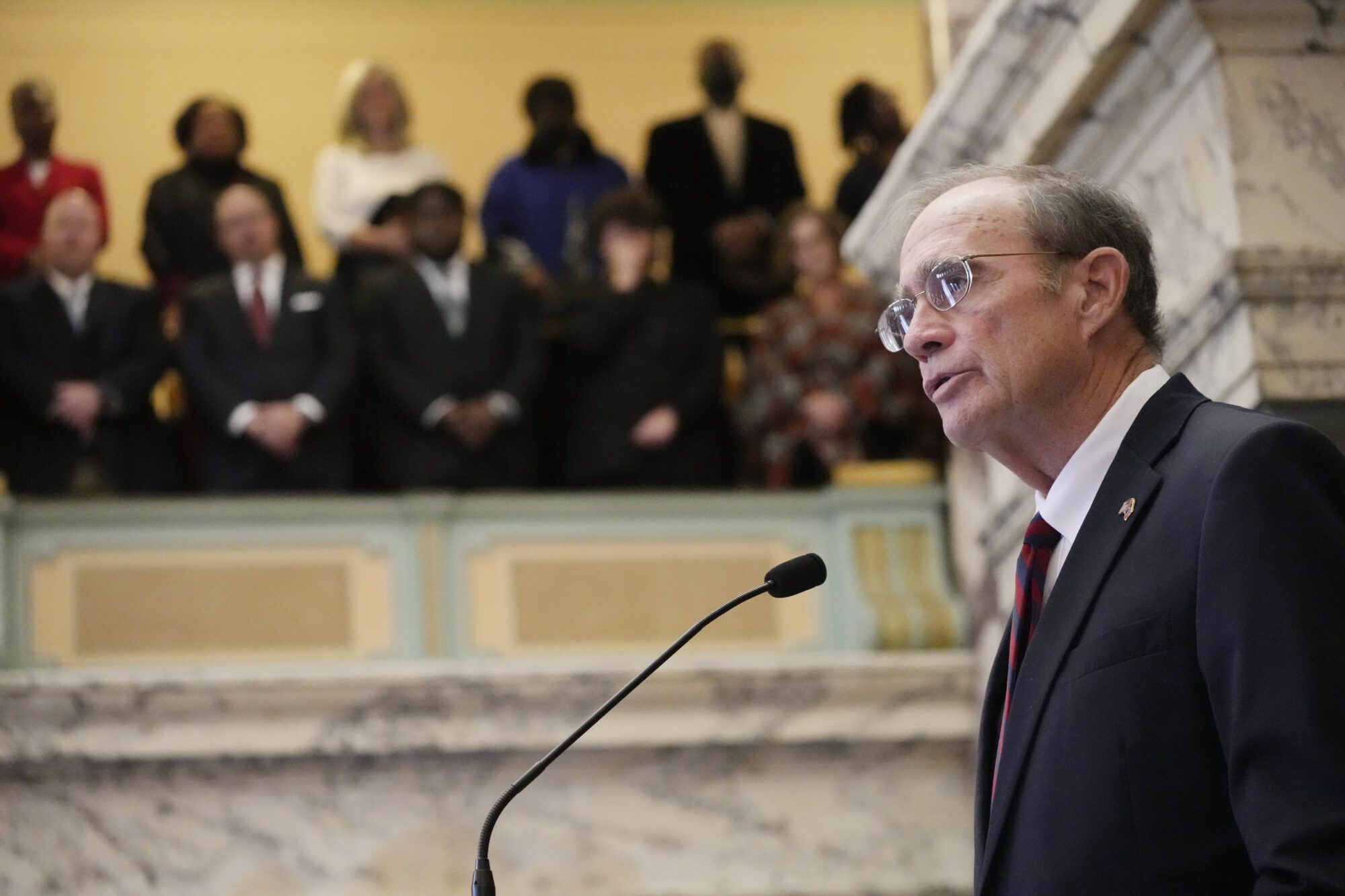

Sid Salter

- Columnist Sid Salter says let’s not lose sight of the significance of the structural tax changes the tax reform legislation passed last week could provide if signed into law.

