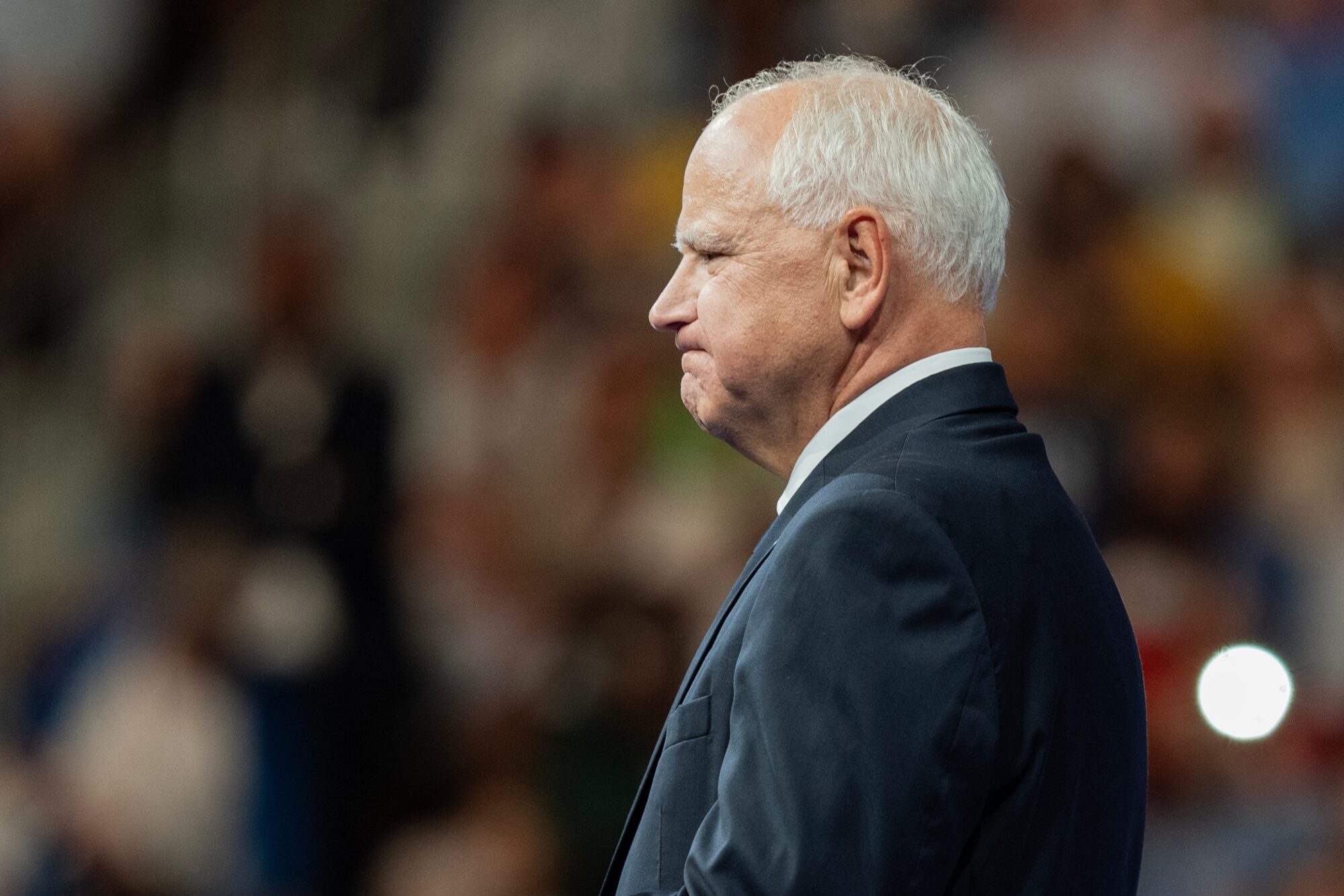

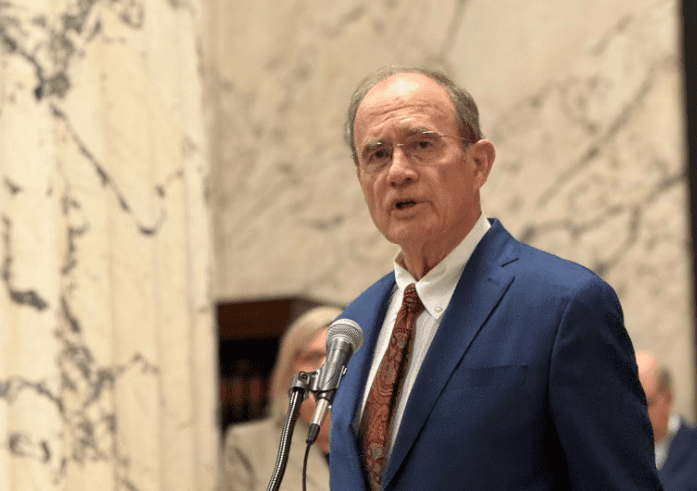

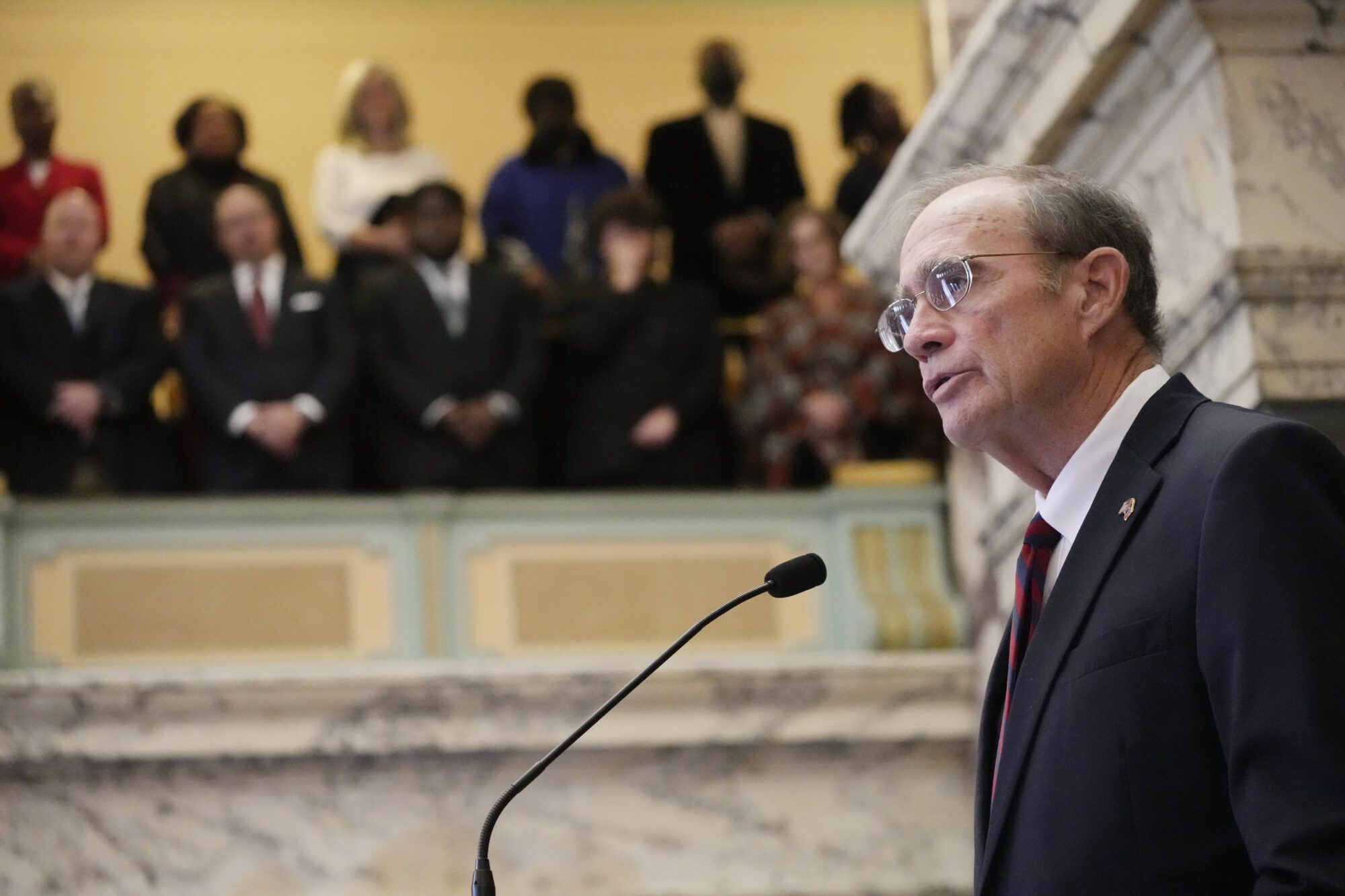

Speaker of the House Jason White addresses the media on Wednesday after Lt. Gov. Delbert Hosemann announced the Senate's new tax plan. He also discussed the expected death of a school choice bill in the House. Photo by Jeremy Pittari | Magnolia Tribune

- Lawmakers should not ignore the concerns of Mississippi’s biggest employers as they wade into a national scrum over PBM reform.

