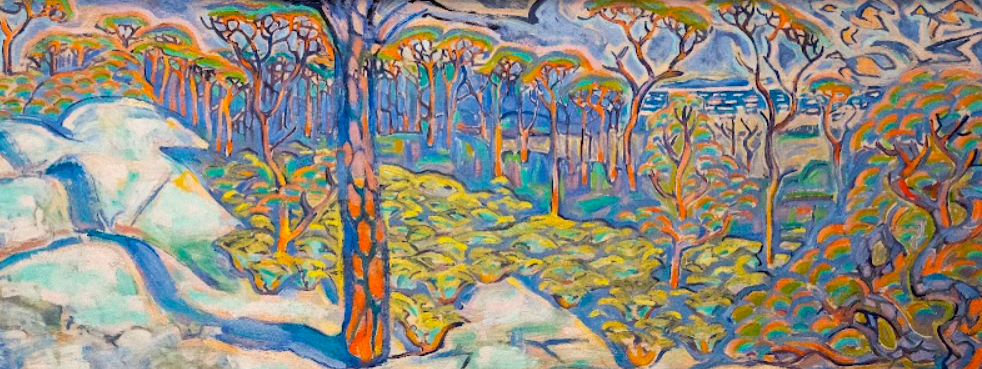

PHOTO CREDIT: Horn Island Oil. c. 1960. Oil on panel, from the collection of the family of Walter Anderson

- Of Walter Anderson’s life, his daughter, Mary, paints a vivid portrait of a father who was not just an acclaimed artist and nature enthusiast but a poetic soul.

Growing up, Walter Anderson’s art was a constant backdrop in my life – from my mother’s baby shower at the iconic Ocean Springs Community Center, adorned with his murals, to a deeper understanding gained through an oral history interview with his daughter Mary Anderson Pickard. His reclusive nature unfolded as layers of mystery, transforming my admiration into a profound connection with the essence of his moral character.

Behind the artist: Walter Anderson and his muse

Walter Inglis Anderson, often called the “most elusive artist,” stands as one of the most unique and captivating American artisans of the 20th century. Born in New Orleans, Louisiana in 1903, to George Walter Anderson, and Annette McConnell, Walter would be the second of the couple’s three sons. In 1922, he enrolled in the New York School of Fine and Applied Art, now Parsons School of Design. A year later he would go on to win a prestigious art scholarship to study at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, it was here he studied under iconic modernists, Henry McCarter and Arthur Carles.

After art school, Walter Anderson moved to Ocean Springs, Mississippi to work as a designer and decorator in the family pottery business. Gaining popularity in the Ocean Springs community, Shearwater Pottery was synonymous with its handmade ceramics and today the business still thrives.

Between the summers of 1927 and 1928, Walter worked at Shearwater. The latter summer Agnes “Sissy” Grinstead visited her parents’ summer estate, “Oldfields” overlooking the Mississippi Sound, in Gautier, Mississippi when she met Walter Anderson on a visit to Ocean Springs. Grinstead, who studied at Sorbonne University in Paris, France, and earned an art history degree from Radcliffe College, shared a passion for artwork and the natural world with Walter Anderson.

In 1933, Walter married Sissy, and the newlyweds moved onto Sissy’s father’s estate Oldfields. This timeframe of bliss seemed to be the catalyst for one of his most productive periods. Their home became a sanctuary of creativity, where Walter transformed the upstairs walls with scenes of land, sea, and air. At Oldfields, Walter found inspiration for his now famed block prints, illustrations of nature, and his favorite fairytales, and fables, a period of translating those pieces of literature into works of art.

