Photo from vicksburgradio.com

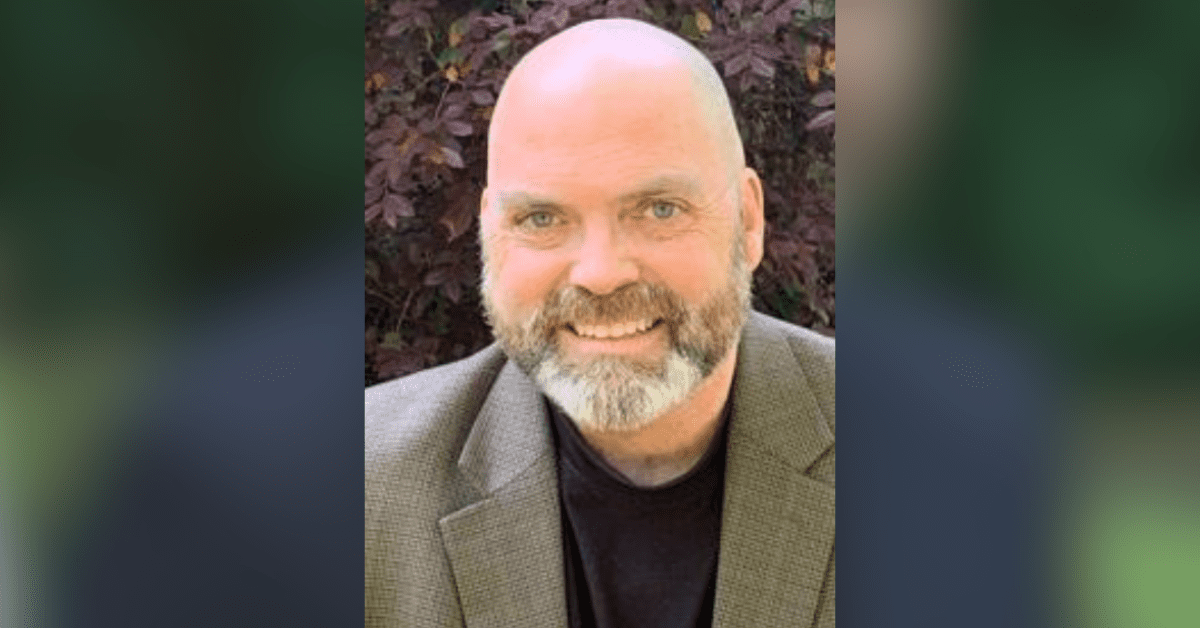

- Tommy Couch and Wolf Stephenson, like the many Mississippians they have recorded and produced since 1967, aren’t just music makers; they’re culture makers – prime examples of one of the things Mississippi and its capital city do best.

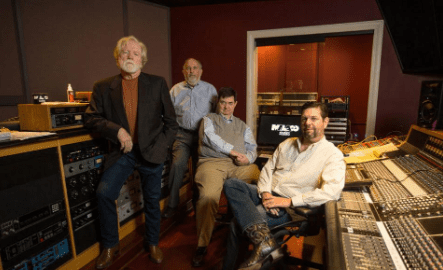

Shortly before West Northside Drive runs into Medgar Evers Blvd in Jackson, Mississippi, sits a collection of unassuming brick buildings with a Mississippi Blues Trail historical marker out front.

Malaco Studios may not be one of Jackon’s most recognizable architectural landmarks, but it is a cultural bulwark of the capital city, and by extension Mississippi itself. Malaco’s slogan, “The Last Soul Company,” rings true now more than ever in this regard, with a historically outsized cultural influence that is hard to overestimate. Tucked away in West Jackson, the studio has recorded and produced countless southern pop, R&B, and gospel icons. Malaco has even played host to the likes of Paul Simon as well as legendary session musicians from Muscle Shoals and the Atlanta Rhythm Section.

Made in Mississippi

What we now know as Malaco Records began in the early 1960s when Tommy Couch Sr. and Gerald “Wolf” Stephenson started booking bands for fraternities at the University of Mississippi. Couch still serves as Malaco’s board chairman. His son, Tommy Couch Jr., serves as president. Stephenson is vice president of the company.

“[We were] both in the same fraternity and both in the same school of study, which, strangely enough, was pharmacy. Both of us graduated with a degree in pharmacy,” said Stephenson. “He was in Jackson already when I graduated, and by chance, strictly, I got a job in Jackson. So the first thing Tommy said to me when I moved to Jackson was, ‘I want to open a recording studio in Jackson, Mississippi.’ And I kind of thought, ‘Are you crazy?’”

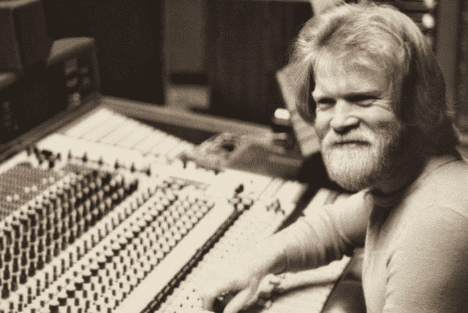

Couch set up shop in Jackson to continue booking bands and promoting concerts alongside brother-in-law Mitchell Malouf. “He talked me into helping him,” said Stephenson, who had worked as an electrician during college. “The equipment came in and I helped him hook that up. We cranked it up and started kind of fooling around with it. After two or three weeks of that, I said, “You know what? This might be more fun than counting pills.”

