For readers today, Faulkner’s literary reputation probably owes a good deal less to his loyal defense of the American Way than to the lessons we can learn from his penetrating, tough-minded criticisms of his native land.

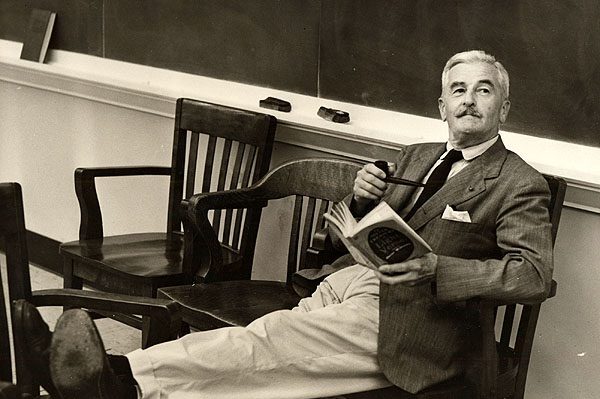

On the sweltering afternoon of July 7, 1962, the town of Oxford, Mississippi, paused to pay its final respects to its most famous native son. Winner of the 1949 Nobel Prize in literature, creator of a dense fictional domain modeled largely on Oxford and Lafayette County, William Faulkner had suffered a heart attack and died early Friday morning, July 6, at Wright’s Sanitarium in Byhalia, Mississippi.

Among those who traveled to Oxford for the funeral was William Styron, a young Virginia novelist much influenced by Faulkner’s work. According to Styron’s moving account of the funeral, which he would publish in the July 20 issue of Life magazine, businesses closed around the town square, and White and Black citizens interrupted their Saturday marketing to crowd the sidewalks. They turned “watchful and brooding faces” toward the burial motorcade as it wound slowly past the courthouse on its way north to St. Peter’s cemetery on Jefferson Avenue, where, in the “monumental heat,” Faulkner would be laid to rest “on a gentle slope, between two oak trees.”

It was a scene worthy of Faulkner’s pen. In fact, his 1942 novel Go Down, Moses ends with a strikingly similar funeral procession, as a hearse bears the body of another native son through the streets of a small north Mississippi town on a “bright hot” July afternoon, passing before an interracial crowd of onlookers “into the square, crossing it, circling the Confederate monument and the courthouse while the merchants and clerks and barbers and professional men . . . watched quietly from doors and upstairs windows . . .”

In the novel, however, the funeral is for a young Black man, an outcast who fled Mississippi for the North, returning home only in death. Faulkner would have appreciated the irony. For much of his literary career, he too had been a kind of outcast, laboring in obscurity over powerful but also notoriously difficult works that were largely neglected by the American reading public. By 1945 he had published thirteen novels, many of them destined to become classics of American literature, but not one of them remained in print in the United States.

Out of Obscurity

Many in his hometown felt that his fictional community of Jefferson, Mississippi, had given Oxford a bad name. But the fact that Life, one of the most popular American magazines of the day, chose to devote a four-page illustrated spread to the funeral in Oxford is clear evidence that, by 1962, Faulkner’s literary fortunes had improved dramatically. Indeed, the publication in 1946 of The Portable Faulkner, a Malcolm Cowley-edited collection of stories and novel excerpts for the popular Viking Portable Library series, began to bring Faulkner to the attention of a wider American readership. And, the commercial success of his 1948 novel Intruder in the Dust, along with its development into a major motion picture in 1949, completely revitalized his career, paving the way for the Nobel Prize the following year.

At the time of his death, he was widely considered the most important American novelist of his generation and arguably of the entire 20th century, eclipsing the reputations of contemporaries like F. Scott Fitzgerald, Thomas Wolfe, and even Ernest Hemingway. His death was front-page news in the New York Times, which quoted a statement by President John F. Kennedy that “since Henry James, no writer has left behind such a vast and enduring monument to the strength of American literature.”

The same issue of the Times devoted two additional pages to Faulkner’s career, including a reprint of his Nobel Prize address, excerpts from his fiction, a bibliography of his major works, and a literary appreciation by the paper’s chief book critic.

Time, Newsweek, The Saturday Evening Post, and other mainstream American magazines joined Life in publishing full-length articles celebrating Faulkner’s life and works.

