The Mid-Breton Sediment Diversion is the next in a series of dominoes to fall that ratchets up the threats to Mississippi.

Hurricanes have pounded the Mississippi Gulf Coast often over the last half-century and most Mississippians know that score by the shorthand of the names: Camille, Katrina, Elena, Georges, Ida, Rita and too many others to remember.

Then there were the environmental disasters – the BP Horizon Oil Spill, other pollution threats, the ongoing nightmare of the Bonnet Carre Spillway, and subsequent salinity concerns in the Mississippi Sound. Sprinkle in some difficult government regulations, the impacts of massive global competition and the aging and shrinking of the Mississippi fleet of fishermen, shrimpers and oystermen (and women in all those categories) and the fishing industry in Mississippi faces catastrophic threats.

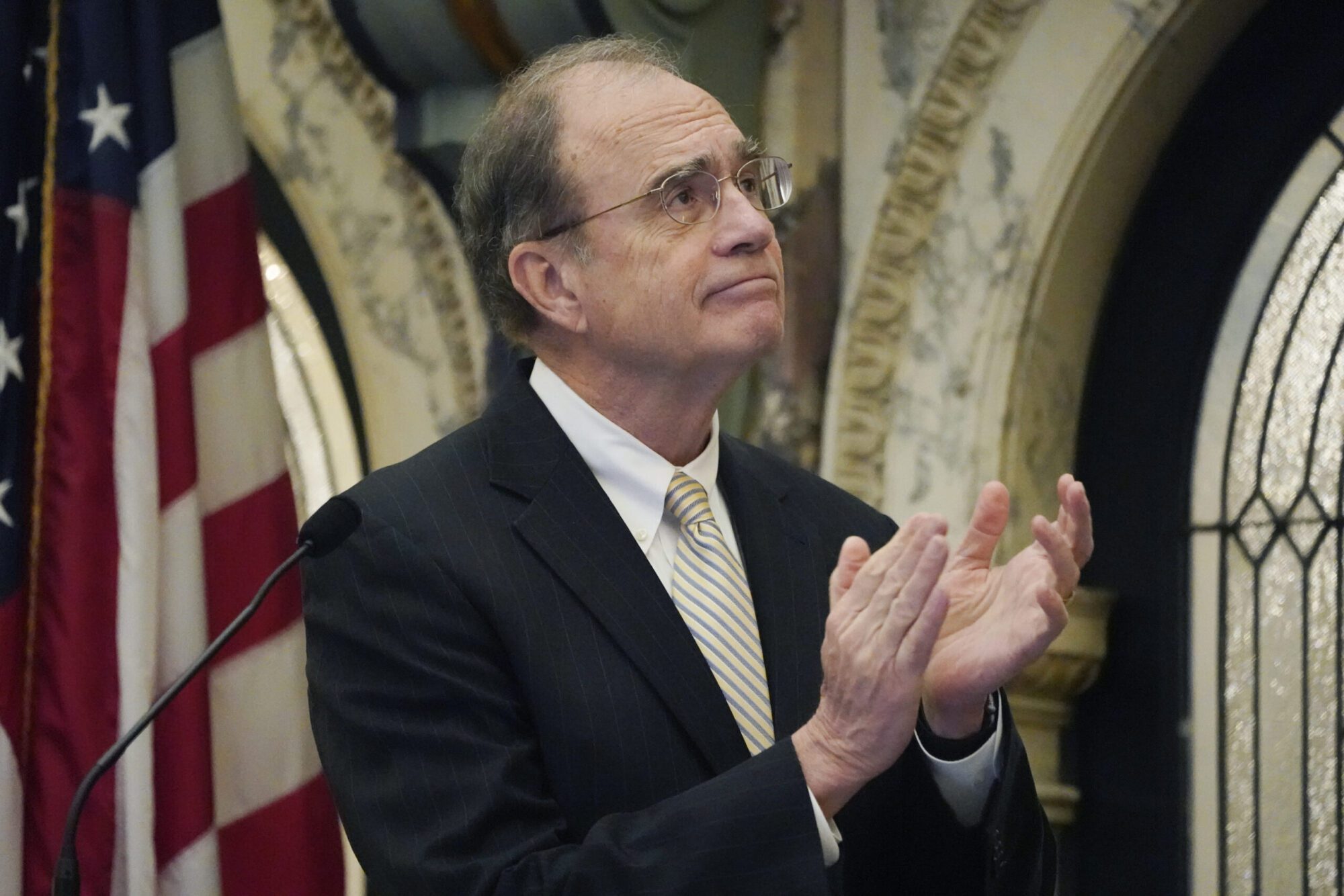

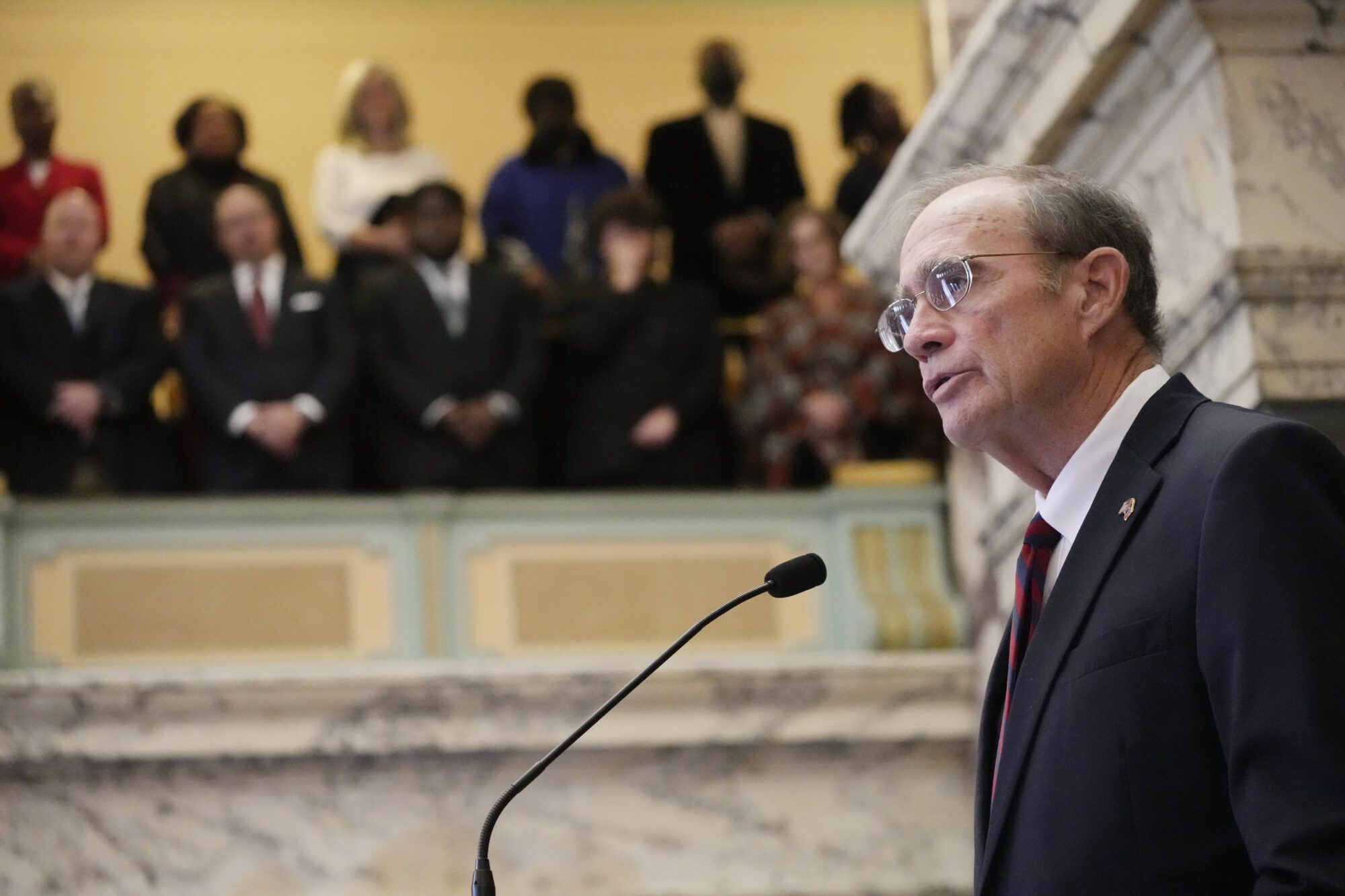

Now comes the sobering but expected results of a new study requested by the Mississippi Department of Marine Resources from the University of Southern Mississippi School of Ocean Science and Engineering researchers working with the Mississippi-Alabama Sea Grant Consortium. Created in 1972, MASGC is one of 34 Sea Grant programs under the auspices of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

