Over the next few weeks, Y’all Politics will be sharing interviews and articles related to the passage of tort reform that occurred 20 years ago in the longest special session in Mississippi history.

Y’all Politics will be talking with key players from that 2002 special session and the years to follow, outlining tort reform’s impact on both the legal community and Mississippi politics in this series we are calling “Jackpot Justice +20.”

Twenty years ago today, over breakfast, then-Governor Ronnie Musgrove told a group of trial lawyers who had long supported his campaigns and the campaigns of his fellow Mississippi Democrats that he would convene a special session of the Legislature to enact tort reform. The pressure to do so, Musgrove would later say, was just too great.

What would then transpire, despite the objections voiced in the room that morning, changed the face of Mississippi politics, and perhaps the legal community, more than any other single action ever taken by the Legislature.

Over the years, trial lawyers had been able to rake in millions of dollars in settlements from using the court system in innovative ways in personal injury cases against hospitals, industries and businesses of all sizes. Personal injury and mass tort was big business, so much so the state was known across America for its “jackpot justice.”

A number of these trial lawyers became unimaginably rich, politically powerful, and nationally famous – some even infamous – over the years, names like Dickie Scruggs, Joey Langston, and Paul Minor. Nearly all trial lawyers at the time fundraised and gave generously to Democrats and Democratic Party causes across Mississippi, effectively peddling their influence at the state and local levels to keep the state favorably blue while increasing their bottom-line with relative ease. Being a trial lawyer became synonymous with being a Democrat.

Yet, the times were changing. Following big payouts from asbestos cases in the late 1980s and early 1990s and product liability lobbying from the tobacco industry in 1992 and 1993, the Mississippi Legislature took up a version of tort reform that addressed personal injury laws, but the 1993 legislation failed to cap jury awards to a plaintiff. At the time, it was heralded as a compromise between the business and the legal special interests.

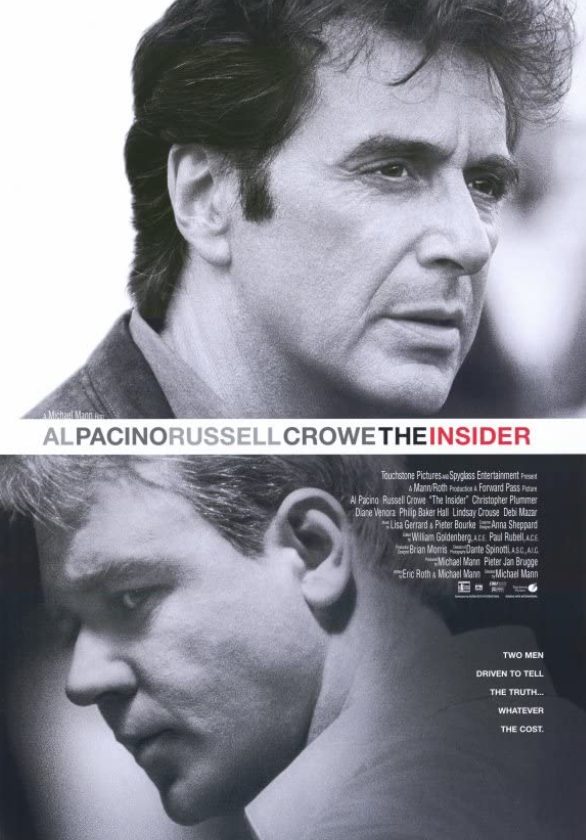

However, trial lawyers continued to manipulate the system and capitalize on loose Mississippi laws, giving them even more high dollar wins and large multimillion dollar payouts. Perhaps the most well-known of these cases was the Big Tobacco case that even became a Hollywood movie featuring Al Pacino and Russell Crowe in 1999. These courtroom wins enabled the trial lawyers to continue to fund sympathetic Democrats across the state, chief among them were former Attorney General Mike Moore and Musgrove.

