FILE - Indiana Fever guard Caitlin Clark signs autographs for fans before the start of WNBA basketball game against the New York Liberty, Saturday, May 18, 2024, in New York. (AP Photo/Noah K. Murray, File)

- The WNBA’s newest sensation has brought in new viewers and new dollars, while performing well on the court early in the season. Unfortunately, her performance has been overshadowed by divisive commentary and rough play.

I find Caitlin Clark to be very interesting.

This makes it quite possible that I’ll watch seconds, minutes perhaps, of a WNBA game this summer, provided certain conditions are met:

- I’m not working in the yard.

- The Braves aren’t on TV at the same time.

- My Kindle lacks adequate battery life.

My interest isn’t in the WNBA. It’s in Caitlin Clark. And I’m not alone. For the first time in history, the NCAA women’s tournament final drew more viewers than the men’s final — 18.9 million to the men’s 14.8 million. The South Carolina Gamecocks defeated Clark’s Iowa Hawkeyes, but viewers came for Clark.

The trend has continued in the WNBA. Clark, drafted No. 1 by the Indiana Fever, draws eyeballs. The Fever’s WNBA games have averaged 1.1 million viewers. Games not featuring Clark have averaged 414,000. However, it’s worth pointing out that’s up from 301,000 last season.

So why the sudden interest? For me, it’s because when she was an All-American at the University of Iowa, she did things on a basketball court that others in the women’s game were not doing.

Logo 3s, they call them. That’s Clark pulling up from just beyond halfcourt and launching shots that would get other players relegated to the end of the bench.

Because other players wouldn’t make them, but Clark did. Every time she’d set one of those shots in motion my internal voice would say, “There’s no way she makes that,” and then she’d knock down another.

But Clark’s success is something more than novelty long-range 3s. Along the way, she set the NCAA all-time record for scoring, surpassing men’s legends ‘Pistol’ Pete Maravich.

One hundred percent of my Caitlin Clark watching came during the NCAA Tournament.

The women’s game was at the forefront of the American sports consciousness.

That’s a good thing.

But that growth was fueled by the success of individuals, like Clark, but also players like Angel Reese at LSU and Paige Bueckers at UConn.

More of the talk around the game centered on these great players than on South Carolina, easily the season’s most dominant team and one that limited Clark’s damage to defeat Iowa for the national championship.

The Reese-Clark rivalry actually captured the nation’s attention a year ago when LSU defeated Iowa for the championship.

The styles couldn’t be more different. The physical, paint-dominating Reese against Clark, the silky smooth guard who not only scores her own points but does a phenomenal job of setting up her teammates with open shots.

Then there’s Reese’s trademark trash talk, a contradiction in style to Clark’s more quiet nature – unless it’s to complain about an official’s failure to call a foul.

Now the rivalry has carried over to the WNBA.

Clark is again dominating the news cycle. She’s the fastest WNBA player to ever accumulate 150 points, 50 rebounds and 50 assists and the WNBA’s “Rookie of the Month” in May.

But the talk these days is less about her play and more about the physical beating she’s taking.

Last Saturday’s Chennedy Carter foul — hammering Clark to the floor while the clock was stopped and away from the ball – was over the top. Carter could be seen yelling what appeared to be an expletive at Clark as she approached for the body check.

It could be considered assault if Clark wanted to pursue it outside WNBA channels. It’s also not the first time on the season Clark has been roughed up. In fact, it’s a regular occurrence. Clearly the league isn’t doing much to protect its golden goose.

The WNBA doesn’t turn a profit and averages a net loss of $10 million a year. It draws having financial support from the NBA to stay afloat.

Now Clark comes in and viewership is up 226% compared to last year while game attendance is up 14%.

The Clark-Reese rivalry is part of the renewed interest, but most of it’s Clark. The end result, though, is more viewers, more money, and more opportunity to showcase talent for all WNBA players.

So why the Clark hate?

Provocateurs like former ESPN host Jemele Hill have suggested that Caitlin Clark’s stardom is a byproduct of her race and sexuality. The View’s Sunny Hostin made similar claims. After Chennedy Carter committed violence against Clark on the court, Hill said Carter, not Clark, was the real victim of the exchange.