Consortium members include Auburn University, Dauphin Island Sea Lab, Jackson State University, Mississippi State University, University of Alabama, University of Alabama at Birmingham, USM, and University of South Alabama.

The study found that a Louisiana Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority plan to divert Mississippi River waters into the Breton Sound through the Mid-Breton Sediment Diversion would essentially obliterate oyster beds in the Mississippi Sound and in doing so impact the ecological benefits of how oysters help maintain and replenish the western and central Mississippi Sound’s eco-system.

Basically, the plan will result in impacts of the Bonnet Carre Spillway releases becoming more or less permanent with both salinity and the chemical content of the diverted waters ultimately impacting in the Mississippi Sound.

The once robust Mississippi fishing, shrimping and oystering industries have seen catastrophic threats for well over a decade. Efforts have been underway in conjunction with the Mississippi State University Extension Service to address those threats through education, information and research.

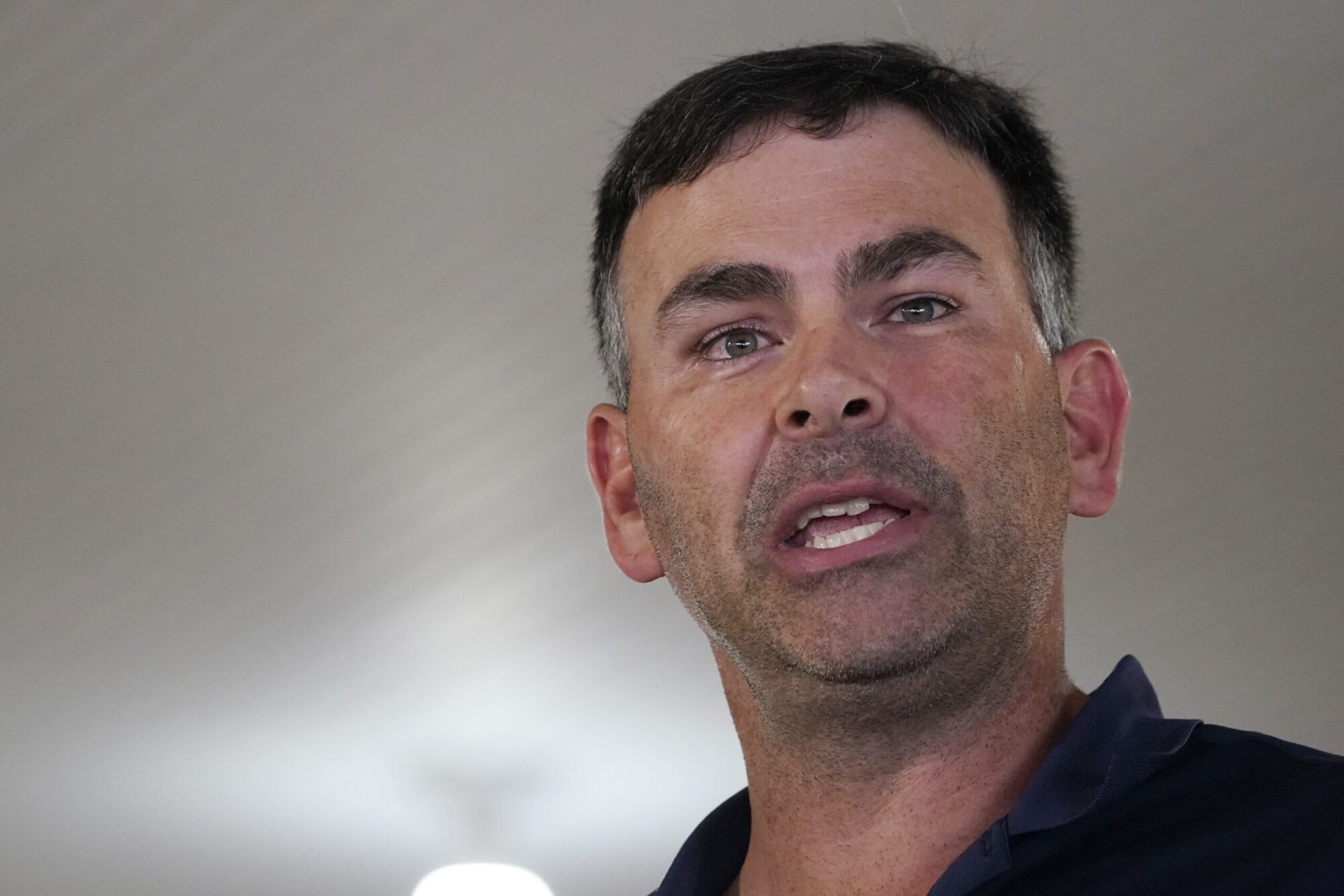

Ryan Bradley, executive director of Mississippi Commercial Fisheries United, told Extension personnel in recent years of the struggles the non-profit organization of Gulf Coast fishing families face.

