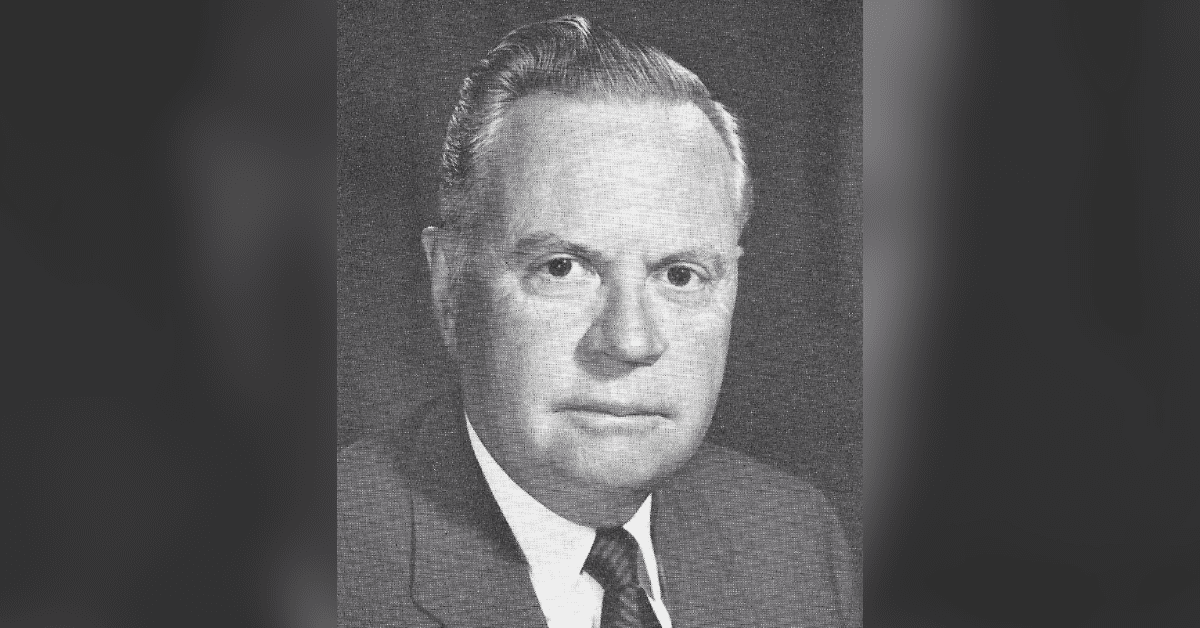

- Turner was born in 1901 on his grandfather’s farm in New Prospect, a backwoods hamlet in Choctaw County.

Longtime executive editor of The New York Times, Turner Catledge, tells the story of his rise from humble and poor beginnings to a position of power and influence as head of a major national newspaper. His 1971 memoir, My Life and The Times, is the stuff of novels and left this reader with great respect for Catledge’s character and integrity. Despite his aggressive ambition and “go-getter” nature, he never lost his Mississippi gentlemanly manners that set him apart in circles where opposing viewpoints are often contentious and even vicious.

Turner was born in 1901 on his grandfather’s farm in New Prospect, a backwoods hamlet in Choctaw County. His father, Lee Johnston Catledge, did not care for coaxing the hard red clay to eke out meager crops of scrawny cotton and lean soybeans. Turner’s mother, Willie Anna Turner, had several successful shopkeeper brothers in Neshoba County. They adored their sister and wanted her close by, so they offered her discontented farmer husband a position in one of their stores.

The Catledges moved to Philadelphia when Turner was three years old. The grand dreams of prosperity never materialized, and the family would navigate poverty during his entire childhood.

Turner learned the value of hard work at an early age. From the tender age of ten, he built an impressive resume of part-time jobs, including delivering groceries, stocking shelves in a hardware store, and keeping the books for his uncles’ various businesses. Although Turner’s dad lacked the business skills of his brothers-in-law, he was passionate about politics and public issues. Philadelphia elected him its mayor, and Turner picked up his father’s interests as he listened to the conversations among the men who congregated around his dad’s office in the county courthouse.

A bonus was peering into the courtroom to take note of local trials filled with fiery rhetoric. The Neshoba district attorney at the time was Woods Eastland, father of longtime U.S. Senator James Eastland, who was Turner’s classmate. He frequently joined Turner, peeking into court proceedings from a hidden vantage point.

When Turner graduated from Philadelphia High School, he enrolled at Mississippi A&M, the school close by that eventually became Mississippi State University. One of his uncles helped pay his tuition, but Turner also worked as a server in the cafeteria to make ends meet. He confides that he was so poor that he borrowed clothes from his friend, John Stennis (who would later become the future Senator John Stennis), whenever he had a date and needed to present himself properly.

When Clayton Rand, publisher of The Neshoba Democrat, hired the industrious young man of fourteen, Turner’s dream of life as a newspaperman took shape. By sheer necessity, Rand, who went on to make a name for himself in journalism, needed extra hands to put out his newspaper on a bare-bones budget. Rand taught Turner to set type, sell advertising, and churn out a story.

