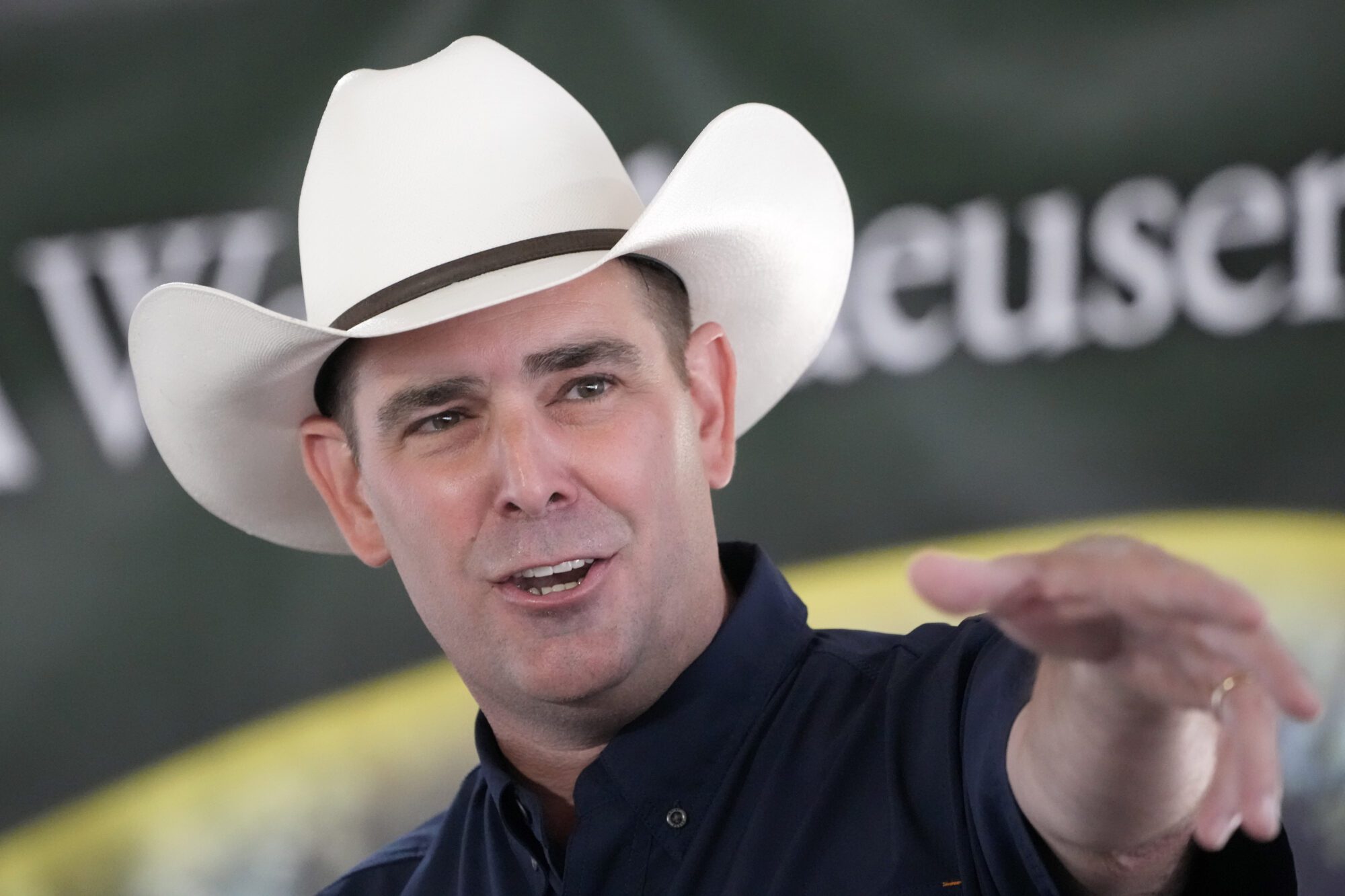

In this photo taken March 10, 2010, Paul Lacoste, a former Mississippi State football player, personal trainer, and main coach of the 12-week "boot camp," held at a private college near the Capitol in Jackson, Miss., calls out exercises to the class. (AP Photo/Rogelio V. Solis)

Efforts to link Gov. Tate Reeves to the TANF welfare scandal through trainer Paul Lacoste are highly speculative at best, and dishonest at worst. What’s more, it’s not clear Lacoste did anything legally wrong.

