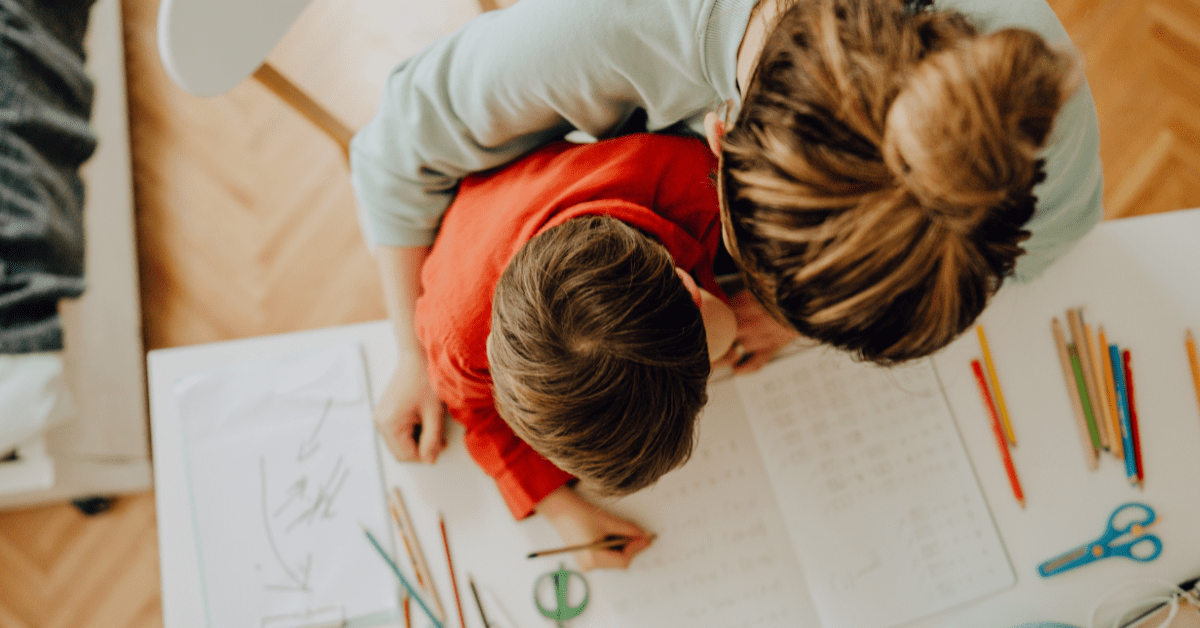

There are misconceptions that homeschooled children are not held to any standards as well as stereotypes that portray homeschooled learners, by and large, to be maladaptive, socially inept, and academically lacking. Statistics show this to be untrue.

Mississippi families who homeschool have a lot of freedom when it comes to their children’s education. Since the only Mississippi Department of Education mandated requirement is that parents notify their local school district that they will be homeschooling each school year, the options available are limitless.

According to Mississippi law, a child must start an education path, whether at home or in a school, by the age of six. Many families homeschooling choose to wait until their children reach this age to start what would be considered their kindergarten year.

Others start sooner.

That’s the case for Sarah Pradillo and her daughter. Pradillo has always been intentional with how she structured her day with her children. Intentional play and exploring interests from a young age fostered a constant learning environment in the Pradillo household.

“Homeschooling has always been our plan,” said Pradillo. “I read that if you homeschool until they grow up and leave, you have 18,720 more hours with your kids than if they went to school.”

Pradillo said that maximizing time with her kids, along with being able to personalize their education, based on each individual child’s needs and interests, has been a driver for homeschooling.

“My daughter, the other day, was doing her reading in her chapter book aloud, which is part of what we had to do that day,” said Pradillo. “But she was able to do that while riding her tricycle in circles in the den. She doesn’t have to sit still. We can do this however we want to do it.”

Pradillo said she is motivated by the progress she sees in her children.

“I get to see that moment when it clicks, and they can read,” said Pradillo. “And I get to see how they light up when addition starts to make sense. I don’t miss those moments. I get to see them play together, grow together, and learn together.”

Flexibility and freedom, Pradillo said, are some of the great perks of homeschooling.

“They will get an individual education, based on their needs, how fast they learn something, and it won’t take as long,” said Pradillo. She added that since a typical day of learning in homeschool doesn’t take as long, they have more ability to explore other things.

“We get a lot of time for enrichment, extracurricular activities, and exploring other interests,” said Pradillo.

Teacher decides to leave classroom to homeschool own children

Beth Thrasher is a mom of two. She’s also a teacher. She says she knew from her own teaching experiences that she would be homeschooling her children.

“I taught in South Jackson for twelve years,” said Thrasher. “And I’ve just come to realize that I don’t know if there’s any amount of money or legislation that could fix what we’ve created in the public school system.”

Thrasher claimed that her training as a teacher encouraged her to make data-based decisions for her students, but added that the whole education system flew in the face of data-driven decisions.

“The whole system ignored that philosophy,” said Thrasher. “Research shows homework is useless. ‘Well, no, we have to have homework.’ But why?”

