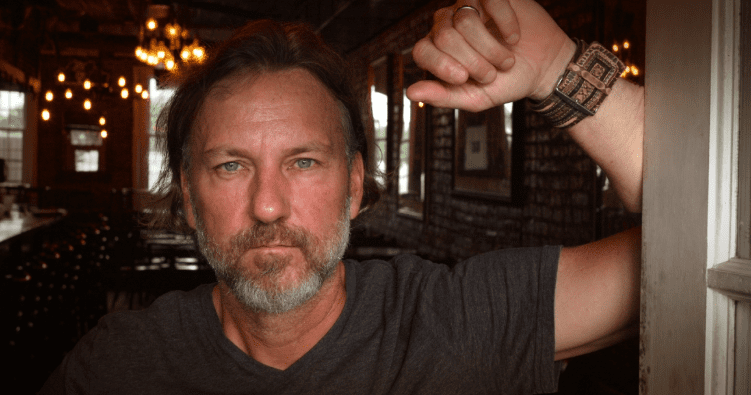

Photo credit: Karen Kuehn

- When impresario Sam Phillips wouldn’t distribute her music, Jackson founded Moon Records and produced her own recordings.

Despite being one of the originators of rock ‘n’ roll — coming up alongside megastars Elvis Presley, Jerry Lee Lewis, and Chet Atkins in the 1950s — the closest Cordell Jackson ever got to mainstream success came in a beer commercial made when she was 68 years old.

Seated in a rocking chair wearing a ball gown and winged eyeglasses, hair fixed into her signature bouffant, Jackson perfectly played the rockin’ granny role. Only it wasn’t an act. The attitude and style, and the way she vigorously strummed her red Hagstrom guitar, were 100 percent real.

“Nowadays it’s no big deal for somebody to be 70 years old and out there doing gigs and stuff, but back then it was a big deal,” says Nancy Apple, a longtime friend of Jackson. The novelty may have helped sell more Budweiser, but to Jackson’s benefit, it also introduced America to a largely unknown music pioneer.

Born in 1923 in Pontotoc, Mississippi, Jackson showed an interest in music early, and by age 12 she would sit in with her father’s string band, the Pontotoc Ridge Runners. As a teen, she developed a whip-fast strumming wrist and began to speed up her proto-rock songs. After marrying William Jackson in 1943, the pair moved to Memphis where she tried to make in-roads to the music scene with movers like Sam Phillips, who founded Sun Records there in 1952. When Phillips wouldn’t put out her music, she took the initiative to forge her own path.

With the 1956 release of the single “Rock And Roll Christmas,” with “Beboppers’ Christmas” as the B-side, she became likely the first woman to produce, engineer, arrange and promote music on her own record label, which she dubbed Moon Records.

“She was one of those people who was like, ‘Girls can do anything boys can do,’ way before there were any kind of movements about stuff like that,” Apple says.

Unlike the more professional studios in town like Sun, Jackson recorded herself and artists like Allen Page and Earl Patterson in her living room. None of the records were hits, though, and for the next couple of decades she focused primarily on making a living, taking jobs as an interior decorator for a real estate company and as a radio DJ on WHER, an all-female station in Memphis, among others.

Musicians like Tav Falco and Alex Chilton gave her stalled music career a boost in the 1980s by inviting her to perform and even covering her song “Dateless Night” in their band, the Panther Burns. Jackson’s music career finally began to reach beyond Memphis, taking her to gritty rock clubs like CBGB’s in New York where she found a new audience for her music.

Jackson began to release music again, including the “Football Widow” single and Knockin’ Sixty EP in 1983, and by the early ‘90s she was making appearances on talk shows like Late Night With David Letterman. That’s also when Budweiser tapped her to appear in a television commercial alongside rockabilly star Brian Setzer of the Stray Cats.

“It was almost as if she had stepped out of a dream,” wrote Howard Fishman in a long-overdue obituary published in The New York Times in January. As Jackson peered “through her old-lady glasses” at Setzer, she displayed her frenetic guitar work while he tried to keep up.

“I always listened to everything she had going on, and she always wrote songs and she would do these kind of cutesy music videos,” Apple says. “She was always very animated and flirty and fun.”

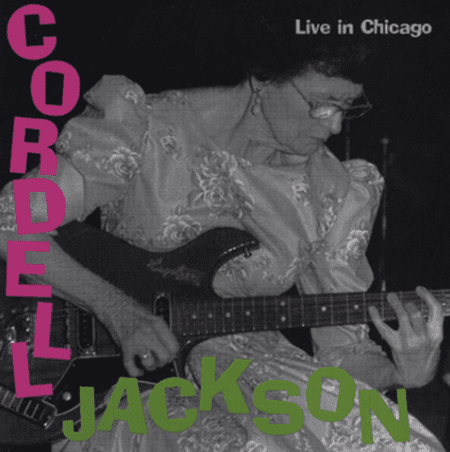

In 1997, Jackson released her only full-length album, Live in Chicago, which includes solo performances of songs from her entire career recorded at a 1995 concert. She continued to perform until her death in 2004 from pancreatic cancer.

Apple, who is currently spearheading a fundraising effort to pay for a Jackson memorial headstone, says she was an icon for women in the music industry.

“She was respected, but she had to work her ass off for it, and it was the younger people that really stood up for her and respected her and saw what it was that she did,” she says. “This whole generation of younger artists, and a lot from the punk rock scene, really adored her.”