Musgrove was to be the trial lawyers’ friend in the Governor’s Mansion. An attorney himself, Musgrove had been a state senator and then Lieutenant Governor. His 1999 election for Governor was the closest election in Mississippi history as neither he nor Republican Mike Parker won a majority of the popular vote. State law mandated, at the time, that the final decision be made by the House of Representatives. The Democratic majority in the House, backed in large measure by the trial lawyers’ political action committee, swiftly put forward Musgrove and his trial lawyer donors celebrated.

So, when Musgrove called his trial lawyer pals in on that August 23, 2002, morning, a little over a year before the next statewide election, to tell them of his decision to call a special session to take up tort reform in a more substantive manner than tried a decade earlier, the trial lawyers could not believe the Democrat Governor they had backed would give in and upset their political machine.

But Musgrove was right. The political headwinds had gotten too strong not to take up the legislation. Mississippi’s medical and business environment was viewed as the most hostile in the nation when being sued. Investors were wary of setting up shop in Mississippi. Doctors were refusing to treat trial lawyers and their families. Hospitals feared losing their staffs and having to close facilities or reduce service. Business owners were up in arms in every part of the state, worrying if a fall by a customer would mean they would lose their livelihoods. Even former President George W. Bush spoke on the need for tort reform in the state on a visit that 2002 summer.

What ensued when Governor Musgrove called in lawmakers was an eighty-three-day special session, the longest in state history, that produced a more stable business and medical climate in the state that settled fears. It also permanently undermined the primary source of funding for Democrats in Mississippi by restricting large payouts for trial lawyers, the main contributors to the Democratic Party, and solidified Republican support within the business community, support that continues to this day.

That does not mean Musgrove, for his part, did not try his best to capture business support and put on a good face following the vote. He did. Upon signing the bill into law, he was quoted in the L.A. Times as saying, “What we have signed is something that will give a fair, level playing field to our system in Mississippi… A message has been sent to the rest of the world about doing business in Mississippi. This is a good place to do business.”

But it was not enough, and the trial lawyers and his Democrat base were not buying it.

“Reform is a misnomer,” David Baria, the president of the Mississippi Trial Lawyers Association and eventual Democratic state senator and representative told the L.A. Times following tort reform’s passage. “To cap punitive damages is to say to corporate America that they can injure or kill people and be held less accountable than in the majority of states in this country.”

Baria went on to say that the Legislature spoke and told citizens that, “It’s more important to make Mississippi business-friendly than to make it a place where businesses are accountable.”

Truth be told, that fateful breakfast meeting called by Musgrove was the beginning of the end for the Mississippi Democratic Party. The result of tort reform’s passing would be more election losses by Mississippi Democrats to Republicans in 2003 than in any cycle since Reconstruction. Twenty years later, Democrats still have not recovered.

In 2003, a native son of Yazoo City who had made a name for himself in national Republican politics would return home to challenge Musgrove for Governor. Even though a tort reform package had passed the Legislature that Fall of 2002, Haley Barbour made it a primary theme in his 2003 campaign, saying the state needed to go further to protect doctors, hospitals, businesses and industries. That message continued to resonate with voters.

Mississippi voters now permanently linked trial lawyers with Democrats, in a similar manner as they do labor unions and teacher unions. The messaging stuck. Musgrove, the Democrat incumbent who had called that 2002 special session, saw no political upside from tort reform’s passage; if anything, Democrats walked away from him. Barbour would beat Musgrove handily in November 2003, winning 53% to 46%, setting up a twenty-year run for Republicans as the state’s chief executive.

Barbour, the new Republican Governor, would be sworn-in in January 2004 and just months later call a special session of his own to pass another round of tort reform legislation, further solidifying the end of trial lawyers’ hold on both the legal system and Mississippi politics.

###

Y’all Politics will be sharing a conversation with authors Andy Taggart and Jere Nash who wrote “Mississippi Politics: The Struggle for Power, 1976-2006,” which a large part of this article is based on with their permission. You can find the Second Edition of their book for purchase on Amazon here.