House Speaker Jason White announced Wednesday that a bill to regulate pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) would be sent to conference. Independent pharmacists had aggressively lobbied for the Mississippi House to concur on more stringent regulations inserted into HB 1123 by the Mississippi Senate. But Mississippi’s largest employers warned of potential negative effects on their employees.

White’s move is smart. The issue is complex. Lawmakers weighing regulations should not think myopically, but rather, in terms of what is good for the entire healthcare ecosystem and the broader economy. And first, they should do no harm.

Start by Understanding the Players

Who are the players in the pharmaceutical industry and what role do they play?

- Third-Party Payers: These include private health insurance companies, government payers like Medicare and Medicaid, and private employers who self-fund their own health insurance plans for employees (sometimes called ERISA plans). Third-party payers cover a substantial portion of prescriptions sold in the U.S. in exchange for premiums paid by employers, employees and individuals, or through taxpayer funded programs.

- PBMs: When insurance companies began covering prescription drugs in the 1960s, PBMs were created to negotiate with drug manufacturers and pharmacies on their behalf. PBMs help to decide which drugs Third-Party Payers should cover for certain conditions (known as a formulary list) and how much Third-Party Payers should pay for those drugs. The three biggest PBMs in the country are CVS Caremark (owned by CVS Health), OptumRx (owned by UnitedHealth Group), and Express Scripts (owned by Cigna).

- Wholesale Drug Distributors: For the most part, pharmacies no longer buy drugs directly from manufacturers like Pfizer or Merck. Instead, they buy from Wholesale Drug Distributors who set the prices they charge the pharmacy for the drugs. There are three dominant distributors in the U.S.: AmerisourceBergen, Cardinal Health, and McKesson.

- Pharmacy Services Administrative Organizations (PSAOs): Large pharmaceutical chains negotiate their own contracts for reimbursement with PBMs. Because they buy larger volumes of drugs, they have more negotiating leverage. Independent pharmacies retain PSAOs to negotiate on their behalf and enter into contracts with PBMs. The three biggest PSAOs are owned by the three biggest Wholesale Drug Distributors: Health Mart Atlas (McKesson), LeaderNet (Cardinal) and Good Neighbor (AmerisourceBergen).

Move on to Understanding the Flow of Money

- Purchase of Drugs: Pharmacies buy drugs directly from Wholesale Distributors. The price paid by pharmacies is negotiated based on volume.

- Reimbursement: When a pharmacy fills a prescription it is either paid directly by the consumer or is reimbursed by a Third-Party Payer, often with a consumer “co-pay.” The rate of reimbursement is contingent upon the contract between the Third-Party Payer’s PBM and the pharmacy (or the PSAO that negotiates on behalf of independent pharmacies).

- Rebates: Wholesale Distributors offer rebates to pharmacies, often tied to volume purchases of generic drugs. Drug manufacturers provide rebates to PBMs, who play a substantial role in deciding which drugs Third-Party Payers will cover and the rate at which they will offer reimbursement. 91 percent of these rebates are passed on to Third-Party Payers. This helps to lower the cost of providing health insurance to employees for employers.

- Spread Pricing: This is the difference in the rate a Third-Party Payer agrees to pay for a prescription and the rate negotiated between the PBM and pharmacy or the PBM and PSAO. It’s one of the ways PBMs earn revenue, but has become controversial in the larger national debate over PBMs.

