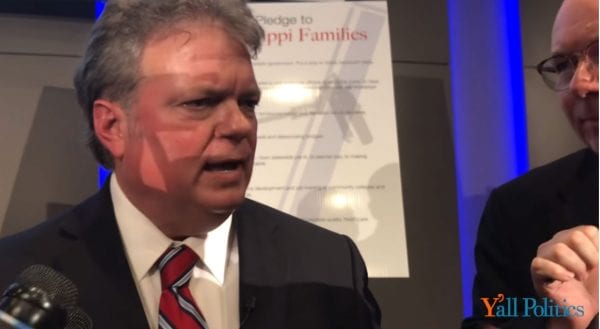

If state Rep. Tom Miles has anything to do with it, the debate over standardized testing in Mississippi public schools is far from over.

Actually, it may expand.

Miles, a Democrat from Forest, has in the past introduced unsuccessful legislation to revamp public school standard testing, most notably an effort to make the ACT the benchmark for graduation.

Miles, a Democrat from Forest, has in the past introduced unsuccessful legislation to revamp public school standard testing, most notably an effort to make the ACT the benchmark for graduation.

He intends to do so again when the Legislature reconvenes in January and hopes to get it over the hump by asking fellow elected officials to declare up-front.

“I want to know everyone’s position that’s running for Governor, Lt. Governor, other state offices and everyone running for Senate and the House, and are they serious about doing something about this testing,” he said.

Mississippi Department of Education officials say that with one exception, they rely on standardized testing required by federal education officials to qualify for the $500-$800 million in education funds the state receives yearly.

Pete Smith, chief of communications and government relations for MDE, said the system is already being tweaked.

“There are things being done to make sure testing is more efficient,” he said. “The one thing we don’t want to do until the feds change something is not do them (conduct testing) since they are a requirement.”

Almost everyone involved agrees this is a complex subject that’s hard to present in a simple fashion to those who haven’t studied the current system exhaustively. And there are crossovers, such as working educators who have spoken out about the current system in the past but are reticent to do so again for career reasons.

Federally-required testing includes assessments in math and English for grades 3-8, Smith said, and “end of course assessments” for Algebra 1, Biology 1 and English 2 in high school. These roughly two-day tests are administered during a three-week “testing window” that began last week.

School districts also administer non-required testing during the course of the school year to determine how well students are learning their course materials.

To qualify for graduation, students must pass the high school tests in addition to the odd duck out, an MDE-mandated proficiency exam in U.S. History that’s required, some familiar with state testing infrastructure say, largely because its been a state requirement for decades.

Miles said he believes all the testing creates a high-pressure environment on students and nudges teachers, whose job reviews are in-part dependent on standardized testing scores, to spend at least some time programming rather than educating.

“They’re programming them to get results because they’re programming them how to take a test,” said Miles, who took training to proctor such an exam this week for a firsthand experience. “And that’s all they’re doing, is showing them how to take a test.

“A lot of these kids, they don’t have life skills because that’s all they’ve been doing, is taking tests.”

Smith said the “end of course” tests are required for graduation, though there are alternate routes for those who fail including: an ACT score of 17 or higher in English, a silver level or above on the ACT WorkKeys skills assessment test, passing the Armed Services Vocational Aptitude Battery (also known as the Armed Forces Qualification Test), or high classroom grades in English combined with standardized test results through a formula.

Smith said the “end of course” tests are required for graduation, though there are alternate routes for those who fail including: an ACT score of 17 or higher in English, a silver level or above on the ACT WorkKeys skills assessment test, passing the Armed Services Vocational Aptitude Battery (also known as the Armed Forces Qualification Test), or high classroom grades in English combined with standardized test results through a formula.

“You do have students who don’t do any of that, and they don’t graduate,” Smith said.

Miles said even if some standardized testing must remain in place to secure federal funds, he would like to see the system simplified to a score of 17 or above for the ACT, especially since the state already spends millions to administer that test to roughly 30,000 high school juniors each year.

However, Smith said, federal education officials view the ACT as a test of broad-based knowledge rather than mandated curriculum.

And then there’s the financial side of the testing debate.

The state is roughly halfway through a 10-year negotiable-cost contract with Questar for standardized testing services of up to $110 million. MDE data shows that the first year of the contract, fiscal year 2016, cost the state $12,346,830.00. That has trended down to $8,697,203.00 for fiscal year 2020. Recently, Questar has come under fire over performance issues and other states are opting to their agreements with the company. Even in the current schoolyear, Questar had major issues causing delays affecting multiple Mississippi districts.

It comes as no surprise that on top of teachers and students feeling over-tested, that the relationship with Questar has been criticized due to data breaches, system glitches and downright failure to perform on test day.

In comparison, the standard cost for the ACT is $50.50/student. Test results are typically available in two weeks and the results have the added benefit of being widely recognized by both academic and workforce training institutions. For the approximately 60,000 combined 11th and 12th graders in Mississippi annually to take the ACT would cost the state just over $3,000,000. States like Florida are giving serious consideration to the role that tests like the ACT/SAT could play in measuring overall student achievement.

Testing costs are on a list of things State Auditor Shad White said he intends to look at in a planned “compliance audit” of MDE in the future. Earlier this month, White issued a report on MDE some have claimed is too critical in which he noted a rise in non-classroom spending statewide over the past several years.

“We constantly need to be reevaluating whether these tests are worth it,” White said. “I’m glad folks are raising the issue in the Legislature and at MDE.”