In 1967, they began experimenting with local artists to produce master recordings at the location that Malaco calls home to this day. The studio enjoyed limited commercial success at first: “When we first opened, we would rent studio time to anybody that would show up.”

It was not a booming business by any stretch of the imagination. That is, until Atlantic Records picked up an album by King Floyd from Malaco’s Chimneyville label. New Orleans jazz and R&B producer-arranger Wardell Quezergue had brought Floyd to Malaco for sessions that yielded the smash-hit “Groove Me.”

“The first hits that we ever had—really substantial hits—were due to Wardell,” Stephenson remembers. By the early-to-mid 70s, the “Malaco touch” was in high demand. Atlantic even sent the Pointer Sisters for a few sessions. Paul Simon visited to record parts of There Goes Rhymin’ Simon in 1973. The song “Learn How to Fall” from that album was cut in its entirety at Malaco. Malaco also released its first gospel record later that year.

After another dry spell in 1974, Malouf left the company. Couch and Stephenson needed a breakthrough. “We were getting a little slim,” Stephenson said. “So Tommy and I were taking turns skipping paychecks.”

But the pair unknowingly had an ace up their sleeve: “One of the best singers I ever worked with was from Jackson: Dorothy Moore.”

Moore had recorded “Misty Blue” at Malaco in 1973, and rejection slips had piled up after attempts to shop the master to big record labels, so it sat on a shelf for almost two years. Couch and Stephenson called an audible and released “Misty Blue” on their own label just before Thanksgiving in 1975. It became an overnight sensation, making it almost to the top of pop and R&B charts in the U.S. and the U.K.

Malaco targeted the gospel market again that year by signing a Jackson-based black gospel group called The Jackson Southernaires. Several other premium gospel artists subsequently signed on.

Throughout the late 70s as Couch and Stephenson tried to make ends meet at Malaco, Stewart Madison, who was acquainted with the duo at Ole Miss, was facing similar problems at Sound City Recording in Shreveport, Louisiana. The operations spent countless hours on the phone with one another during the “lean years.” They also made frequent visits to each other’s facilities, searching for a plan of action that would keep the lights on in Jackson and Shreveport.

Eventually, Madison sold Sound City Recording and joined forces with Malaco, stepping in as the company’s business manager. He remains in that role today.

Stayed in Mississippi

Stephenson attributes much of Malaco’s success to the coinciding success of the 1970s rock-and-roll model: “The major labels, all of a sudden, their accounting departments had started calling their attention to the fact that with these big rock groups, you can sell 10 million albums rather than 200,000 or 300,000 singles.”

When soul and blues artists were literally being kicked to the curb by larger record labels, Malaco gave them a chance and filled the gap in the market. Along came Little Milton, Johnny Taylor, Bobby Bland, and more. “It was really a treat for me to work with them,” Stephenson recalled. “Both Tommy and I grew up just loving that kind of music.”

Malaco had also made forays into the disco scene. The most successful bid was to provide the studio, session musicians, and other personnel for a former schoolteacher and Rust College alumna named Anita Ward. Ward’s 1979 single “Ring My Bell” from the album Songs of Love would reach number one in the U.S., Canada, and the U.K.

Malaco was well on its way to becoming the premier southern R&B and gospel label in the country, and it arguably remains so today. This legacy was threatened, however, in April 2011, when a tornado swept through West Jackson, damaging the studio beyond repair and completely demolishing an office building.

“Luckily for us,” said Stephenson, “we had built a tape vault some years before that. And the guy that built it for us was insisting that if you’re going to build this tape vault to store your tapes in, then you ought to build it where it’s tornado proof, because that’s where your value is: in the masters.”

Needless to say, the vault survived the storm. While Malaco was without a studio, its recording was done at the Muscle Shoals Sound Studio in Alabama, which Malaco had purchased in 1985.

Alabama connections notwithstanding, the company’s Mississippi roots are indelible. From its beginning, many of Malaco’s artists have been local. While most of them never made it “big time,” they were more than enough to keep the studio in business while attracting attention from local radio stations, especially those that were known for playing music by Black artists: “[They] were very, very ready to play local music. If we put out something that was decent, they would play it.”

Stephenson recounts how the mutually supportive attitude among the Jackson music community made all the difference. “There was not a big competition between artists—they all wanted to work for the good of everybody, and that really helped. They were pulling for the other artists in town just as much as they were for themselves.”

They all wanted to work for the good of everybody. There’s something of the indomitable spirit of Mississippi that Malaco has managed to capture.

If you’re driving into Mississippi on any number of highways, you might find a welcome sign that reads, “Birthplace of America’s Music.” In fact, music has always brought Mississippians together. Perhaps nowhere is this more true than in this oft-overlooked corner of West Jackson. Couch and Stephenson, like the many Mississippians they have recorded and produced since 1967, aren’t just music makers. They’re culture makers—prime examples of one of the things Mississippi and its capital city do best.