Dr. Bob Graboyes

Advocates suggest that expansion will be inexpensive, improve poor people’s health, and save rural hospitals. Unfortunately, these claims crumble under scrutiny.

In 2009, Oregon’s Democratic Senator Ron Wyden told the Wall Street Journal, “Medicaid is a caste system. It is unfair to poor people and it is unfair to taxpayers.” Paraphrasing Wyden, the article said Medicaid, “makes it hard for physicians to take care of the most vulnerable in society.”

Wyden was correct in 2009. His words remain correct today.

However, nine months after that article was published, Congress passed the Affordable Care Act (ACA), which included a massive Medicaid expansion. Since then, 40 states and D.C. have agreed to the expansion, with heavy pressure for the remaining 10–Mississippi included–to fall in line.

Advocates suggest that expansion will be inexpensive, improve poor people’s health, and save rural hospitals. Unfortunately, these claims crumble under scrutiny.

Even still, legislators will find it difficult to resist Medicaid expansion for the same reason that people watch Facebook videos while driving and argue ferociously with nasty strangers on Twitter (“X”). It’s the same reason a tinkly melody lures me outside to buy ice cream from Mister Softee when my cardiologist has told me to lose weight. (Mississippians can substitute “Blue Bell” for “Mister Softee.”)

Like Facebook, Twitter, and Mister Softee, the ACA’s authors crafted the Medicaid expansion to be irresistible to state legislators—even those who agree that the program is unfair to poor people and taxpayers. To understand how, let’s start with some history.

The ACA became law in 2010, but from 2007 to 2009, much betting in Washington focused on a different proposal, “Wyden-Bennett” (named for Wyden and Utah’s Republican Senator Robert Bennett). Far more radical than the ACA, Wyden-Bennett attracted support from Republicans, including Mississippi’s Trent Lott.

Wyden-Bennett would have shifted people from employer-sponsored policies into an individual market, where people would have shopped for health insurance as they do car and homeowner’s insurance. Wyden-Bennett would have eliminated Medicaid altogether, with subsidies enabling lower-income Americans to purchase the same health insurance policies as their wealthier neighbors. Then, patients of modest means wouldn’t face doctors saying, “Sorry. We don’t take Medicaid patients.”

I didn’t support Wyden-Bennett, but was impressed by its ambition and intellectual coherence. Despite bipartisan support, it didn’t happen. Instead, Washington lobbyists conducted a months-long quilting bee to stitch together the ACA—a messy patchwork comforter to keep interest groups snug and warm while crowding more Americans under the thin blanket of Medicaid.

Medicaid spends piles of money to obtain modest improvements in health. In 2008, Oregon offered researchers a rare opportunity to measure Medicaid’s actual impact on enrollees’ health. Oregon wanted to expand its Medicaid rolls but didn’t have money to cover all potential enrollees. The state held a lottery, with around 40% getting coverage and 60% not. Over several years, a research team observed both groups and found that those who received Medicaid exhibited only a few small and ambiguous health improvements versus those who didn’t.

