Image from Emmett Till and Mamie Till-Mobley: Let The World See

A mother’s decision to invite the public into the horrors her son experienced caused a “ripple for justice” that is still felt today.

A mother’s mission to show the world what happened to her son – in hopes it would create change.

That is what the Emmett Till and Mamie Till-Mobley: Let The World See exhibit puts on display for children. The interactive display provides a look into the story of what happened to Emmett in a way young minds can absorb.

Emmett Till was a 14-year-old African American boy, born and raised in Chicago, Illinois. During the summer of 1955, Emmett went on holiday, visiting family in Money, Mississippi. Just days after his arrival in the South he was abducted, beaten, tortured, and killed after being accused of whistling at a white woman.

The exhibit displayed within the walls of the Two Mississippi Museums, paints a picture of a typical young boy ready to embark on a summer adventure. His mother, Mamie, tried to prepare her young son for the culture he would encounter in the deep south at that time.

“How do you give a crash course in hatred to a boy who has only known love?” Mamie is quoted as saying on one of the first panels when you arrive in the exhibit.

The exhibit catalogues an event that took place over the course of his first few days in the state. An event that would ultimately lead to his death.

While at a country store, Emmett encountered 21-year-old Carolyn Bryant. She was a White woman married to the owner of a grocery store in town. Upon this encounter, it was said that Emmett whistled at Bryant, which was a behavior many in the Jim Crow-era South did not take kindly to.

“It scared us half to death. A Black boy whistling at a White woman? In Mississippi? No,” Simeon Wright, Emmett’s cousin and an eyewitness to the event said. “I think Emmett wanted to get a laugh out of us. He was always joking around.”

What happened next is the stuff of any mother’s nightmare.

Emmett was kidnapped out of his great-uncle’s house in the middle of the night. He was tortured. He was beaten beyond recognition. He was then shot and mutilated before his body was discarded in the Tallahatchie River, only to be found three days later.

The men responsible for leading the group were Carolyn Bryant’s husband, Roy Bryant and his half-brother J.W. Milam.

Because the exhibit is geared toward children, it does not go into the graphic details of Emmett’s death, but it does explain what happened to him and what transpired after he was found.

“They don’t show the horrific side of [Emmett’s death]. I think that is bad for children to see,” said Pamela D.C. Junior, Director of the Two Mississippi Museums. “It really gives you mom’s [perspective] and allows people to see what happened to her baby.”

The exhibit displays the proceedings within the courtroom, a scene one can only describe as a shocking injustice to Emmett and his family.

Both Bryant and Milam openly confessed to killing Emmett, yet the jury did not convict them.

The jury, made up of only White men, deliberated for 67 minutes before finding the two, “Not Guilty.”

But Emmett’s mother, Mamie, would not allow that to be the end of her son’s story.

She fought to have Emmett’s body taken back to Chicago and buried. And while many discouraged her, she chose an open casket funeral, where over 100,000 visitors witnessed up close the horror inflicted on her child.

Photographs of the massive crowds gathering to attend his funeral are on display within the exhibit.

“Let the world see what they did to my boy,” Mamie was quoted as saying.

A piece of art by Lisa Whittington hangs just a few feet from the opening of the exhibit. It shows what Emmett looked like when he left his mother and then what he looked like when his body was recovered. When he was returned to Mamie, Emmett’s face was bloated, disfigured and nearly unrecognizable. This scene, Junior said, often resonates with mothers and fathers, depicting the cruelty this kind of hatred creates.

Junior said people of that time were transfixed on Emmett’s story. It catapulted many young people within the civil rights movement into action, people like, Dorie Ladner, a civil rights activist from Hattiesburg who said many were filled with a desire to avenge Emmett’s death.

“Through this happening, his mom started a movement. The Emmett Till generation,” said Junior. “All of these people, these young folks, they said ‘no more.’”

And the movement did not stop.

The exhibit has on site the original sign that was erected to honor Emmett’s memory at the place where his body was recovered from the river. The sign was placed nearly 50 years after Emmett’s murder when Tallahatchie County citizens came together to tell the story about his death. A public apology was also made to Emmett’s family.

The sign, however, is riddled with bullet holes, a reminder that not everyone wanted that story told.

The exhibit ends with a challenge for young viewers: “What are you going to do?”

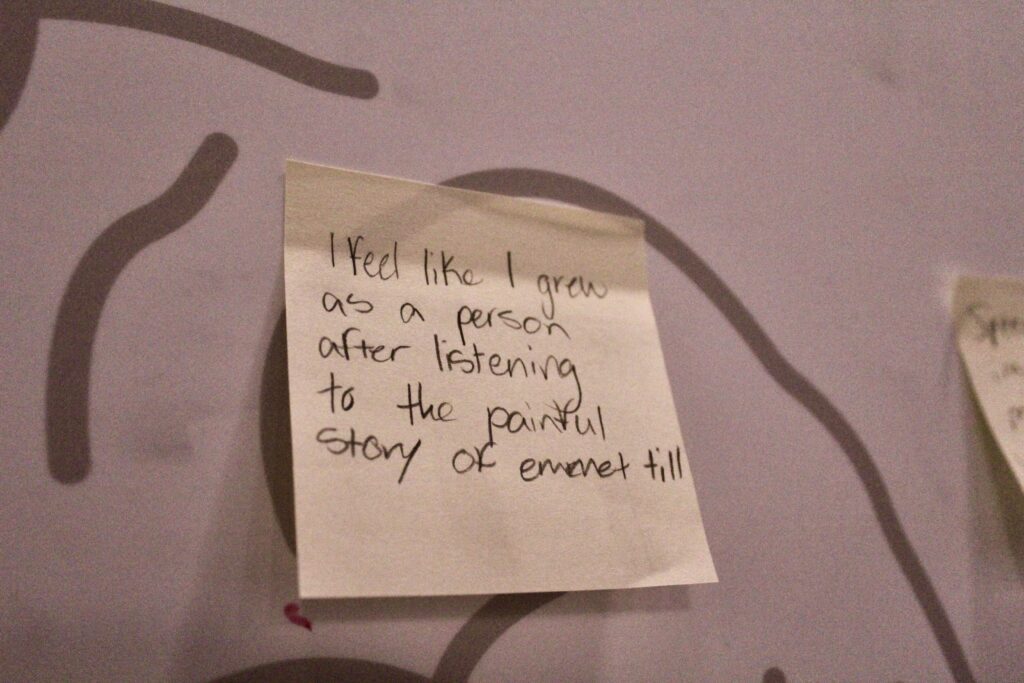

Students left sticky notes about what they had learned in the exhibit and how the story of Emmett Till impacted them as a person.

“Emmett’s mom asked us to bear witness to the tragic murder of her only child. Her brave actions began a powerful ‘ripple of justice,’” reads a final panel in the exhibit.

Mamie’s decision to invite the public into the horrors her son experienced caused a “ripple for justice” that is still felt today as many go on to fight racism and injustice in the United States.

The exhibit was developed by the Till family, Emmett Till & Mamie Till-Mobley Institute, Emmett Till Interpretive Center and The Children’s Museum of Indianapolis. It will remain in Jackson until May 14