A wire service report estimated that nearly 10,000,000 copies of the author’s books had been sold during his lifetime.6 Clearly, the days of obscurity were over.

Reputation remains high

Forty years later in 2002, Faulkner’s literary reputation remains as high as it was at his death, perhaps higher. Novels such as The Sound and the Fury (1929), As I Lay Dying (1930), Light in August (1932), Absalom, Absalom! (1936), and Go Down, Moses (1942) have become fixtures in college literature courses, along with short stories such as A Rose for Emily, Dry September, Barn Burning, Red Leaves, and That Evening Sun, which are also widely taught in high schools.

Moreover, a booming critical industry has developed around Faulkner’s work. The Faulkner and Yoknapatawpha Conference, an international gathering of critics and scholars at the University of Mississippi, attracts hundreds of registrants each year. Similar conferences have met with success in France, Germany, and Japan in recent years. Academic journals devoted exclusively to Faulkner can be found in the United States, France, and Japan. Southeast Missouri State University is home to a research center for Faulkner Studies, and the University of Mississippi boasts an endowed professorship in the field. And, according to the Modern Language Association, close to 5,000 scholarly books and articles on Faulkner’s work have been published since the author’s death, more than on any other American writer.

Yearly figures may have declined from the all-time high of 194 publications on Faulkner in 1980, but the 118 books and articles listed for the year 2000 once again place Faulkner first among American authors.

Readers of the 1960s

Readers, then, continue to rank Faulkner among the giants of American literature. They differ from readers of the early 1960s, however, in their reasons for doing so. Every generation views its heroes, villains, and geniuses in its own fashion, through the lens of its specific historical situation, its guiding questions and concerns. In the 1950s and early 1960s, those concerns were shaped above all by the Cold War. The United States was locked in struggle with the Soviet Union and China, a struggle not only over geographical territory (Korea, Cuba, Vietnam) but over political and economic ideas as well: capitalism versus communism and democracy versus totalitarianism.

This generation of Americans found in Faulkner a writer who could be held up to the world as a paragon of American values. It is no coincidence that between 1954 and 1961, under the Eisenhower and Kennedy administrations, Faulkner traveled to eleven different countries in Europe, Asia, and South America, giving interviews and press conferences, often under the direct sponsorship of the Cultural Services branch of the U.S. State Department.

Many of his greatest characters, from Caddy Compson of The Sound and the Fury to Joe Christmas of Light in August, Thomas Sutpen of Absalom, Absalom!, and even Flem Snopes of The Hamlet, are misfits and malcontents who wage a thoroughly American struggle against the limitations of class, gender, or race, or the tyrannies of a repressive social order. Even the lush, idiosyncratic prose style of Faulkner’s stories and novels could be seen as a monument to American individuality and freedom of expression. Moreover, at a time when the threat of nuclear annihilation seemed all too real to Americans, his inclusion of courage and endurance among the “eternal verities” described in his Nobel Prize address must have been especially poignant.

The year of Faulkner’s death, after all, was also the year of the Cuban Missile Crisis, when President Kennedy brought the nation to the brink of nuclear war with the Soviets. We can thus begin to see why Kennedy, who also wrote a Pulitzer Prize-winning book with the revealing title of Profiles in Courage, would praise the “strength” and “enduring” legacy of Faulkner’s works. Like Kennedy, Faulkner was speaking the language of Cold War America.

Readers of today

By contrast, the teachers, critics, and scholars at the beginning of the 21st century, having come of age in the wake of the civil rights and women’s movements, the Vietnam War, and the Watergate scandal of the early 1970s, exhibit a less defensive, more critical (even skeptical) attitude toward American society and its basic beliefs. They are more likely to praise Faulkner not for celebrating them but for challenging American values. These readers seem more attuned than their predecessors to the way Faulkner exposed the failures of responsibility and community that have too often gone hand in hand with American individualism in stories of self-made men like Thomas Sutpen of Absalom, Absalom!, L. Q. C. McCaslin of Go Down, Moses, or Flem Snopes of The Hamlet. Current readers can also place American ideals of freedom and equality against a disturbing historical backdrop of slavery and inequality through Faulkner’s depictions of the plantation system and the color line in the South.

For readers today, Faulkner’s literary reputation probably owes a good deal less to his loyal defense of the American Way than to the lessons we can learn from his penetrating, tough-minded criticisms of his native land.

#####