The former teacher said when she entered her first child into the public school system, she encountered even more inconsistencies with evidence-based education practices.

“Studies show that elementary students should spend half their time playing,” Thrasher said.

“But then we have threats that students lose recess if they don’t perform well on such and such test or behavior. These were kindergarteners. It was crazy.”

This disconnect that Thrasher noted is not new. As early as 2006, The American Academy of Pediatrics observed that with each school year, children’s abilities to store new information have shifted as outlets for play and physical expression were being reduced at school. According to that AAP study:

“Currently, many schoolchildren are given less free time and fewer physical outlets at school; many school districts responded to the No Child Left Behind Act of 2001 by reducing time committed to recess, the creative arts, and even physical education in an effort to focus on reading and mathematics.”

Fast-forward over a decade, and the AAP is noting even more detrimental impacts of the loss of playtime:

“The benefits of play are extensive and well documented and include improvements in executive functioning, language, early math skills (numerosity and spatial concepts), social development, peer relations, physical development, and health, and enhanced sense of agency. The opposite is also likely true; Panksepp suggested that play deprivation is associated with the increasing prevalence of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.”

These disconnects drove Thrasher not only to homeschool her children, but also to find the best format that served them.

“I really tried to model learning for them,” said Thrasher. “If I was learning something new, I tried to show them ‘Mommy’s writing this down; Mommy’s going to watch a video or read a book about this later.’”

Thrasher sparked interest-based learning in her children and varied the curriculum to meet them where they were.

“You’re always looking for learning,” said Thrasher. “Are they engaging with their environment? Are they expanding their vocabulary? Are they asking questions?”

For example, when Thrasher’s daughter wanted her to buy something, it was the perfect time to teach her about math and personal finance.

“She knew I was teaching (online) classes at the time,” said Thrasher. “So I asked her things like ‘how many classes would I need to teach to buy you that?’ and she would come up with the answer and get back to me.”

Thrasher said the same applied to teaching other subjects. If they were traveling, they’d hone in on what they saw around them and have conversations about the geography they were seeing or the history of the area.

“Whatever they show interest in, you just lean into it,” said Thrasher.

Thrasher said this constant learning mindset, along with a routine and supplementing with co-ops and extracurriculars, has provided her children with a well-rounded, well-adjusted education.

Despite narratives, homeschooled children perform well

There are misconceptions that homeschooled children are not held to any standards at all. There are stereotypes that portray homeschooled learners, by and large, to be maladaptive, socially inept, and academically lacking.

Statistics show this to be untrue.

When it comes to academic performance, homeschooled students often outperform their public school cohorts.

The National Home Education Research Institute (NHERI) study showed that “homeschoolers typically score 15-30% higher than public school students on standardized tests. The average score for a homeschooler ranges between 85% to 87% while public schoolers score around 50%.”

In terms of socialization, co-ops, microschool programs, city recreation leagues, and other social outlets provide entertainment and enrichment in social settings for homeschoolers.

Many homeschoolers still have a prom, field trips, etc., outside of the traditional schooling setting. How students perform socially outside of their own circles, though, is admittedly split in the bodies of research because the definition of social skills can vary from study to study, and often, the results of those studies vary widely.

Part of the reason for the variance, according to Education and Behavior, is that the questionnaires involved in these studies are often subjective, with much room left for interpretation. One study may show that homeschooled students and traditionally schooled students score nearly the same when it comes to social skills, while another may have one student population outpacing the other.

Homeschooling parents in Mississippi may not be held to specific state standards, but they do their own homework to prepare their learners for college.

Ashley Sigrest, a homeschooling mother of four, has taken the lead in the education of each of her children during their entire lives. Her oldest, Brady, has started at Mississippi College this fall.

“The moment he started high school, we planned classes based on working toward college & his interests,” said Sigrest. “I asked other homeschool moms (about curricula) who had graduated kids who went to college and researched those before I chose (the best path).”

Sigrest said her job as a homeschooling parent to Brady shifted as he approached high school; she was more of a guide, urging him to become more of an independent learner– a skill needed for college.

“…By the teens, your child should be an independent learner able to read and follow directions for themselves. I became more of a facilitator, helping him as needed & discussing various things with him to ensure his understanding. We also utilized some local, in-person classes,” said Sigrest.

Brady received the Speed Scholarship at Mississippi College, which covers his full tuition.

“Having been an independent learner for most of high school education, he’s used to studying independently and preparing,” said Sigrest. “He’s joined a club and is involved in many student activities.”

The Coalition for Responsible Home Education outlined studies on how homeschool students fare once they become adults; in college, they fared on par or ahead academically among their peers, with math being the one subject that seemed the largest struggle. One of the very first studies of its kind, “Homeschooling Grows Up,” showed that homeschooled students become well-engaged civilians and continue to value their learning into their adult years.

Parents of homeschooled students research college entrance requirements and get transcripts, diplomas, and any other necessities together when helping their child apply for college. Third-party organizations, such as co-ops, can help with this process as well.