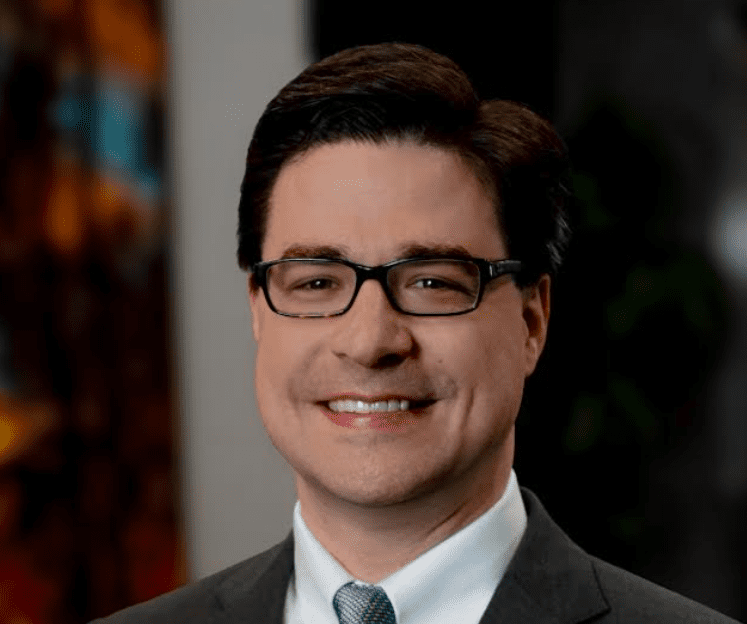

Ninety-five. That’s the number of public Facebook posts by cartoonist and Mississippi Today Editor-at-Large Marshall Ramsey singing the praise of fitness trainer Paul Lacoste.

Ramsey, like many other high profile people, participated in sponsored fitness bootcamps put on by Lacoste, a former Mississippi State and NFL football player. Then-Lt. Governor Tate Reeves was just one of hundreds that cycled through the camps over the years.

Separate from these sponsored bootcamps, Lacoste has become a figure in the state’s TANF welfare scandal, though he denies the claims made against him in a civil suit filed by the state to recoup TANF welfare funds. He’s filed a counterclaim against the state.

To be clear, Marshall Ramsey participating in multiple fitness bootcamps with Paul Lacoste, or gushing effusively over the difference Lacoste made in his life, is not proof that Ramsey was complicit in or condoning of the welfare scandal. Far from it.

But that is precisely the type of guilt by association play Ramsey’s outlet, Mississippi Today, is attempting with Reeves. It clearly wants readers to believe the fact that Reeves participated in some of those same bootcamps is evidence of Reeves’ involvement in the scandal.

The efforts to link Reeves to the TANF welfare scandal through trainer Paul Lacoste are highly speculative at best, and dishonest at their worst.

In their zeal to implicate Reeves, Mississippi Today forgot how words work. Participating in a sponsored fitness bootcamp with a couple of hundred other people does not a “long-time personal trainer” make.

In their zeal to implicate Reeves, the outlet also forgot how time works. The meeting between Reeves and Lacoste that Mississippi Today points to as the “inspiration” for the Lacoste contract at issue in the TANF suit occurred after Lacoste had already contracted with the state to perform the program. Indeed, it occurred after Lacoste had already begun one of the bootcamps under the contract.

Nonetheless, Reeves’ opponent in the race for governor, Democrat Brandon Presley has seized on Mississippi Today’s characterization of the relationship between Reeves and Lacoste to attack the sitting governor in ads. The PAC of the extremist Southern Poverty Law Center has gotten in on the attack action.

What’s more, while there was certainly illegality in the broader welfare scandal–people have pled guilty to crimes–it is not actually clear that Lacoste did anything legally wrong. He’s not been criminally charged and he may yet even be exonerated in Mississippi’s civil suit to recoup funds.

A Long History in Fitness

Paul Lacoste’s business featured two “tracks.” Lacoste conducted classes throughout the year with clients who paid to train with him. Beginning in 2010, he also offered training sessions for state leaders and influencers under “Fit 4 Change” branding.

Over 200 people participated, Republicans and Democrats alike. Lacoste said at the time that he wanted to inspire the state’s leaders to set a positive example for the rest of Mississippi.