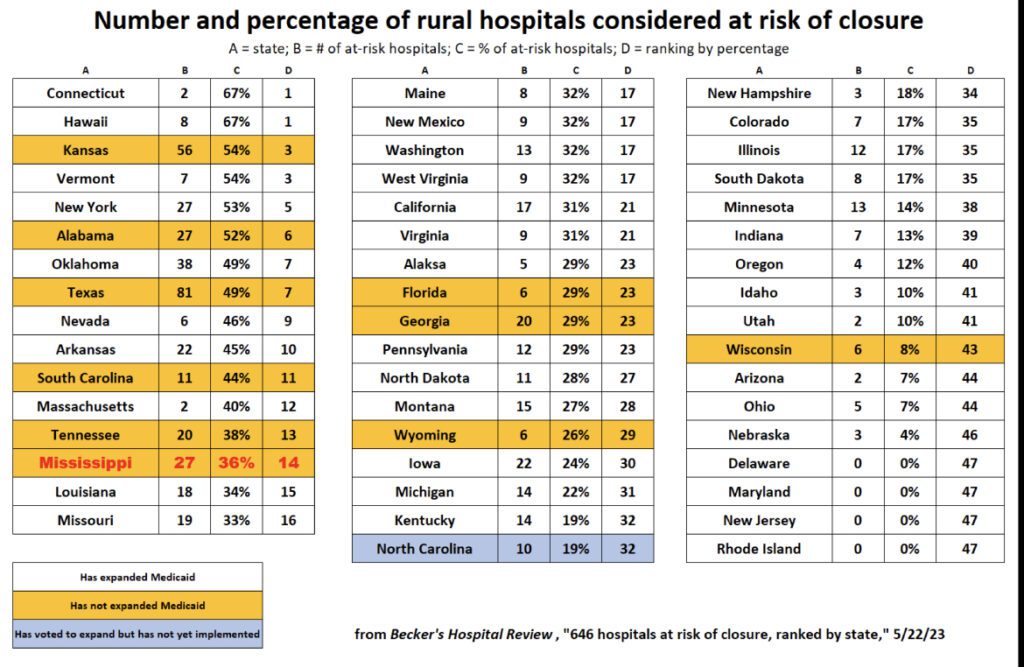

It also isn’t clear that rural hospitals fare better in expansion states than in non-expansion states. In the adjacent table, 6 non-expansion states rank fairly high in terms of closure risks but the other five (including North Carolina, which has not yet implemented its expansion) do not. Eight expansion states have a higher percentage of at-risk hospitals than Mississippi, and numerous expansion states have only marginally better percentages than Mississippi. And this table doesn’t provide evidence that Medicaid expansion has much impact on these rankings.

Why, then, have 40 states and D.C. followed Oregon’s lead in expanding Medicaid? That’s where Facebook, Twitter, and Mister Softee come in.

Social media employ pleasure and pain to encourage activity. Facebook “likes” give users dopamine highs similar to those experienced by drug-abusers. Twitter’s engineers know exactly how to encourage angry conflict, thereby generating clicks and advertising dollars. Ice cream vendors understand that tinkly music makes you think of frozen confections.

DOPAMINE & DENIAL

The Medicaid expansion was crafted to generate similar effects on politicians, and the strategy was brilliant. A politician who votes “yes” can say, “I gave insurance to thousands of poor people,” or “I brought millions in revenues to rural hospitals.” Voting yes reduces political opponents’ capacity to say, “He wants to deny poor people healthcare,” or “She wants rural hospitals to close.”

But the expansion’s real magic was its financing formula. Legislators enjoy pleasure and avoid pain while foisting most costs onto other states’ taxpayers. If Mississippi expands Medicaid, Mississippians pay only 10% of the cost. Other states’ taxpayers cover most of the other 90%. To understand why, here’s a simple analogy. It’s not precisely how the Medicaid funding works, but it’s close enough to give an idea:

Instead of 50 states plus D.C., substitute 51 people at a restaurant. The chef’s signature dessert costs $100, and not one of the 51 diners would willingly pay that much out of pocket. However, the deal is that each diner who orders a dessert pays only $10 out of his or her own wallet, with the remaining $90 split with the other 50 diners. Suppose 41 diners have already ordered the dessert, and you’re one of the 10 holdouts. If you don’t order the dessert, you’ll pay $72.35 for those who did (=$90×41÷51). If, instead, you order one, you’ll pay $84.12 (=$10 + $90×42÷51). So, for an extra $11.77 (=84.12−$72.35), you can enjoy a $100 dessert.

Ultimately, everyone ends up spending $100 for a dessert no one thought was worth $100. All 51 diners could have said “no thanks,” left the restaurant, and bought a $6 cone from Mister Softee. Of course, we’re not talking about a $100 dessert, but hundreds of billions of dollars spread out across taxpayers, including taxpayers in Mississippi.

TEN THOUGHTS FOR FUTURE DISCUSSION:

- Medicaid expansion financially favors childless adults with incomes just above the poverty line over traditional Medicaid recipients (e.g., low-income children, pregnant women, senior citizens, and disabled).

- Expansion may reduce care for traditional recipients, as the two groups will compete for scarce resources. As of late 2022, per capita Medicaid spending on children in expansion states had grown less than one-third as fast as in non-expansion states.

- Expansion enrollees will also compete with non-Medicaid patients for scarce resources.

- Rural hospitals face many threats, including declining populations and a shift from inpatient to outpatient care; there’s no guarantee that expanding Medicaid can overcome these factors.

- In other states, the enrollment and costs of expansion have often been far higher than initially forecast.

- With federal budget deficits out of control, reducing Medicaid reimbursements will certainly come under consideration.

- Medicaid often pays providers less than the cost of the care provided. One might ask whether “higher revenues” is a winning strategy when accompanied by “even higher costs.”

- For those worried about the financial viability of rural hospitals, perhaps rural areas would be better served by more clinics, urgent-care facilities, and ambulatory care facilities.

- The field of medicine has become highly politicized, and the federal dollars and oversight in Medicaid will give Washington, DC, greater leverage over states in imposing its political agenda.

- Finally, it’s good to recall Blahous’s Ten Laws of Politics—written by my friend and colleague Chuck Blahous, a veteran Congressional and White House advisor. His Law #5 is, “The more sympathetic the constituency, the worse the policy.” “When Americans are asked whether we should spend more or less on a sympathetic cause or group, they will generally respond with ‘more’ before even knowing how much is currently being spent.”