A decade after the trauma of the 1960s, Oxford settled into the laid-back, picturesque Southern academic backwater it will always be, full of good people with great ideas. The art scene was strong, and the town was full of bright, ambitious young businessmen. Oxford’s flowering of culture in the 1980s was seeded in that time. Those were halcyon years for me, as they were for many other people, and the Hoka was very much a part of it for us all.

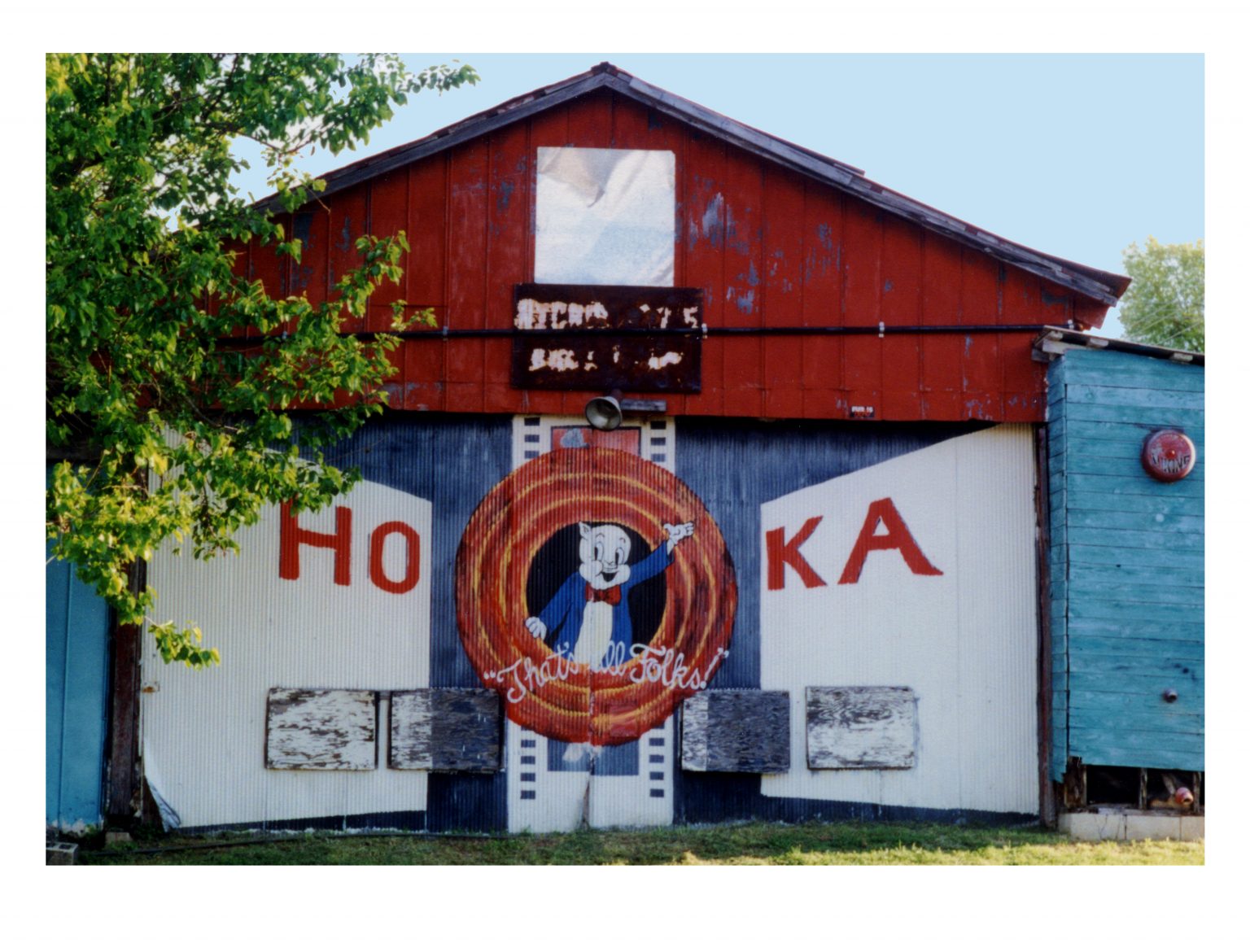

Ron Shapiro opened the Hoka in 1974. The theatre was located across a parking lot from the Gin, the first among many restaurants and bars to open in Oxford after Lafayette County voted wet. The theatre was set up in a long, corrugated building with a walkway that extended perhaps two-thirds its length on the west to street level north. A single door was at that end; midway was a short-roofed porch with a paned double doorway. To the left of those doors was the Hoka logo, a winged Chickasaw princess, painted by a local academic artist. In time, many local artists would festoon the structure inside and out. The bathroom graffiti at the Hoka was as inspirational as it was legendary.