House Democrat member John Hines was the biggest loser, with over 70 pounds dropped. His Democrat colleague, Steve Holland would eclipse the mark once the bootcamp finished, shrinking from 359 pounds to 216. Holland, who is known for acerbic wit, quipped at the time “we feel good, I’m even loving Republicans right now.”

The program made national news, with outlets like CNN covering Lacoste’s mission to improve the health of Mississippi.

While these “Capitol” sessions were free to participants, they did not cost taxpayers anything. Third-party sponsors, like the Mississippi Beverage Association and several businesses and associations within the health care industry, paid for the training.

Lacoste would continue the program year-to-year, and expand his offerings to include, among other groups, parents and teens looking to get in shape together, educators, and members of the clergy.

Among the throngs of trainees that participated in the “Fit 4 Change” camps were folks like Ramsey and then-Lt. Governor Tate Reeves.

None of these trainings are tied up in the allegations made against Lacoste in the TANF welfare scandal, but what they do establish is a long track record by Lacoste of supplying fitness trainings that were recognized by lawmakers and Capitol-level influencers as being effective.

Next Level Mississippi

After nearly a decade of providing sponsored fitness bootcamps, Lacoste contends he was approached by state officials about scaling his program outside of the Jackson area to other parts of the state.

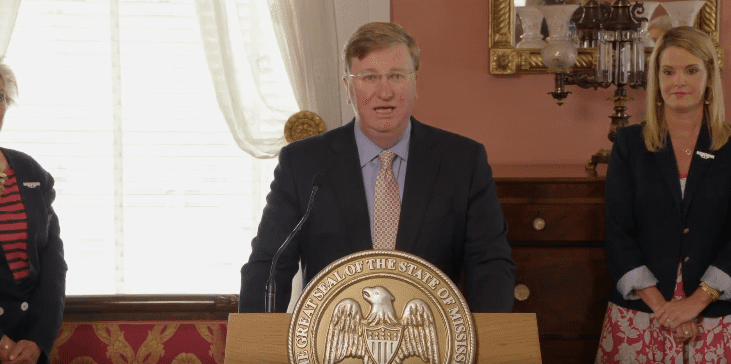

In his counterclaim against the state of Mississippi, Lacoste indicates he was contacted on April 8, 2018 to set up a meeting with then-Governor Phil Bryant and former Mississippi Department of Human Services (MDHS) Executive Director John Davis.

Lacoste claims he attended the meeting, that Governor Bryant and Davis were both present, and that representatives of the federal government were also in attendance. Reeves was not present at this meeting.

According to Lacoste, at this meeting he was asked to provide training services to the state as part of an “initiative to reduce obesity and improve wellness of Mississippians.”

Following the meeting, Davis directed Lacoste to Nancy New and the Mississippi Community Education Center (MCEC), commonly known as Families First. In 2018, Lacoste entered into a fixed services contract with MCEC to provide three fitness bootcamps, one in Pascagoula, one in Brookhaven, and one in Greenville. The program would be called “Next Level Mississippi.”

The first bootcamp in Pascagoula started in January of 2019. A WAPT report on January 9, 2019, announced the start of Next Level Mississippi. The report indicated that the program was being funded by both state and federal dollars, that the funds flowed through a grant by MDHS and Families First, and that the program would provide free training to people who might not otherwise be able to afford it.

Lacoste had originally been due to supply the second bootcamp in the summer of 2019 and the third in the fall of 2019. After the Pascagoula bootcamp, he was asked to accelerate the schedule and perform the second and third camps simultaneously during the summer of 2019.

An April 2019 Daily Leader article in the lead up to the Brookhaven bootcamp again mentioned that the Next Level Fitness bootcamp was being funded by MDHS and Families First. It documented the success of Lacoste’s previous bootcamps in helping Mississippians to lose thousands of pounds.

A June news report from Delta News TV showed video footage of the bootcamp in Greenville and featured an interview with Democratic lawmaker John Hines, who helped bring the program to Greenville.

In mid-summer of 2019, Phil Bryant received notice of irregularities at MDHS. He notified Auditor Shad White, who began an investigation. In July of 2019, John Davis resigned his post and MCEC stopped funding Next Level Mississippi. At the time of Davis’s resignation, Lacoste was midway into the Brookhaven and Greenville bootcamps. His lawsuit against the state claims he finished these bootcamps without compensation owed under the contract.