Who’s Making Bank

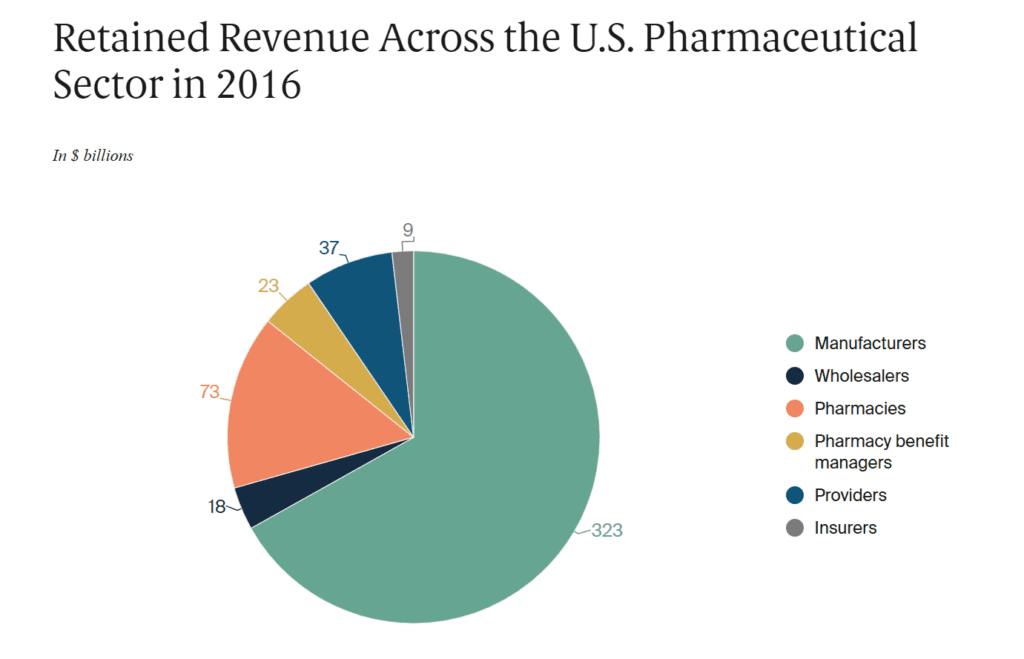

The chart below was prepared by the Commonwealth Foundation using 2016 data. While the amounts and some of the allocation have undoubtedly shifted, it gives good directional insight into how the revenue pie is divided across the pharmaceutical industry.

Revenue by itself does not tell the whole story, though. Amid allegations of “excess,” the better metric would be to look at net profit margin. According to the left-leaning Brookings Institute, the average net profit margin for PBMs is 4 percent. To put that into context, the blended net profit margin of companies in the S&P 500 in the 4th Quarter of 2024 was 12.1 percent.

This is one of the reasons Brookings concluded that even if PBMs were forced to operate without profit it would have a negligible effect on drug prices.

The National Community Pharmacists Association — the trade association representing independent pharmacists — reports the average gross profit margin for independent pharmacists as 21 percent. The NCPA does not report net profit margin, which includes operational expense. This makes a direct comparison of the industries difficult.

Don’t Confuse Anecdote with Reliable Evidence

During the course of this debate, copies of prescriptions with reimbursements below cost have been shared with lawmakers and across social media platforms. It’s important not to confuse anecdote with reliable evidence.

For starters, Mississippi law allows a pharmacist to appeal and be reimbursed in these instances. Secondly, if this happens, it is a result of a contract between the PBM and the pharmacy or the PBM and the PSAO an independent pharmacist retains to negotiate on its behalf. There’s a universe in which independent pharmacists should be questioning their PSAOs (including their “vertical integration” with Wholesale Drug Distributors).

Finally and most importantly, individual examples of below market reimbursements aren’t actually proof of the aggregate impact of PBMs on a pharmacy’s bottom line.

Lawmakers, in my estimation, should not undertake to monitor the profits of private companies, or make efforts to regulate the profits of private companies. In fact, I’d strongly argue against it. Government intervention in markets is a slippery slope. But if you were to undertake such a measure as a prelude to crafting policy, wouldn’t you want to do so for all of the players?

I suspect what you would find is that pharmacy profits are following broader macro trends in healthcare. Pharmacies in rural communities with less economic activity are (on average) doing worse. Pharmacies in suburban community with lots of economic activity are (on average) doing pretty well.

Seeing Forest from Trees

Top-down regulation almost always has winners and losers. Help one industry. Hurt another.

Before the state steps in to monkey with the terms of private contracts, it’s worth considering that Mississippi businesses might actually be telling the truth about the negative impact they would face from the Senate’s proposal.

It’s also worth considering what any proposed PBM reform will do to both consumer and state costs for prescription drugs. After all, what pharmacies are ultimately seeking is higher reimbursements for the prescriptions they sell. It’s pretty naive to assume this will somehow lower the price of drugs.

When Senator Jeremy England asked during floor debate if a fiscal note had been prepared to understand the impact to taxpayers, the answer was “no.”

Finally, it’s worth pondering what the end game is. The head of the Mississippi Independent Pharmacists Association, Robert Dozier, said this bill marks the “start” of reform.

But as long as third-party payers for healthcare — whether the government, health insurers, or private employers — foot the bill for prescriptions, some entity akin to a PBM will exists to negotiate drug prices on their behalf. There’s no way insurers with tremendous purchasing leverage ever just pay whatever pharmacies want (if that’s the utopia people are dreaming of).

I’m sympathetic to the concerns of independent pharmacies. As documented here, the healthcare system is a web of bureaucracy. But caution is the right temperament. Previous national and state attempts to regulate the healthcare marketplace have cumulatively added up to one horribly broken system.