Clark is white in a majority black league. Clark has a boyfriend – his name is Connor McCaffery – in a league where almost 30% of players in 2022 identified as something other than heterosexual, according to media reports.

If this somehow boosts Clark’s image with the public, or if other players believe it does, it’s possible that it feeds resentment across the league, playing into what has so far been her rough welcome to the WNBA.

Personally, I think the pounding Clark is receiving is not about race or her sexuality, but comes down to jealousy. There have been great white and straight WNBA players in the past that have drawn neither the attention nor heat Clark is receiving.

It’s very likely now that there are veterans of the game who see Clark’s ascendency as unearned, or as a glaring contrast to the attention they’ve been denied.

Clark’s endorsement deals probably haven’t helped this sentiment. Her $28 million NIKE contract is the signature deal that helps her net worth exceed an estimated $3 million.

This is what has come into a league where giant endorsement deals are rare, and fewer than 25 players make a salary of at least $200,000.

Can U.S. fans find a place for the women’s game?

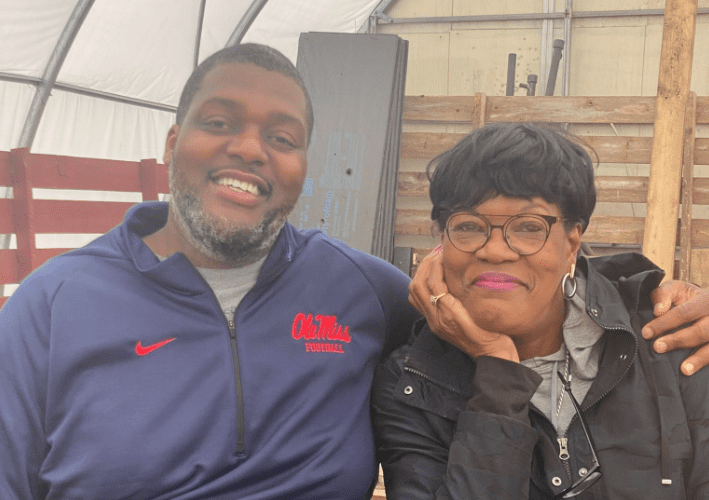

A few months before March Madness, Ole Miss coach Yolett McPhee-McCuin called out the Oxford community for not attending the Rebels’ games.

“The Oxford community needs to catch on. The Ole Miss campus needs to catch on. There are (women’s) games that are sold out. The ticket for the LSU-South Carolina game was $3,000. It’s disappointing when my team runs out here and has won a whole lot, and we don’t get the crowd support that we deserve,” McPhee-McCuin said after an 80-75 win over Florida drew fewer than 3,000 fans.

“When I turn on the TV, when I look around, when we go to other places, women’s sports is a real thing. I’m going to be the voice for that here because our community needs to be better, man.”

The problem with attendance for the Rebels, and most women’s teams, are over-extended fan bases that have historically gravitated toward men’s sports. There’s limited time, limited resources, and inertia.

Yes, it’s largely affordable to attend an NCAA women’s game. You can get a general admission season ticket at Ole Miss for $50.

For most fans, the problem is not that the product is unappreciated. Fans who are accustomed to watching bone-crunching hits on the gridiron, towering shots over the right field wall, and monstrous dunks on the hardwood, may simply not have the time or money to add a new sport to their rotation. Then it becomes a question of which sport to give up in order to prioritize women’s basketball.

If fans, many of whom live out of town, have already driven in once or twice in a week, will they drive in again?

Most will not.

Those who do, will likely do that only for a special season or big game. That’s candidly also true of some men’s sports. Football may be the only real outlier, but even then, stands are sparse when no-name opponents come to town.

And if you’re not attending games in person, you’re less likely to be emotionally engaged enough to watch on television. You don’t know the players, and it becomes just another basketball game on your device.

For most schools interest increases if the women’s basketball team wins at a high level. It’s different than football. There’s a culture of celebration around football with tailgating, with alumni returning to campus, with family and holidays. If a football team is bad fans are mad. If the women’s basketball team is bad fans are indifferent.

It takes sustained high-level success to build a tradition like that at UConn or Tennessee or like South Carolina appears to be building now.

Or it takes a special player to pass through your program, one who hits logo 3s and draws comparisons to the most accomplished men’s basketball player, Pete Maravich.

That player is very interesting.