Tate, the Time Traveler

In August of last year, Mississippi Today fired its first shot over Reeves’ bow in the TANF controversy. Anna Wolfe trained her sights on Reeves in an article entitled “Gov. Tate Reeves inspired welfare payment targeted in civil suit, texts show.”

It was a fairly definitive claim built on demonstrably shoddy evidence. Unfortunately, the exact arguments, with the same exact “evidence,” have now been regurgitated multiple times, most recently in an article on Monday.

In an effort to link Reeves and Lacoste, Wolfe referred to Lacoste as Reeves’ “long-time personal trainer and buddy.” While Reeves did participate in some of the fitness bootcamps, along with Ramsey and hundreds of others over the years, no one attempting to dispense truth would translate this participation into Lacoste being Reeves’ “long-time personal trainer.”

Mississippi Today’s evidence for the “buddy” part came from the fact that Lacoste had sent Reeves ten text messages. Reeves did not respond to a single one. Nor did he post 95 times about how swell Lacoste was. “Buddies.”

But the narrative of Reeves and Lacoste being close is important if the goal is to provide motive for “good ol’ boy” corruption, or to imply guilt by association.

Setting aside the stretch on Reeves’ relationship with Lacoste, the “texts” alluded to by Wolfe do not, in fact, show that Reeves “inspired” the contract between MCEC and Lacoste.

The first message relied upon was not actually a text, but an email from Lacoste to Davis. It addressed a scheduled meeting with Reeves in February of 2019. Mississippi Today’s reporting of the email focused on a single line to argue that the then-Lt. Governor wanted to meet alone with Lacoste and Davis: “Tate wants us all to himself!”

But the actual email is benign. It shows two sets of scheduled meetings, neither of which put Reeves in the room alone with Davis and Lacoste on the afternoon of February 20, 2019.

The email lists multiple participants in two separate meetings, including a bipartisan mix of state senators and Mississippi Beverage Association head Ron Aldridge. The email simply does not establish a clandestine “pow wow” where evil things were concocted.

The second message Wolfe points to was an alleged text from Davis to a staff member two days after the February 2019 meetings with Reeves, in which Davis referred to Lacoste’s bootcamps as “the Lt. Gov’s fitness issue.”

Remember, the meeting at which Lacoste was asked to put on bootcamps statewide occurred in April of 2018, the fixed service contract with MCEC occurred in 2018, there were television reports in early January on the program and its funding, and Lacoste had already begun one of the bootcamps by the time Lacoste and Davis met with Reeves and members of the Mississippi Senate in February of 2019.

Claiming that Reeves inspired the contract based on a meeting that occurred after the contract was in place and being performed, on the basis of an ambiguous text, seems not only to defy linear time, but evinces a reckless willingness to accept any morsel that implicates a political foe.

Lacoste, himself, attributes the state’s decision to hire him to the April 2018 meeting with Governor Bryant, Davis, and federal representatives, not Reeves–an inconvenient, glossed over fact in the flimsy narrative against Reeves.

With respect to the text message highlighted by Wolfe, I say “alleged” because unlike the scheduling email, the “Lt. Gov’s fitness issue” text between Davis and his staffer is not public. Wolfe’s reporting on the TANF scandal has been predicated on being in sole possession of a wide body of emails and text messages.

Without access to the same body of emails and text messages–emails and texts which could have only been leaked by an investigator or an attorney in one of the cases–it is impossible to know the context of cherry picked messages. That the flow of information seems to have stopped, such that the same texts and emails are being rehashed over and over again, might suggest that the source is no longer active in the case.

Mississippi Today’s articles on the supposed link between Reeves and Lacoste have featured heavily reporting on Reeves’ decision to dismiss MDHS attorney and Brandon Presley supporter Brad Pigott from the case.

Don’t Rush to Judgment on Lacoste

There is no doubt that laws were broken in the TANF welfare scandal. People like Davis and New have pled guilty to crimes. Others are facing serious charges.

Unlike many of the other defendants in Mississippi’s civil lawsuit, Paul Lacoste has not been charged with a crime. Unlike other defendants in the suit, Lacoste was actually qualified to provide the services in his contract and did, in fact, provided those services. All three bootcamps were completed.

Lost in much of the discussion over this scandal is the possibility that the state will prevail against some defendants and not others. People might not think TANF funds should be spent on fitness bootcamps, or that Lacoste made too much money under his contract with MCEC, but that is a different analysis than whether or not the bootcamps and the contract were permitted under the law.

To understand that question requires understanding a little about the TANF program itself.