The auditorium seated perhaps 150 to 200 people, though our audiences were usually much smaller. The projection booth was up a short flight of stairs from a tiny untidy office, and the concession stand sold candy, popcorn and soft drinks. We sold tickets from a roll atop what looked like a rough-hewn pulpit at the top of the sloping concrete floor. Inside the projection booth was a table for processing incoming film–checking it for tears, bad splices, twists, or crimps–and the projectors were twin 1936 carbon arc machines, which took a lot of practice with a complex procedure involving levers and foot pedals to switch from one reel to the other. A typical film might be on five or six reels.

I began working at the Hoka in 1977. Typically, in the early days, we’d have two showings, an early movie that started around 6 or 7pm, and a later feature beginning at 8 or 9, depending on the duration of the first. Later we started showing X-rated flicks at midnight, which caused quite a stir at the time, but were very popular and, of course, profitable. Films were rented for three to four days, shipped in bulky hexagonal aluminum containers holding anywhere from one to three reels of 35mm film. Most often they were shipped by bus, and we’d pick them up at the Greyhound station on the corner of 10th and Van Buren, but at times we’d drive to Memphis. Once in the theater, the film had to be checked for tears, mended if needed, and then loaded on our projectors.

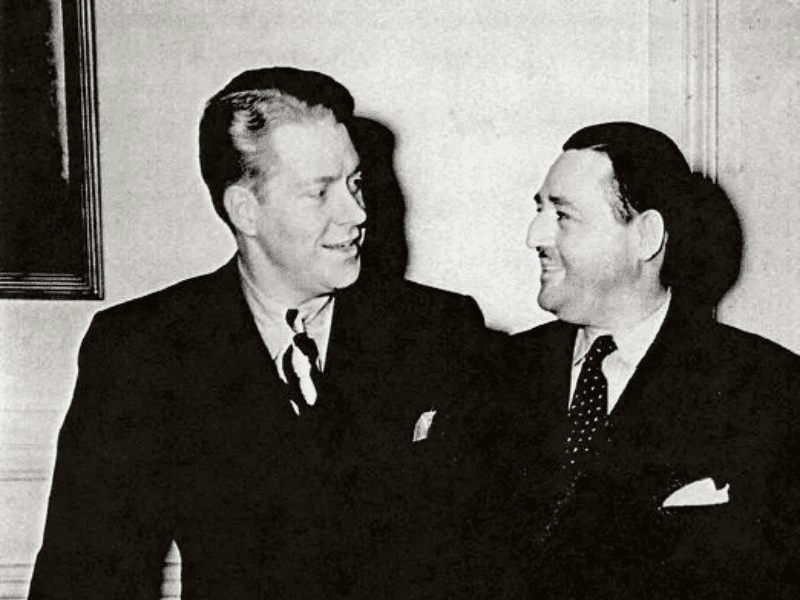

Ron was a good boss. Pay could be erratic, but if I needed money, he’d give me enough to get what I needed or do what I wanted. Ron also taught me a lot, and I do mean a lot, about movies. At that time, in that part of the world, movies were still considered by most people to be nothing more than entertainment, but for Ron, as they were for many others like him who operated small independent “art cinemas” across the country, cinema was the leading art form of the 20th century, as well as a portal to other worlds.

When we first showed The Rocky Horror Picture Show, the audience–and the projectionists, I might add–stared open-mouthed at the screen, and when the audience began throwing rice at the wedding, hollering phrases at the screen and doing the Time Warp, we swept up the rice. We also learned to ban potato flakes. Ron showed a lot of great cult movies by cutting-edge artists like John Waters, Russ Meyers, and William Castle. Several years later, Betty Blair Allen opened the Moonlight Café in the Hoka, and before long, it became a very special sort of place for dinner and a movie.

At a time when film was just coming into its own as an academic medium, Shapiro introduced generations of Ole Miss students to the works of Fellini, Wilder, Woody Allen, Capra, and Chaplain, to name a few, and brought to light (literally) unknown images: Dietrich in The Blue Angel, Lang’s electric automaton in Metropolis, a leather-clad Brando leaning on a jukebox in The Wild One. Ron Shapiro brought film as art to Oxford.

EDITOR’S NOTE: The Hoka closed in1996. Ron Shapiro, who was known as a cultural icon in Oxford, died in 2019.