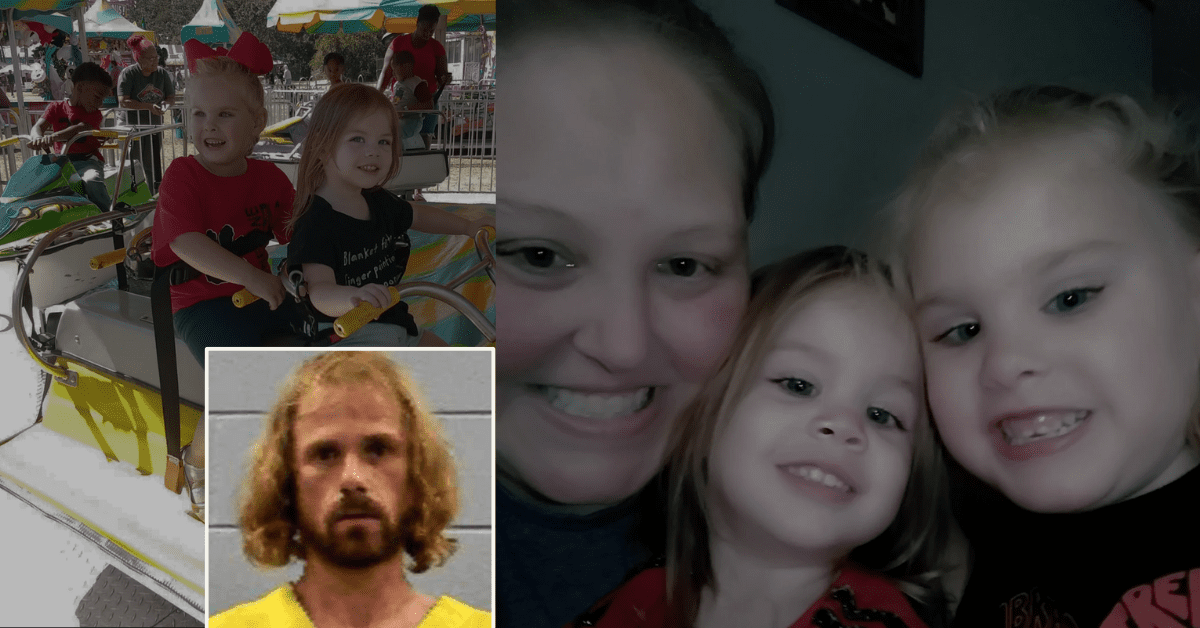

On Friday, 15-year-old Carly Gregg was found guilt of murdering her mother, Ashley Smylie, and attempting to murder her stepfather, Heath Smylie. Gregg, who was tried as an adult in Rankin County, was sentenced to life in prison.

The verdict marks the end of one of Mississippi’s most shocking criminal cases in recent memory. The case captured national attention because of Gregg’s age and the fact that her parents were the targets of her attack, with Court TV televising the highly emotional trial.

The crime took place on March 19, 2024, when Gregg, then 14, fatally shot her 40-year-old mother inside their home in Brandon, Mississippi. According to court testimony, she used her mother’s own handgun, shooting her twice in the face before staging an ambush for her stepfather, Heath Smylie.

When he arrived home, Gregg shot him in the shoulder, but he survived the attack. Prosecutors emphasized that Gregg fled the scene, but was apprehended shortly after near her home, covered in blood.

Video footage from inside the kitchen of the Smylie home captured Gregg moments before and after she shot her mother, and included audio of the fatal shots fired at Ashley Smylie.

Throughout the trial, Gregg’s defense team focused on her mental health issues, attempting to set up an insanity defense. An insanity defense requires proof that a criminal defendant did not understand the nature of the crime committed and cannot distinguish right from wrong.

Dr. Andrew Clark, a child psychologist who treated Gregg, testified that Gregg had been struggling with depression and auditory hallucinations. The defense argued that these issues, compounded by medication that reportedly worsened her symptoms, led to the murder of her mother and attempted murder of her stepfather.

Dr. Clark’s testimony was rebutted by Assistant District Attorney Michael Smith, who on cross examination asked him “You agree that Carly tried to cover up the crime, right?” Clark replied “Yes.” Smith followed up, “If you try and cover up a crime, doesn’t that indicate that you know what you did?” It left the courtroom silent.

Gregg’s defense team, led by attorney Bridget Todd, pleaded with the jury to accept her insanity defense and allow Carly to be sentenced to treatment at Whitfield.

In closing, Todd argued, “Carly didn’t get on the stand and make up a lie that her stepfather had molested her, that her mother knew about it and ignored it and that was the reason that she killed her. She could have got sympathy for something like that but she didn’t do that. Carly just needs help.”

Gregg did not testify on her own behalf and no evidence of abuse of the kind implied by Todd was introduced during trial.

Assistant District Attorney Katherine Newman countered that Gregg’s actions were premeditated. Newman pointed to the fact that Gregg had retrieved the gun from her parents’ bedroom, ambushed her stepfather, and had the presence of mind to flee the scene.