While the typos in the tax compromise legislation sent from the State Senate to the State House of Representatives last week are garnering most of the attention from politicos, insiders and those who oppose aspects of the bill, let’s not lose sight of the significance of the structural tax changes the legislation could provide if signed into law.

The legislation provides a path to eliminating the state’s income tax. However, the typos in the bill deal with a core component—the speed with which income tax reduction or elimination can or should be accomplished.

But the compromise extends to other taxes as well, including the sales tax on groceries.

Sales taxes account for about 38.4% of state tax revenues. It is essential to reflect on how that tax originated. The Great Flood of 1927 fundamentally transformed the state’s economy, which was on the brink of another economic disaster—the Great Depression. Agriculture struggled to recover after the 1927 flood, so the Great Depression dealt a second blow to Mississippi’s troubled economy.

History recounts that at the beginning of 1932, the State of Mississippi had a whopping $,1,327.00 in the state treasury with accounts payable of nearly $6 million. Many Mississippi school teachers had not been paid in over a year and the pensions of the state’s Confederate Veterans were likewise unpaid.

Mississippi began 1932 with some $50 million in debt. In April 1932, one-fourth of the state’s agricultural lands – family farms – were sold for taxes. Tax sales held in 74 of the state’s 82 counties claimed roughly 400,000 acres on 40,000 farms from plantations to small acre homeplaces.

In that 1932 fiscal maelstrom, Mississippi Gov. Mike Conner proposed the nation’s first sales tax at three cents on the dollar. The Legislature gave him a two-cent tax that has since grown to a 7% sales tax.

Last week’s tax compromise offers a 2% reduction in the state’s sales tax on groceries. All sales taxes are regressive – penalizing the poor more than the wealthy – but after more than a quarter-century of political infighting, the proposed compromise offers some relief.

After the inflation endured on groceries during the Biden Administration and that promised by rising tariffs in the Trump Administration, any relief on grocery bills will be welcomed by Mississippi shoppers.

Mississippi’s individual income tax accounts for just over 30% of state tax revenues while the state’s property taxes primarily support local government sources.

Another intriguing facet of the tax compromise is an increase in the state’s gasoline tax. The tax compromise calls for adding a total of nine cents per gallon (CPG) to the state’s gas tax over the next three years. The only state with lower gas taxes than Mississippi is Alaska.

Mississippi’s current 18.4 cents per gallon state gas tax (CPG) is a flat tax. When we paid $3.965 a gallon for gas in 2008, the tax was 18.4 CPG. When we pay $2.42 per gallon at the pump this week, the state tax is still 18.4 CPG.

The only way the state takes in more revenue in gas taxes is for the volume of gas consumed to increase – and automobiles are now manufactured to require less fuel consumption than a decade ago. The state fuel tax rates haven’t increased since 1987, the last time the state was particularly serious about improving our highway system.

The federal fuel tax is also 18.4 cents per gallon and hasn’t changed since 1993. Neither the federal nor state fuel taxes have kept pace with inflation. Indexed for inflation, both federal and state fuel tax rates are insufficient to adequately build and maintain those infrastructures – but this increase will be a dramatic improvement in Mississippi over time.

The bill creates a fifth tier in the state’s Public Employees Retirement System for newly hired state employees after March 1, 2026. In that plan, 4% of their retirement savings would be placed in a defined benefit plan and 5% would go to a defined contribution plan, similar to a traditional 401K. The legislation also eliminates the Special Legislative Retirement Program, or SLRP, for legislators elected after March 1, 2026.

Decimals aside, there are a lot of needed reforms in this legislation that also accomplish the original intent of reducing and eventually eliminating the income tax. To be sure, the decimal placement matters but that can be fixed without throwing the proverbial baby out with the bath water.