In 1996, Congress created the TANF program to replace another program, Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC). Unlike AFDC and most welfare programs that supply direct cash assistance, TANF works through a block grant to states.

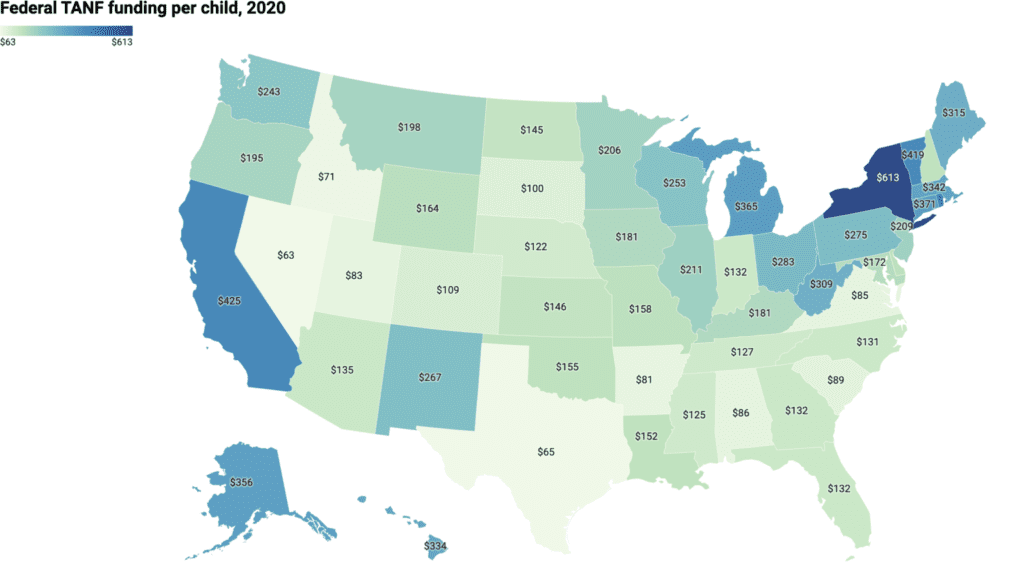

Since 1996, Congress has committed the same $16.5 billion a year to the program. Because of inflation, the real value of the funds declined by 40 percent between 1997 and 2020. That number is much higher given the inflation experienced in the last few years.

States like Mississippi face a second funding challenge. The original formula for the block grants was based on states matching the federal dollars. Poorer states contributed less in matching. That formula is now locked, meaning that there is considerable disparity in federal funding between wealthy states that put up larger matches initially and poorer states that lacked the ability to do so.

In real terms, what that means is that a state like New York gets $613 per child in federal funds through their TANF block grant, while Mississippi received $125 per child.

Because of the limited impact of direct cash assistance of sums like $125, many states have chosen to focus the block grants on trying to remove systemic hurdles that prevent people becoming self sufficient. In 2020, the portion of TANF block grants used for direct cash assistance was just 22 percent. 15 states, including Mississippi, spent under 10 percent on direct cash assistance.

The TANF regulations for how states spend their block grants allow states this leeway. Programs included in state plans are permissible as long as they aim to satisfy one of four conditions:

- Provide assistance to needy families

- End dependence on government by promoting job preparation, work, and marriage

- Prevent and reduce the incidence of out-of-wedlock births

- Encourage the formation and maintenance of two-parent families

There are strong, well-documented links between poverty and obesity. There are strong, well-documented links between obesity and overall health. And there are strong, well-documented links between health and ability to work.

Mississippi has the highest obesity rates, the worst health care outcomes, the highest rates of disability, and the worst work force participation rate in the country. It’s not beyond the realm of possibility that someone could argue that a program to address obesity would provide assistance to needy families or help end dependence on government by promotion job preparation and work.

Wolfe’s initial reporting on Lacoste argued that Davis had instructed his staff to “covertly transfer money to the project.” But if funding for the program was supposed to be “covert,” no one told Lacoste.

As documented above, numerous media reports on the program occurred before the bootcamps were even held. These reports included not only information about the bootcamps, but explicit reference to the source of funding for the camps.

It’s hard to imagine this “covert” funding would have been so non-covertly advertised if Lacoste thought there was anything amiss with it.

Editors Note: Magnolia Tribune Editor-at-Large Frank Corder, like Ramsey, also participated in classes offered by Lacoste.