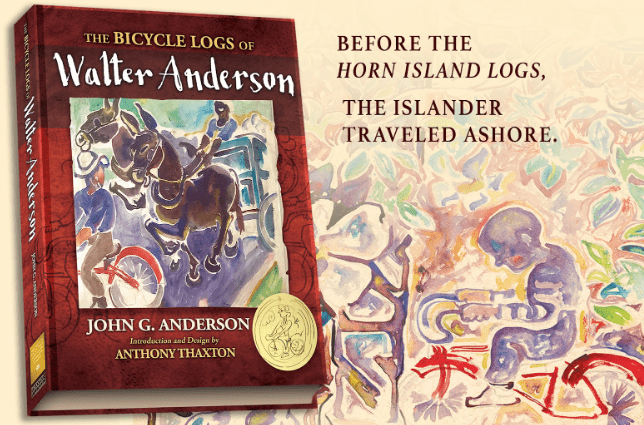

- The artwork and writings collected in ‘The Bicycle Logs of Walter Anderson’ paint a new picture of the acclaimed 20th century artist.

Of all the stories told about the eccentric life of Ocean Springs artist, adventurer and naturalist Walter Inglis Anderson, his frequent sojourns to Horn Island, where he famously slept under his skiff and rode out a hurricane, are perhaps the best known.

Less discussed, however, are his epic wanderings across America and abroad in places like China, where he traveled by bicycle, foot, and even a half-sunken canoe, which he paddled a stretch of the Mississippi River.

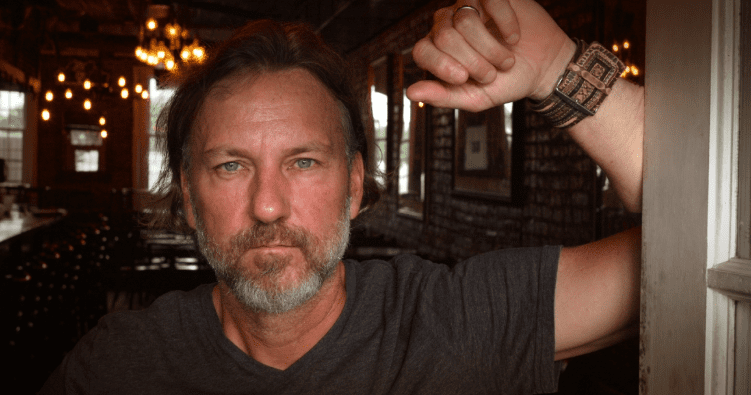

“He was a migratory creature,” says John Anderson, Walter’s youngest son and the author of The Bicycle Logs of Walter Anderson. “He was an explorer.”

The new large-format, hardcover book, designed by Anthony Thaxton and published through the Institute of Southern Storytelling at Mississippi College, collects for the first time the artist’s journals from these journeys, completing a part of his story begun with the 1981 release of The Horn Island Logs of Walter Inglis Anderson.

Intertwined with Walter’s firsthand experiences attempting to walk to Tibet, catching malaria on the Mississippi, and contending with melting bicycle tubes on the hot Texas blacktop, John narrates how his father’s need to explore affected — and influenced — his own life.

“An important part of his story is that we really didn’t know who he was,” John says. “Most of the time when I was growing up, daddy was persona non grata, because he was eccentric, he was referred to as the ‘Horn Island hermit.’ He rode a rusty bicycle around town when everybody else was driving shiny cars. And he lived in an alternative, more natural reality than most people live in.”

John says he spent his youth neither understanding nor appreciating the legacy his father was building by constantly “adding beauty to the world.” He was embarrassed by how his father eschewed modern ways of life, which he called the “dominant mode,” and made the rules of his life according to nature. “Daddy based his reality very objectively on sunrise and sunset, the rising and falling of the tides and the blowing of the wind, the migration of birds and movement of animals.”

After his death in 1965, though, when John was 18, his eyes opened to the acclaim Walter’s artwork earned, and he began to try to learn about him.

“People would show up at Shearwater Pottery, and I remember specifically one lady in front of the showroom — she was all excited and her eyes were sparkling,” he recalls. “She stopped me and said, ‘What was it like to grow up with such an extraordinary artist for a father?’

“Well, I had no idea that daddy was an extraordinary artist. And I didn’t really want to admit that he was an embarrassment to me. I tried to answer her question, but I watched the light get dimmer and dimmer in her as she realized that she knew more about daddy than I did.”

John searched through the physical record of his father’s life — the thousands of drawings and paintings he produced, the pottery he decorated, and the murals he created in Ocean Springs — but didn’t come away with a clear picture until he read his journals. Although he doesn’t believe he has cracked the code and fully comprehends his life, he now sees Walter as a “shaman and mystic,” as his mother Agnes Grinstead Anderson believed, and “a leader, someone who showed us a way out of the trouble that humanity is in right now.”

Through his own travels hitchhiking across the country to Haight-Ashbury in San Francisco and then to New York City, as well as working aboard a ship at sea, John didn’t follow in Walter’s footsteps as much as he staked his own claim in the world. And the person his father revealed in the artwork and writings collected in The Bicycle Logs of Walter Anderson, he says, can point others to an alternate path of life, as well.

“I searched for my father and found myself, so I felt that if other people would search for him, they might find themselves. It meant so much to me to find myself through him and through his art that I wanted to share. It was the most important thing that happened in my life.

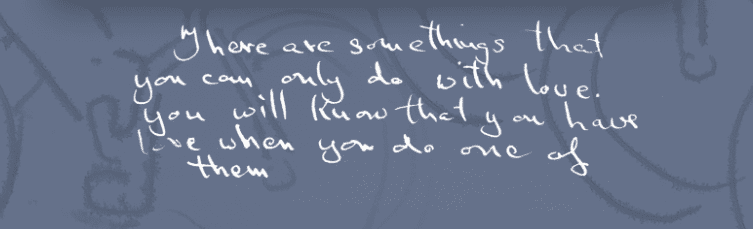

“He changed the world for himself, and that means each of us has the ability to change the world for ourselves.”