Turner was just 21 years old when Rand offered him the opportunity to run his recently purchased Tunica Times, a failing newspaper about 200 miles northwest of Philadelphia. Turner had an innate gift of connecting with people. He immediately immersed himself in his new hometown, becoming a sought-after voice in community matters. The paper flourished at first. The dream fell apart when a conflict arose between the merchants, farmers, and the Ku Klux Klan. The farmers represented the last vestige of Southern aristocracy, and they vigorously opposed the Klan’s intimidating tactics as they watched much of their farm labor migrate north to Chicago or Detroit. The merchants, on the other hand, did not appreciate The Tunica Times’ vociferous criticisms of their friends in the Klan. Ultimately, the lost advertising revenue doomed the once-successful newspaper.

Right away, Turner received a welcome invitation to take over a struggling newspaper in Tupelo, and he was off. With a whopping salary of $22.50 a week, Catledge anticipated a fresh beginning, attempting to turn the newspaper around. However, he was fired after three months for “over diligence.” In an attempt to clean up the financial records of the debt-ridden publication, he offended the editor’s friends and creditors by sending bills to those who were not accustomed to being billed.

Turner’s next stop was Memphis. He arrived in the middle of a blizzard on February 24, 1924, with $2.07 in his pocket. He had planned to apply for a newspaper job with The Commercial Appeal, the paper he respected more than any other on the face of the earth. But as he stood in the snow shivering, he was struck with a severe case of inferiority and walked through the front door of The Commercial Appeal’s second-rate competitor, The Memphis Press, instead.

Several successful stories later, and following a run-in with a hard-driving boss who reneged on his promise of a raise, Turner found the needed courage to march into The Commercial Appeal’s editorial offices and boldly ask to see the publisher, Mr. Charles Patrick Joseph Mooney.

Impressed by Turner’s pluck and audacity, he hired him on the spot. And the rest is history.

hen the mighty Mississippi River wreaked havoc on Arkansas, Mississippi, and Louisiana in 1927, the Mississippi Delta suffered the most significant harm. Twenty-seven thousand miles of flooded land resulted in approximately $14 billion in damage, equivalent to its current dollar value. The catastrophe became the biggest break of Turner Catledge’s life. He spent two exhausting weeks crossing six states, taking photos, phoning in reports to Memphis, and doing newscasts on a local Memphis radio station. His daily stories were far and above any other news outlet’s reporting. When his assignment was almost complete, he returned to his Memphis apartment, which he shared with his widowed mother, and was awakened on a Sunday morning by loud, fist-pounding knocks on the front door.

Two Memphis detectives escorted Turner to a luxury suite in the Peabody Hotel, where Herbert Hoover, then Secretary of Commerce and sent by President Calvin Coolidge, requested a thorough briefing on the flood’s devastation to coordinate relief efforts. Turner’s vast knowledge of the damage and the detailed report of flood victims’ needs so impressed Mr. Hoover that he wrote a letter to Adolph S. Ochs, publisher of The New York Times, telling him he needed to hire this young man.

It would be several years before the Times acted on that recommendation, but they did, and in 1936, Mississippi’s Turner Catledge became deputy chief of The New York Times’ Washington bureau. Years passed as he climbed the corporate ladder, eventually becoming executive editor in 1964.

Turner’s vision and philosophy of a daily newspaper transformed the Times. Perhaps that was just a little related to his roots in Mississippi and his understanding of regular people. Turner never seemed to lose his affection and understanding of his past, even when he confronted the unfolding topic of civil rights. He believed in relating to the average reader by reporting in a way that resonated with them where they lived. Turner encouraged his reporters to write shorter sentences and to always write with the general reader in mind. The purpose of journalism, in his opinion, was to “inform the reader, to bring him each day a letter from home and never to permit the interests of the special interests.”

On the divisive issue of his day — civil rights — his views evolved. He had grown up accepting the oft-repeated “separate, but equal” mantra. Through the Supreme Court decisions of the 1950s, his reporting required that he look at the question with greater scrutiny. He says, “I realized that they [the court and the challenging entities] were right, that segregation in public institutions and facilities cannot be tolerated.”

His political views may have ruffled a few feathers among his Mississippi relatives from time to time. Still, he retained the respect of most Mississippians, at least those who remembered the outgoing, tenacious, and aspiring newspaperman who was committed to the honorable delivery of the facts.

Turner spent his final decade in New Orleans with his wife, Abby, working on his memoir and enjoying the best of life. He died in 1983 after suffering a debilitating stroke.

Turner Catledge embodied the finest among the news shapers during the Golden Age of Newspapers. I love this story. Turner genuinely liked Herbert Hoover, who had helped start his big-time career. Hoover was a Republican. Turner was always a Democrat. Yet, they had a special rapport and respect for each other.

As some questioned Turner in later years about his political loyalty, he answered this way. “I am a Democrat for the same reason the Pope is a Catholic. I was born one, and subsequent developments persuaded me to remain one.”

I probably would disagree with Turner on some things, but I would have loved to have dinner with him. He had tolerance for people with different beliefs. I respect that.