Author NK Wessman shares the voices of those who owned the responsibility for managing through Hurricane Katrina, those who get paid to stay behind to protect and serve.

Katrina—not my storm, not my job.

As the storm we now know as Hurricane Katrina developed off the west coast of Africa grew from a tropical depression over the southeastern Bahamas, built across the Atlantic, plowed over extreme south Florida, grew stronger over the hot and fairly shallow Gulf of Mexico, and then hammered the Mississippi Gulf Coast, I watched and worried. For the first time in a quarter-century, I was not responsible for preparedness or response communications. I had retired from state service, no longer responsible for getting the word out before the storm and communicating important public health messages afterward.

For the first time in twenty-five years, my only job was to assure personal security for my family, not to help manage population-based preparedness, not even to report as a journalist and public relations practitioner. As communications director for the Mississippi State Department of Health, I had been duty-bound to warn people about the danger hurricanes bring, the harm they can inflict, the debris and hazards they leave behind. What should individuals do to get ready? Should they move to a place beyond the storm’s direct path? How could they deal with lost water pressure, thawed food, cuts and scrapes? Where could they get emergency medical care? My job required that I answer those questions, and on the response team I helped return the community to better, safer, healthier through ensuring people had access to information and connections to disaster recovery assistance.

The National Weather Service labels Katrina “A Killer Hurricane Our Country Will Never Forget.” The costliest hurricane to ever hit the United States and one of the five deadliest hurricanes to ever strike the United States, the bitch storm was responsible for 1,833 fatalities and approximately $108 billion in damage (un-adjusted 2005 dollars).

New York Times bestselling author Douglas Brinkley devoted to Mississippi a chapter of his book The Great Deluge: Hurricane Katrina, New Orleans, and the Mississippi Gulf Coast, released in early 2006. He called the storm a history-altering natural disaster and wrote in introductory notes: “My hope is that this history, fast out of the gates, may serve as an opening effort in Katrina scholarship, with hundreds of other popular books and scholarly articles following suit. Only by remembering, and holding city, state, and federal government officials responsible for their actions, can a true Gulf South rebuild commence in the appropriate fashion.”

Brinkley’s confidence challenged me, especially when the calendar changed to 2008 and I realized that nobody had told Mississippi’s story, not really.

What really happened before, during, and after landfall to the people who owned the responsibility for managing the storm? Who were they, and how did they survive? The people who get paid to stay behind, the individuals who work to protect and serve through the local offices of government and related organizations—were they ready for what hurricane watchers predicted, “the next Camille?”

Phil Hearn wrote about Camille in his Monster Storm. But the real mother of all monster storms struck August 29, 2005.

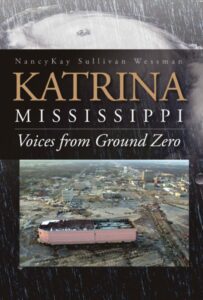

When I published my book, Katrina, Mississippi: Voices from Ground Zero, ten years after the storm, I knew their stories still bothered many first responders, the individuals whose jobs then centered on protecting and serving the 190,000 citizens of Harrison County and some 46,000 who called Hancock County home.

Before Katrina hit, roughly 200 women and men hunkered in the Harrison County Emergency Operations Center (EOC) within the County Courthouse in Gulfport. Only thirty-five stayed in Hancock’s EOC in Bay Saint Louis. They voluntarily stayed in that bunker and in that repurposed bowling alley because they owned the responsibility for managing the unthinkable.

My Katrina work began after the search and rescue, after the response, and well into the recovery and initial rebuilding phase.

I first saw the infinite void Katrina left—miles and miles of emptiness westward from Highway 49 in Gulfport to the Bay of Saint Louis and beyond—in January 2007. I went to the Coast as a freelance reporter for Mississippi Medical News, to cover a meeting of the State Board of Health. Most of the debris had been removed; nothing looked as it had before the storm. Even ten years later, nothing looked the same: landmarks were gone, constructions that resemble bombed-out buildings in the world’s war zones remained in a few places, and new facades over structures that miraculously kept their foundations and at least some of their bone structure.

Even the faces of the folks in charge for emergency management in 2005 compared to those responsible in 2015 had changed. Some simply moved on to other jobs or went back to their pre-storm responsibilities; several retired, others passed away.

But many who shouldered responsibilities within the Emergency Operations Center, and outsiders who worked their way inside to help in the aftermath of Katrina, shared their stories with me. Through one-on-one interviews, opening their files, loaning their videos, referencing their materials—the characters had been waiting for the opportunity to tell their stories. They remained shell-shocked; some admitted post-traumatic shock; and they needed to talk, to find answers, to validate themselves.

I was compelled to write their stories about the public health impact of both the natural disaster and the unnatural consequences that emerged through human efforts. Those “champions of the storm” and I believed that their perspective and actions could bridge to whatever might become the United States’ and the Gulf Coast’s next Katrina. So far as I could discover in 2015 and now, my book is the only story told from inside the emergency operations centers of a major natural disaster.

The book reveals personal recollections of health and medical aspects, special needs victims and mass care through sheltering, pop-up medical clinics, and the sole hospital that withstood the storm and continued providing services. The book introduces characters who addressed issues related to food and water, sewers, volunteers, donations, and other emergency support functions.

Readers learn of catastrophe and courage through the experiences of a public health physician, Robert Travnicek, MD, in upheaval not of his own making but caught in a quagmire of natural disaster, local and state politics, and moral determination. EOC Commander General Joe Spraggins directs with able assistance from Rupert Lacy, a veteran law enforcement officer whose history, knowledge, and respect for the power of the storm enabled him to oversee operations for all emergency support functions and, later, succeed his boss as emergency management director. Gary Hargrove, a trained paramedic who was elected to multiple terms as coroner of Harrison County, set aside his own family’s predicament to lead search and rescue, then recovery, and, finally, identification of each person Katrina killed in his county. And Steve Delahousey, veteran EMS leader on local and national levels, made sure people with special needs were moved from harm’s way before the storm and that adequate medical care was available after.

This book documents the players’ personal and professional views as they reveal their alliances and actions, their concerns and issues, their truths and consequences. Theirs are stories about human suffering and survival—often not because of but in spite of assistance from the government. The book does not distinguish right from wrong or comment on whether individuals or organizations succeeded or failed. Readers must draw their own conclusions.

These stories—the characters’ perspective on the problems they encountered and what they themselves revealed to be their values through the storm of the centuries—can bridge to whatever becomes the United States’ and the Gulf Coast’s next Katrina.

As a journalist and public health communicator, I remain grateful to those who shared their “voices from Ground Zero.” Special gratitude to my book’s hero, Dr. Bob Travnicek, who moved to the Gulf Coast in 1990, bringing passion for public health, an outsider’s perception of how to get things done differently, and twenty-two years’ solid experience as a private family practice physician in Nebraska.

Travnicek became the first face of public health, the doc-in-charge for routine population-based health matters and the leading expert for all-hazards preparedness and response. And in that place, he learned from Wade Guice, director of Civil Defense in Harrison County for thirty-five years from 1961-1996, who spent most of his life preaching hurricane preparedness around the world. In that place in 2005, Travnicek firmly faced Mississippi’s greatest threat, Hurricane Katrina.

From 2008 through and after publication, Travnicek persuaded, encouraged, and contributed to my authoring Katrina, Mississippi: Voices from Ground Zero. He and other first responders remain “Champions of the Storm,” immortal—as Faulkner proclaimed—because they have “a soul, a spirit capable of compassion and sacrifice and endurance.”