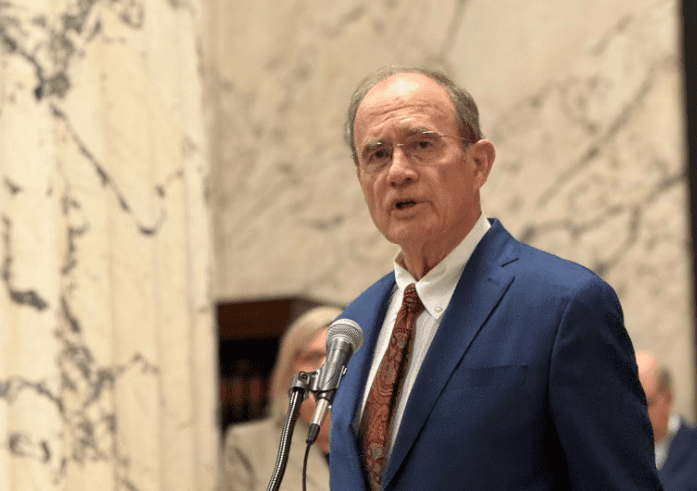

(Photo from Picayune Police Department Facebook page)

- “We’re just as human as everybody else, so we have the same issues and problems everyone has to deal with,” Picayune Police Chief Joe Quave said.

Suicide rates among first responders are statistically higher than those who work in other sectors, mostly due to the stresses first responders experience as part of the profession.

“Honestly, we’re probably more likely to have to deal with it just through dealing with all the problems of the world, plus we have our own,” Picayune Police Chief Joe Quave told Magnolia Tribune. “We’re just as human as everybody else, so we have the same issues and problems everyone has to deal with.”

While on duty, first responders regularly find themselves arriving to scenes much of the general population would never want to set eyes on.

“We do know that first responders in Mississippi face a unique and heavy burden and experience trauma and danger that most people will never experience,” Mississippi Department of Mental Health Executive Director Wendy Bailey said. “The repeated exposure, combined with the pressure to stay calm and act decisively, can take a significant toll on mental health.”

Statistics outline the disparity

These contributing factors are why first responders made up about one percent of all suicides recorded by the National Violent Death Reporting System between 2015 to 2017.

A study on that data found that out of the 61,579 people who died by suicide in the United States, 676 were classified as a first responder. Of those 676 deaths, 58 percent were law enforcement officers, 21 percent were firefighters, 18 percent worked in the EMS field, and 2 percent worked in dispatch.

“In other words, LEOs were 54 percent more likely to die of suicide than all decedents with a reported occupation,” the report states.

The study determined those with prior military service were more likely to suffer from the adverse effects of being a first responder, which include depression, anxiety and post-traumatic stress, to name a few. They are also more likely to use a firearm for their final act.

“Among first responder suicides for whom circumstances were known, intimate partner problems, job problems and physical health problems were most frequent,” the study noted.

To add fuel to the fire, first responders are less likely to talk to someone when they are dealing with life’s difficulties that are compounded by the stress of their occupation.

“Many first responders in our state feel they must always be tough and may be concerned about judgement or career consequences if they admit they are struggling,” Bailey described. “By normalizing conversations about mental health, and creating systems of support, we can literally save lives.”

Help is on the way

Suicide prevention for the general public has been a long-standing priority for the Mississippi Department of Mental Health. As part of that effort, the state joined the nation’s 988 suicide hotline in 2022 to help the general public deal with thoughts of suicide.

Each year since, Mississippi’s call center has continually reported an increase in call volume.

Bailey reports that calls to 988 increased 12 percent year-over-year to more than 17,000 calls this fiscal year.

While first responders also have access to 988, the state of Mississippi recognizes the unique positions those responders are in. As such, officials have been working to provide additional support systems.

“We understand the importance of suicide prevention efforts with our first responders in the state,” Bailey said. “Because of this, several years ago, we developed a specialized training for our Shatter the Silence program for suicide prevention specifically tailored to first responders and law enforcement.”

Last fiscal year, more than 80 officers completed Shatter the Silence, Bailey added.

Another program being implemented as part of legislative action is the Mental Health First Aid for Public Safety training.

Bailey said that last year 1,111 first responders participated in that training, and they are expanding the program.

Chief Quave described how his department is in the planning stages of holding two training sessions for Mental Health First Aid for Public Safety later this month. In addition to his own officers, he said officers from the area will be invited to participate. It will be another of several layers law enforcement agencies can utilize to identify and provide support for their fellow men and women.

Another aid Quave’s department currently utilizes is the Peer Support Program, which trains officers to recognize the signs of stress and mental health issues, and then provide an empathetic ear. Picayune’s municipal law enforcement agency has seven officers trained in that program. The Chief added that recognizing and addressing mental health in first responders has been a group effort.

“What happens if that doesn’t exist? You go through these things, and it gets bottled up, and then you may deal with it in unhealthy ways that are going to lead to even more problems,” Quave said.

An added layer of suicide prevention for first responders comes in the form of the state’s recently implemented Crisis Intervention Team training.

At the Picayune Police Department, 14 officers are trained in CIT. The training is provided to ensure officers are equipped to determine if a person at the scene of a call is exhibiting signs of a mental health issue. This allows the officers to deal with the situation appropriately in hopes of avoiding escalation. It is a skill set that can be utilized to identify if a fellow first responder is suffering their own crisis silently.

“And even though that’s more geared toward being able to serve the public, there are a lot of things in that training that would serve a dual purpose,” Quave described.

Through these training efforts, officers within the Picayune Police Department, and those in neighboring agencies, have found help during a time of crisis.

“By normalizing conversations about mental health, and creating systems of support, we can literally save lives,” Bailey said. “During our Shatter the Silence and Mental Health First Aid trainings, we encourage first responders to educate themselves and others, have the courage to seek help, be supportive without judgement, and confide in a trusted peer.”

To Bailey, the additional legislative support that resulted in these efforts shows first responder lives matter.

“This is not just about supporting policy, it’s compassion in action,” she said.