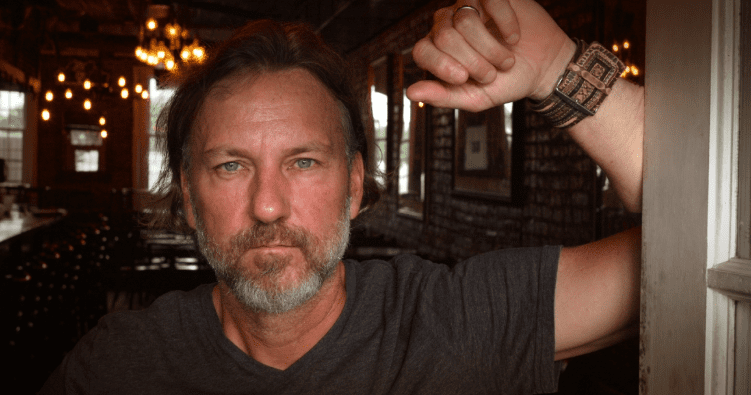

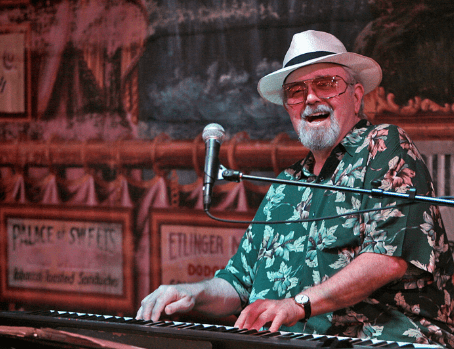

- The Foxworth native was back in his home state as a Governor’s Arts Awards honoree.

The highlight on a whirlwind day of high points for country, blues and rock ‘n’ roll pianist Earl Poole Ball didn’t come on stage at the recent Governor’s Arts Awards in Jackson, where he accepted a Lifetime Achievement Award, but from the very un-rock ‘n’ roll floor of the Mississippi Senate.

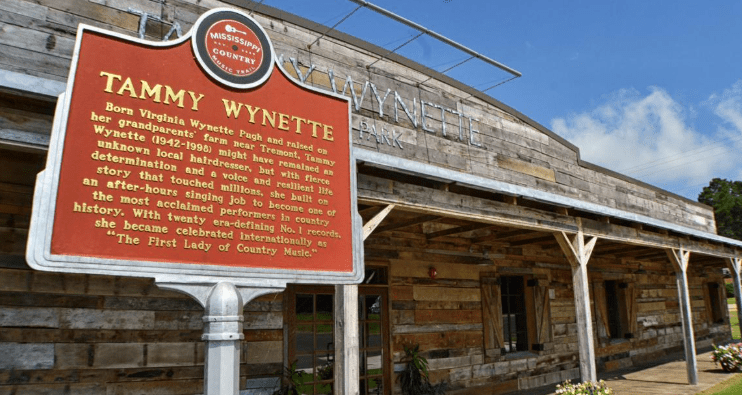

Winning top honors from his home state after decades of playing music with artists like Johnny Cash, Carl Perkins and Merle Haggard—that’s one-half of the Million Dollar Quartet, plus one pioneering country-music outlaw—was more than he could have dreamed as a kid in Foxworth.

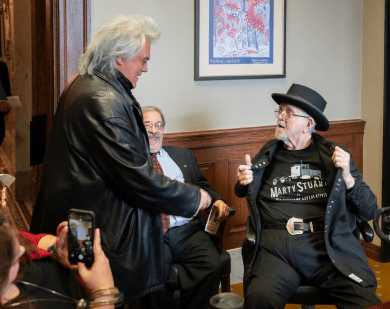

An unscripted reunion with one of his old friends made the day even more special.

“We were all there at the Senate, and here comes my buddy Marty Stuart, a total surprise to me, and he gave me a big ol’ hug,” says Ball, who happened to be wearing a Marty Stuart T-shirt on the occasion.

The pair first met when Stuart joined Cash’s band in 1980, and they became fast friends based on their Mississippi connection. They have remained close over the years.

That night, during his showcase performance, Ball collaborated with Hill Country bluesman Cedric Burnside, who won the Excellence in Music honor. But today, a couple of weeks shy of his 83rd birthday (it’s March 12), Ball is resting at his Austin, Texas home, recovering from minor surgery and reflecting on the good will he received from his home state.

“It was greatly gratifying,” he says, “and it touched me down deep in my heart to feel that I was remembered way back down there on those little red clay hills.”

Ball’s story begins at the Foxworth First Baptist Church, where his aunt Kathryn Ball taught him to play piano. He then landed a gig on “The Jimmy Swan Show,” a local television program based in Hattiesburg, hitchhiking the 50 miles both ways every week. When he was 20, his father gave him three $100 bills and a bus ticket to Houston, where he could pursue music on a larger scale.

Ball quickly fell in with like-minded country artists such as Mickey Gilley and Glen Campbell, who would sit in with Ball’s band regularly, and honed his musical chops playing five nights a week. During the day, he sold sewing machines to finance his next move—Los Angeles, home of both the music and film industries, where he could pursue both of his dreams.

“After four years, I left town and drove my own paid-for automobile, and had another three or $400 in my pocket to get me to California so I could try to get a job with NBC.”

Ball had a couple of friends already in L.A.—Eddie Hodges, whom he first met in Hattiesburg, and Dick Stubbs, a steel guitar player who sold sewing machines for the same company Ball worked for—and they helped him get involved in the music scene. Soon, he had a regular live gig and was logging time in local recording studios, too, thanks to his new friend Gram Parsons. The singer hired Ball to play on the 1966 album Safe At Home from his group the International Submarine Band, and then played with him again on Sweetheart of the Rodeo, the country-rock classic from the Byrds, in 1968.

Another Mississippi native, bassist Chris Ethridge from Meridian, was also part of Parsons’s orbit. They connected at a barbecue, but by the time Ethridge and Parsons formed their next group, the Flying Burrito Brothers, Ball had joined the staff of Capitol Records, where he produced the Merle Haggard album Tribute to the World’s Best Damn Fiddle Player (Or, My Salute to Bob Wills).

All the while, Ball maintained his music gigs to pay the bills, but his true passion at the time was cinema. When he couldn’t break into Hollywood as a producer or actor, though, he leaned back into his musical skills and began writing songs for films. He often worked on films with Peter Bogdanovich, including “They All Laughed,” which starred Audrey Hepburn.

A promotion and transfer to Capitol’s Nashville office moved him further up the food chain, but the corporate side of music left him ready to play again. By 1973, he had begun working with Johnny Cash in the studio, and he joined Cash’s touring band in 1977, where he stayed until health issues led Cash to stop touring in 1997.

“(Cash) was a real fine guy, and he treated me fairly and bought me a white piano to play, and I played it for twenty years,” he says. “And when the show closed, he gave me the piano.

Ball used the opportunity to ease into retirement, himself, after four decades in the music business. If you want to hear him play live these days, you’ll have to visit the Continental Club in south Austin, a blues, country and rockabilly bar known for hosting artists like Stevie Ray Vaughan.

“People come from everywhere and want to take pictures with me and get autographs, and it flatters me and makes me feel good,” he says. “It does my soul good to play music two days a week and no more than that, because I don’t need to try to work [too] hard. I just have to get out and play music and try to enjoy life. It’s hard for an old music man to quit doing music.”