Dr. Bob Graboyes

Columnist Robert Graboyes says Mississippi could set itself up as a magnet for healthcare professionals by lowering barriers to the supply of caregivers.

For decades, our national healthcare debate has focused on, “How many people have an insurance card in their wallet?” For a decade, I’ve argued that we should focus instead on: “How do we provide better care for more people at lower cost, year after year?” Many policy actions could contribute to that goal; over the years, one of the recurring answers has been, “Make better use of advanced practice registered nurses (APRNs).”

Health insurance is important. But the American political system has allowed its concern with coverage numbers to drown out conversations over who provides our care—and when, where, and how they provide it. If the supply, quality, and timeliness of care aren’t adequate, then insurance coverage can be a hollow promise. Health insurance is to healthcare what a check is to cash. A check is a promise of cash, but it’s only valuable if the signer has adequate funds in the bank. Similarly, a health insurance card in your wallet is a promise of care—only useful if there are providers standing ready to offer you the high-quality services you need.

This was illustrated bluntly in a 2005 case before Canada’s Supreme Court. Canada has “universal” coverage—every single Canadian has insurance. But medical authorities in Quebec told one Canadian that he would have to live in pain for a year before they could fit him into their schedule for a hip replacement. He and his doctor filed a lawsuit, and in a 2005 ruling, Chief Justice Beverley McLachlin slammed Quebec’s insurance and care, writing: “Access to a waiting list is not access to health care.” In many parts of America, insurance cards offer access to a waiting list or to care somewhere far from home. With its vast rural landscape, Mississippians are all too aware of this problem.

The Affordable Care Act (ACA, or “Obamacare”) helped reduce the percentage of uninsured people in America from around 16 percent in 2010 to just under 8 percent today. (In Mississippi, the equivalent figures were around 21 percent in 2010 and 10 percent today.) Mississippi is pondering a Medicaid expansion under the ACA to boost those numbers. Governor Tate Reeves has floated the idea of increasing Medicaid reimbursement rates. Again, not to denigrate the importance of coverage, but all of these policies involve adjustments to the DEMAND for healthcare, not to the SUPPLY of healthcare. None of these policies directly adds extra doctors, nurses, hospitals, clinics, etc. As for costs, by increasing demand without increasing supply, these policies most likely drive costs up, not down.

Supply-side reforms are different. In 30 or so years as a health economist, the single most important quote I ever ran across came from John Cochrane, a scholar at Stanford University’s Hoover Institution. In a 2012 piece called, “After the ACA,” Cochrane wrote: “What’s the biggest thing we could do to ‘bend the cost curve,’ as well as finally tackle the ridiculous inefficiency and consequent low quality of health-care delivery? Look for every limit on supply of health care services, especially entry by new companies, and get rid of it.”

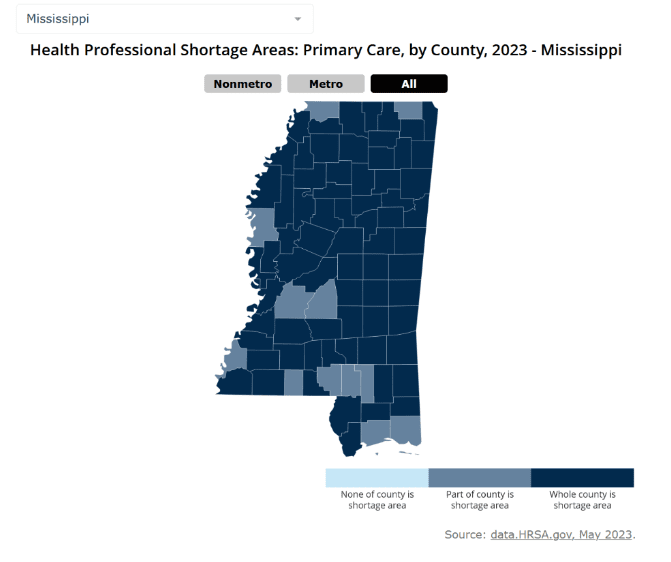

America has a particular problem with the supply of health care services—limited availability of healthcare providers, and especially of doctors. The problem is especially acute in Mississippi. Being in limited supply, healthcare professionals are in limited supply, giving them wide berth in where to practice. Compensation is considerably higher in cities, so it’s particularly tough to recruit an adequate number of doctors to rural areas anywhere in America. Mississippi’s per capita income is the lowest of any state, so doctors know they can earn more money elsewhere. This shows in the following map, from the Rural Health Information Hub, based on U.S. Department of Health and Human Services data. As troubling as this map is, things are likely to worsen over the next few decades as population growth, and especially population growth among the elderly, strain the healthcare system’s capacity even further.