Newman also highlighted chilling evidence from the crime scene, including text messages Gregg sent to her friends after the murder, inviting them to come over and see her mother’s body.

“This was not the result of an uncontrollable mental breakdown. This was calculated, and Carly knew exactly what she was doing,” Newman told the jury.

Jurors deliberated for a little over two hours before returning a guilty verdict on all charges, including first-degree murder, attempted murder, and tampering with evidence.

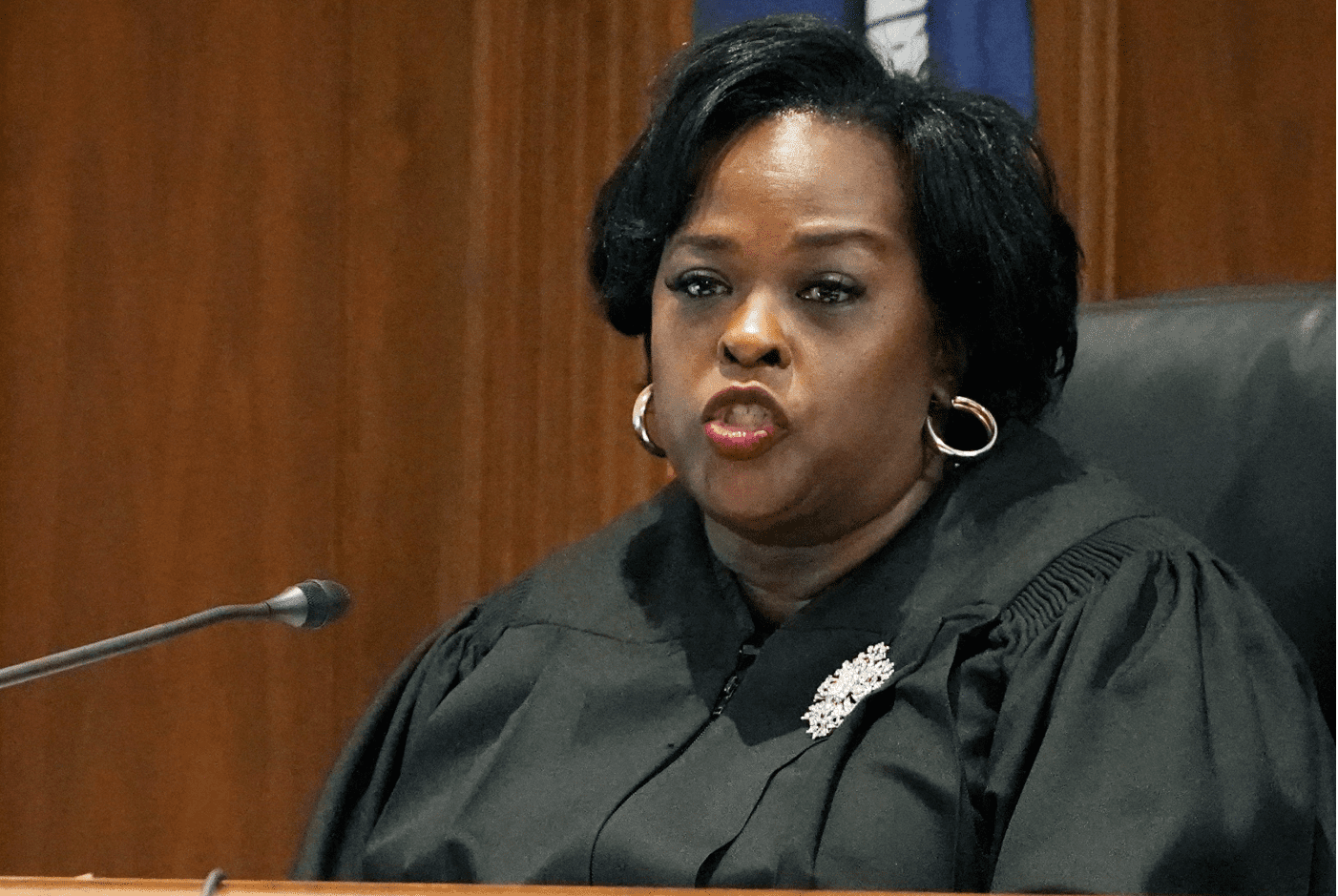

Judge Dewey Arthur then told the jury to resume deliberations regarding sentencing. The jury returned after another few hours and recommended that Gregg be sentenced to life without parole.

ADA Smith told Magnolia Tribune after the verdict that “This was an extremely difficult case. In a case like this, there are no winners. You have a victim whose life was taken by her own daughter and a defendant who, by all accounts, was very bright, but who will now spend the rest of her life in prison.”

Smith continued, “I believe the evidence showed, beyond all doubt, that Carly Gregg committed these crimes and, at the time, knew the difference between right and wrong. The jury’s decisions in both the guilt and sentencing phases confirm that belief.”