American slavery for two-and-a-half years. The concept came from a short radio piece she heard in 2015 while driving from her home in Mississippi to her job at Tulane University in New Orleans. She recalls the historian on the radio talked about the role New Orleans played in America’s domestic slave trade, how the city had dozens of slave pens. She knew of only two, and “one of those was in the wrong location.”

Born in Berkeley, California, as a three-year-old she moved with her parents to their place of origin: DeLisle, Mississippi, just north of Pass Christian and south of I-10. After they divorced, her father moved to New Orleans, where she spent much of her adolescence with him and his family. But she knew nothing of the Crescent City’s having been the capital of the domestic slave trade in the early 1800s.

“What we learned in school,” she said, fails to tell the whole story. She knows that over time, slave revolts occurred about every twenty years or so, that people ran away and tried to establish self-sufficient communities. Some who remained tried to reach out and support the runaways. Some survived through resistance. But the radio piece stirred her curiosity.

What she learned during that research phase led to two-and-a-half years of writing—a time she uses as an opportunity to discover what she is writing about. “Trying to figure it out…well, maybe… But…”

As she writes, the characters “take on life. I know nothing about them. They do things that surprise me. Annis is not a victim, and she is not only a survivor—not flat; she is complicated, complex. And while I channel my characters, I also am pulling on my own experience to try to understand them.”

Unlike many authors, Ward uses no outline, but she does frame her writing space with images that inspire her for topics she is curious about: photos, poems, notes that inform the texture, the rhythm, the impact of every word she writes. Showcasing her major works, Amazon lists thirty-five titles for the prolific writer.

The Kirkus review of Let Us Descend affirms that “Ward may not tell you anything new about slavery, but her language is saturated with terror and enchantment … she makes the unimaginable horror, soul-crushing drudgery, and haphazard cruelties of the distant past vivid to her readers.”

Publisher Simon & Schuster describes the novel as “a reimagining of American slavery, as beautifully rendered as it is heart-wrenching. Searching, harrowing, replete with transcendent love, the novel is a journey from the rice fields of the Carolinas to the slave markets of New Orleans and into the fearsome heart of a Louisiana sugar plantation.” Through her journey, the heroine Annis “opens herself to a world beyond this world, one teeming with spirits … turns inward, seeking comfort from memories of her mother and stories of her African warrior grandmother.”

Ward admits she has “always loved women warriors” and that almost all her work showcases warrior women. She herself has had to draw strength from such women. After earning a BA degree in English and an MA degree in media studies at Standford University, she became a writer to honor the memory of her younger brother, killed by a drunk driver in 2000. She went back to school, to earn an MFA degree in creative writing from the University of Michigan. And then, Katrina.

Publication of her first work took time, almost compelling Ward to give up writing and enroll in a nursing program. But Agate Publishing accepted Where the Line Bleeds, and Essence magazine picked it as a book selection. Its garnering several prestigious awards encouraged Salvage the Bones, given the National Book Award for Fiction in 2011 plus other honors, and Sing, Unburied, Sing, her second National Book Award for Fiction winner in 2017.

Her Tulane profile reveals that from 2008-2010, Ward had a Stegner Fellowship at Stanford University. She was the John and Renée Grisham Writer in Residence at the University of Mississippi for the 2010-2011 academic year. In 2016, the American Academy of Arts and Letters selected her for the Strauss Living Award. She received the prestigious MacArthur Fellows “Genius Grant” from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation in 2017.

Ward’s nonfiction titles also draw praise. Published in 2013, Men We Reaped explores the lives of her brother, Joshua Adam Dedeaux, “who leads while I follow”—and four other young black men who died in her hometown. The Fire This Time: A New Generation Speaks about Race, launched in 2017, features groundbreaking essays and poems about race that she collected and edited; it also became a New York Times bestseller.

From her 2018 commencement speech at Tulane, Simon & Schuster published Ward’s Navigate Your Stars, proclaimed “a meditation on dedication, hard work, and the power of perseverance.”

That power wavered in 2020 after her partner, Brandon R. Miller, the father of her two children, died suddenly in January of acute respiratory distress syndrome. The whole family had seen their family doctor, she and the children being diagnosed with flu but her husband “inconclusive.”

“I sank into hot, wordless grief,” she wrote for Vanity Fair. And at Millsaps, she admitted that grief left her “stuck. I did not write. I just stopped. But in July, I realized I had stopped and talked to myself. I asked, ‘Are you done?’ It hurt, and I felt very said. It felt wrong, painful. But the last thing he would want was for his leaving to leave me silent; so, I recommitted myself to the Work.”

Dealing with her own deep grief, Ward wrote about Annis, another woman “even more intimately acquainted with grief than I am, an enslaved woman whose mother is stolen from her and sold south to New Orleans, whose lover is stolen from her and sold south, who herself is sold south and descends into the hell of chattel slavery in the mid-1800s.”

In the three-and-a-half years since her partner’s death, Ward has persevered. For one interview, she revealed her knowledge from her brother’s death that she would endure at least two years of grief, that she would have to remake herself. So, she struggled. Now she and a new partner share the caring of her youngest child, and she leans with a new lightness into her current book tour.

Her publisher describes Let Us Descend as her “most magnificent novel yet, a masterwork for the ages.” Ward dedicated the book to “Brandon, who saw me and loved me, even when I could not see or love myself, and for Joshua, the first to show me that love is a living link to the dead.”