That’s where APRNs come in. These are nurses with intensive specialized training and post-graduate educations. Examples include nurse practitioners, nurse midwives, nurse anesthetists, and clinical nurse specialists. They often hold doctorates, such as a doctor of philosophy (PhD), doctor of education (EdD), doctorate of nursing practice (DNP), or doctor of nurse anesthesia practice (DNAP). APRNs aren’t medical doctors, so there are many medical services that neither their training nor their licenses will allow them to perform. However, they are highly skilled at what they do, and they know what they cannot do. APRNs provide high-quality service in the areas in which they are trained. There are lots of them. And, typically, they are less expensive than physicians. This is where it’s prudent to follow Cochrane’s advice: “Look for every limit on supply of health care services, especially entry by new companies, and get rid of it.” In the case of APRNs, there two broad ways to lower barriers to supply:

- Expand licensure. Make it easier for an APRN to obtain a license in Mississippi.

- Expand scope of practice and autonomy. Let APRNs do everything they’re qualified to do, and don’t require APRNs to be “supervised” by doctors.

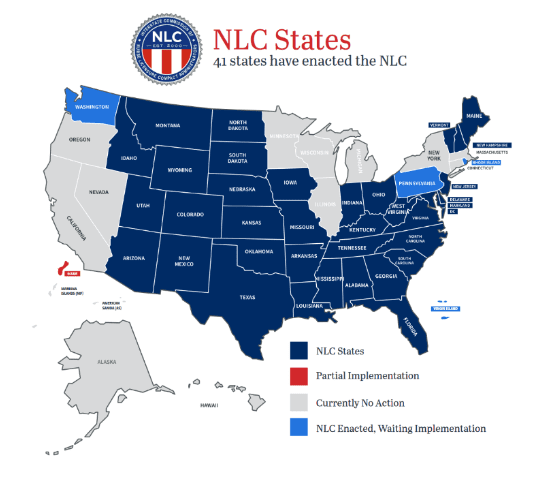

On licensure, Mississippi is in rather good shape, compared with some other states. The state is a member of the Nurse Licensure Compact (NLC). Under this arrangement, “Nurses holding a multistate license can practice in other NLC states/territories, without obtaining additional licenses, while maintaining their primary state of residence (PSOR). The multistate license is issued in a nurse’s PSOR, but is recognized across state lines, like a driver’s license.”

However, Mississippi could go a step farther. Arizona has a unique arrangement that Mississippi could emulate. Most NLC states freely admit nurses from other NLC states. But Arizona admits nurses licensed in ANY other state, NLC or not. (Arizona does the same for doctors and for most other licensed professions.) A doctor or nurse in any state in the Union can move to Arizona, present his or her credentials in good standing, and begin practicing immediately. (Once that happens, the practitioner begins the process of obtaining an Arizona license, but he or she need not wait for that process to play out.)

Notice that California, Illinois, New York, Massachusetts, Michigan, and Wisconsin (all experiencing large out-migrations of population) are not members of the NLC. Nurses in those states cannot simply move into NLC states and set up practice—with the exception of Arizona, with its unique law. Hence, Arizona has set itself up as a magnet for healthcare professionals looking to leave those out-migration states. Mississippi could do the same, if it wished.

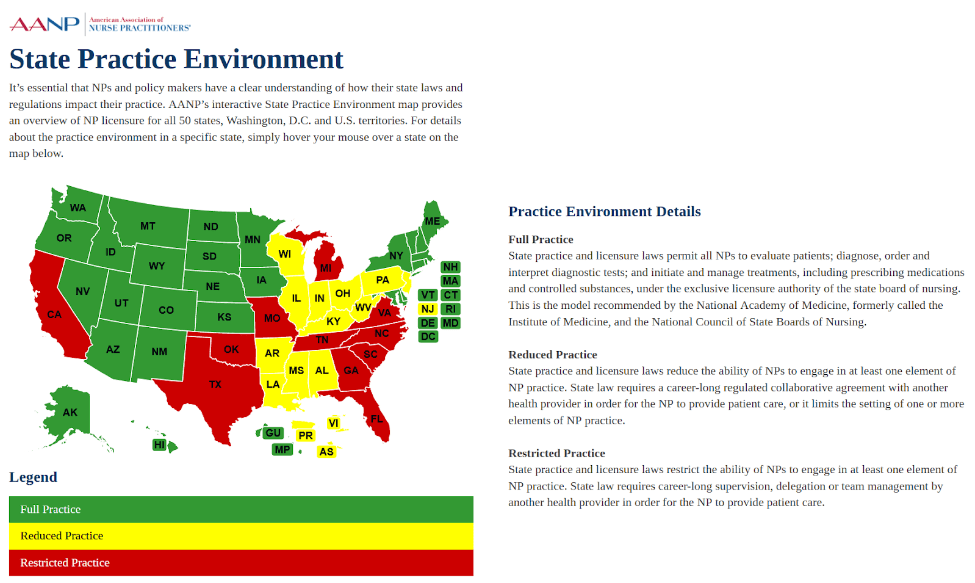

Then there are two interrelated limitations on the supplies of APRNs. The following map is from the American Association of Nurse Practitioners. States in green allow NPs to do all the tasks they are trained to do, and they do not require NPs to be supervised by doctors. States in red prohibit NPs from doing many tasks for which they are trained and/or require that NPs be supervised by a physician. States in yellow, including Mississippi, prohibit NPs from performing some tasks for which they are competent and require collaborative practice agreements.

If Mississippi wishes to expand its supplies of caregivers, it can take those actions that will turn the state green on this map.

#####