Sid Salter

- Columnist Sid Salter writes that observers believe the court could limit the use of race-based legal remedies to protect voters.

Six decades ago, it was evident that the promises of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 would be difficult if not impossible to deliver without passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. The VRA put some teeth in the CRA.

The VRA was particularly strident in the old Confederacy states in which resistance to civil rights and hence voting rights were strongest. In the VRA’s Section 5, it was mandated that any change in election laws and procedures must be subject to “preclearance” by the U.S. Justice Department in advance of implementation. In 1965, “preclearance” was said to be a temporary requirement that would expire in five years.

The original law defined “covered jurisdictions” to include Alabama, Alaska, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, South Carolina, and Virginia. In addition, specific political subdivisions (usually counties) in four other states (Arizona, Hawaii, Idaho, and North Carolina) were also covered.

In 1975, the VRA was extended and expanded by Congress, adding a “covered jurisdiction” formula that had the effect of covering Alaska, Arizona, and Texas in their entirety, and parts of California, Florida, Michigan, New York, North Carolina, and South Dakota. In 2006, Congress extended the VRA for another 25 years.

In 2013, the Supreme Court ruled in Shelby County v. Holder that it was “unconstitutional to use the coverage formula in Section 4(b) of the VRA to determine which jurisdictions are subject to the preclearance requirement of Section 5 of the VRA.” The high court did not rule on the constitutionality of Section 5 itself. The high court said, in essence, that times and circumstances have changed in the U.S.

In the wake of the 5-4 decision of the Supreme Court in Holder that held that Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act was unconstitutional unless Congress retooled it as a national safeguard against the denial of voting rights rather than as a regional safeguard applied primarily in the South. Congress never rose to address that judicial challenge.

The question remains: Was the VRA a vehicle to equal access to the right to vote and the ability to have fair legislative districts drawn, or was it a vehicle designed to guarantee partisan or racial outcomes at the ballot box?

Earlier this month, the Supreme Court heard a Louisiana case that is germane to other key components of the VRA, namely Section 2. As noted in August by judicial writer Alicia Bannon at the Brennan Center for Justice: “The justices will soon decide whether to hear an appeal of an Eighth Circuit ruling that held that Section 2 of the VRA can only be enforced by the Department of Justice — not by individuals or organizations — a decision that broke with decades of practice and would leave many voters unprotected.”

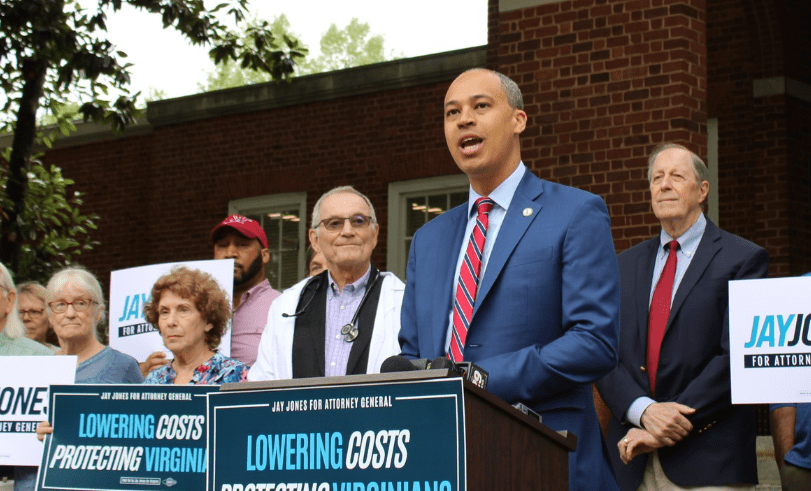

In Louisiana v. Callais, the high court is deciding a constitutional challenge to a congressional district that was drawn to comply with the law’s requirement that election maps give minority communities an equal opportunity to elect representatives of their choice. Observers believe the court could limit the use of race-based legal remedies to protect voters.

Section 2 prohibits minority vote dilution by tactics, legislation, or situations that weaken the voting strength of minorities. Section 2 prevents municipalities from enacting practices designed to give minorities an unfair disadvantage in electing candidates of their choice and has been ruled to be enforceable nationwide.

Another critical 1975 amendment to Section 2 of the VRA provided that proof of discriminatory purpose or intent was not required under a Section 2 claim.

But Supreme Court review of federal VRA protections has resulted in so-called State Voting Rights Acts in nine states (Washington, Oregon, California, Colorado, Illinois, Minnesota, New York, Connecticut and Virginia) and the introduction of State VRA laws in nine other states (Alabama, Georgia, Florida, Texas, Arizona, Missouri, Michigan, New Jersey and Maryland).

The National Conference of State Legislatures reports that such laws don’t address congressional districting but focus on state and local elections on issues that “include requiring preclearance, prohibiting voter intimidation, vote dilution provisions, creation of coalition and crossover districts, private rights of action, and creation of voting-related databases or funds.”