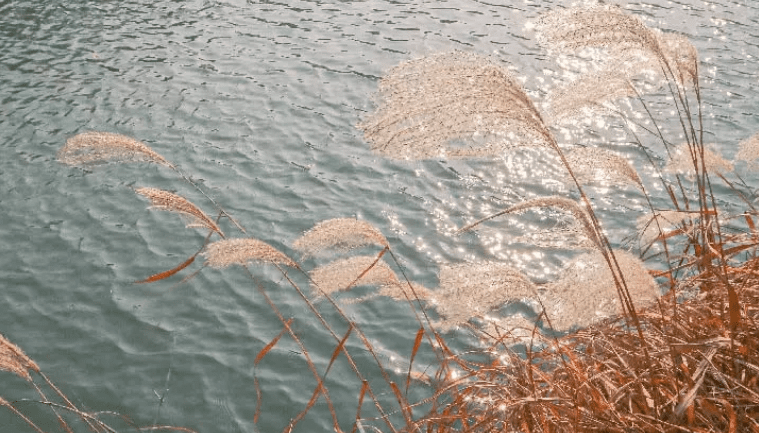

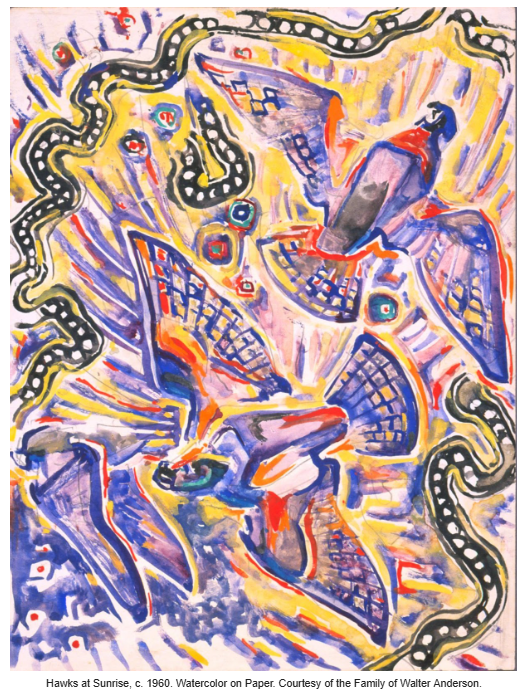

However, his productive period would come to an end in 1946 when he abandoned pregnant Sissy, his three children, Mary (eldest), Billy, Leif, and Oldfields to return to his family’s property at Shearwater in Ocean Springs. Sissy and the children would have very limited contact with Walter, he found solace in being alone in a small cottage on the property to focus on his art, his freedom from the responsibilities of being a husband and father and dreaming of pure solitude was his only demand. He would live out the remainder of his years within the reclusion of the cottage and Horn Island, a barrier island situated twelve miles off the shore of Ocean Springs. Rowing a small skiff to the island, he captured nature’s majesty and power on 8.5 x 11-inch typing paper.

Seeing Anderson Through His Daughter’s Eyes

Of Walter Anderson’s life, his daughter, Mary, paints a vivid portrait of a father who was not just an acclaimed artist and nature enthusiast but a poetic soul. Mary warmly reminisces about her father’s unique ability to turn mere still life into what he beautifully termed “Realizations.”

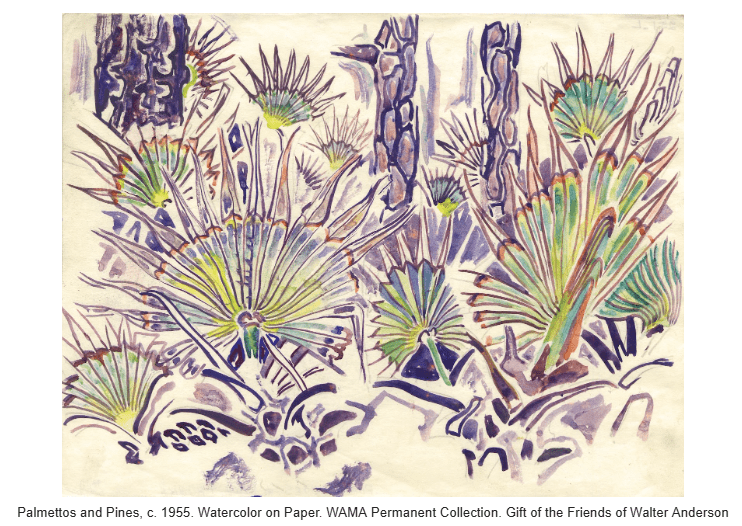

Walter Anderson coined the term “Realizations” to describe his artwork, each piece a flowing canvas—Mary recalls, “he would need to paint it for it to become all the way real to him,” from his block prints of folklore to flights of birds and vibrant depictions of wildflowers in nature. At his cottage at Shearwater, Walter meticulously documented his artistic journey from childhood to his final days, revealing a man who grappled with human frailty and ultimately found transcendence in nature.

Mary fondly recounts how her father’s profound connection with literature, fueled by fables, folklore, and fantasy, ignited his imagination saying, his theory was, “the form is there, the stories are told, realize it like a succession of flowers opening.” Through the prism of his extensive literary pursuits, Walter seamlessly wove tales of creatures, birds, and wildflowers into his drawings, imparting to his children a deep appreciation for the beauty that envelops us. Mary, a devoted guardian of her father’s legacy, cherishes the diverse mediums through which he made his art tangible, from watercolors to commissioned pieces and pottery at Shearwater. Walter’s love affair with nature, particularly flora and fauna, was a source of boundless joy for Him.

For Mary, her father’s world was an enchanting blend of literature and nature. She explored his drawings later in life and discovered poems transcribed on the back of paintings—a glimpse into his reflections or an invitation into a world where words offered solace. Mary, a former educator, thespian, and community arts activist, traces the roots of her passion back to her childhood at the Oldfields property, where her mother taught her to read at the tender age of three.

Mary’s journey involved immersing herself in the family’s library, transforming literary inspirations into fantastical realities along the sandy shores of Oldfields. Her imaginative exploits, from crafting clay bullets to sitting on downed oak tree roots as an imaginative queen, laid the foundation for a life that would intertwine seamlessly with her father’s legacy.

Living with her father until the age of twelve, Mary witnessed his gradual retreat to Horn Island, where solitude became his muse, free from the judgment of opinions, nature’s creatures embraced him throughout his days and weeks on the island. Despite the seclusion, Walter’s love for nature endured. After his passing in 1965, the aptly named “The Little Room”in his cottage at Shearwater, revealed a world of sunrise and sunset depictions—a poignant testament to the cherished island home he immortalized through his visionary eyes.

Walter Anderson inhabited a world so oblivious to his brilliance – he strove for an absolute understanding of nature, and the imperative ability to connect with it through art. In the narrative of Walter’s life, Mary continues to unveil the threads that bind literature, nature, and art into a legacy that transcends mortality, allowing the real-life world of this extraordinary artist to endure, ever vibrant and alive.