“This is a proud industry. We work hard. But it is a high-stress profession, and you have to be a thick-skinned person to do this job,” said Bradley, who is a fifth-generation commercial fisherman. “There is a lot of uncertainty in this industry right now and few coping mechanisms when it comes to dealing with the stress. We had over 2,000 shrimp boats 12 years ago; now, we have less than 200. It’s such a volatile business now, that commercial fishermen are encouraging their children not to go into the business.”

The Mississippi seafood industry creates nearly 5,000 jobs and contributes around $250 million to the state’s economy. But Katrina knocked out about half the Mississippi shrimping fleet and oyster harvesting has been severely hampered by storms, the BP oil spill and Bonne Carre freshwater intrusions impacting salinity in the oyster beds and reefs in 2016, 2018, 2019 and 2020.

An MSU Films documentary series “The Hungriest State” (www.msufilms.edu/the-hungriest-state.html) episode offers a comprehensive look at the threats to Mississippi’s seafood industry and for the seafood industry in the wider Gulf of Mexico region.

The dangers aren’t all environmental. Much of it is market-driven as foreign competitors supply well over 92 percent of the shrimp consumed in the U.S. NOAA estimates that between 70 and 85 percent of all seafood consumed in the U.S. is imported.

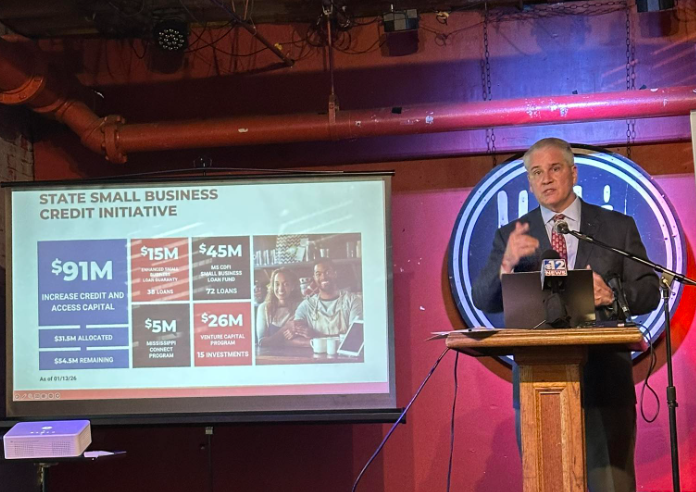

Aquaculture is an important commodity for the state. Mississippi’s aquaculture has risen back to the top, ranking first in the U.S. with some 54 percent of all U.S. catfish produced in the state.

But at this juncture, the Mid-Breton Sediment Diversion is the next in a series of dominoes to fall that ratchets up the threats to Mississippi and U.S. seafood production and the delicate eco-system balance in the Gulf.