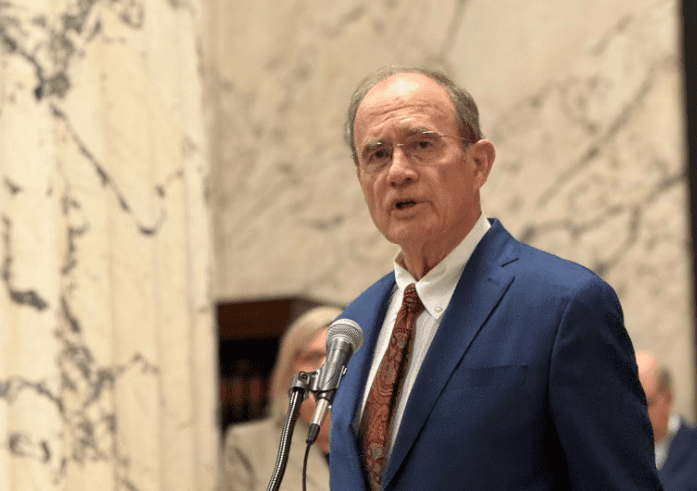

Phil Bryant

- The news outlet contends that the First Amendment’s “reporter’s privilege” allows them to avoid answering discovery in the former governor’s defamation lawsuit. The facts and law are more complicated.

Eons ago, as a young lawyer, I learned an old saying: “When the facts are on your side, pound the facts. When the law is on your side, pound the law. When neither are on your side, pound the table.”

On May 20th, a Madison County Circuit Court judge ordered Mississippi Today to identify sources and produce information related to statements its staff made against former Governor Phil Bryant. The outlet now contends the court order violates its constitutional rights under the First Amendment. It has appealed the decision to the Mississippi Supreme Court.

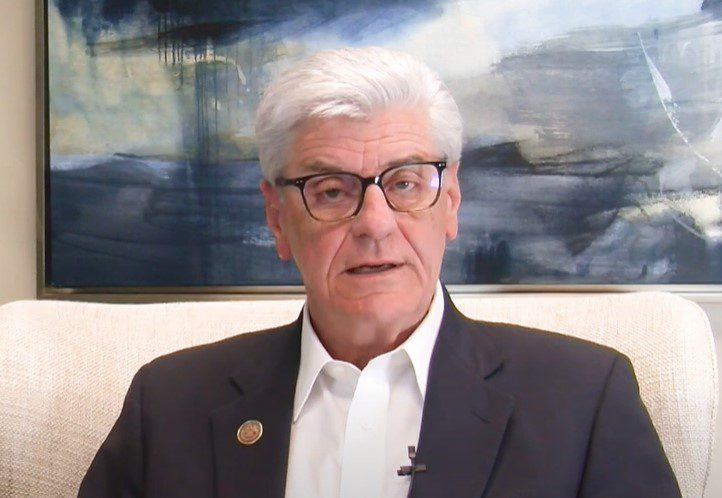

Mississippi Today took the unusual step this week, mid-litigation, of turning to the court of public opinion. In both an editorial and a public statement, Editor-in-Chief Adam Ganucheau denied the outlet had made any false statements, argued the court’s recent order “totally disregards the Constitution,” and presented a rather lofty view of Mississippi Today’s struggle on behalf of journalists, near and far.

The Mississippi Supreme Court’s ultimate decision will not ride, though, on the strength of an editorial, but on the facts and the law — neither of which are as clear as Mississippi Today contends.

A Refresher

Last summer, Bryant filed a defamation action against Deep South Today, the parent company of Mississippi Today, and Mississippi Today CEO Mary Margaret White.

Speaking on a panel at a journalism conference, White had boasted “we’re the newsroom that broke the story about $77 million in welfare funds intended for the poorest people in the poorest state in the nation being embezzled by a former governor and his bureaucratic cronies.”

The TANF welfare scandal occurred while Bryant served as governor. Prior to the filing of his defamation lawsuit, White issued a public apology in which she said:

“I misspoke at a recent media conference regarding the accusations against former Governor Phil Bryant in the $77 million welfare scandal. He has not been charged with any crime. My remark was inappropriate, and I sincerely apologize.”

Bryant’s allegations against Mississippi Today are not limited to White’s comments. A 2022 Impact Report published by Mississippi Today characterized its reporting on the scandal as revealing “former Gov. Phil Bryant’s role in a sprawling welfare scandal,” and delving “further into Bryant’s misuse and squandering of at least $77 million in federal funds.”

Upon winning a Pulitzer Prize for its TANF coverage, the outlet framed its reporting as revealing “for the first time how former Gov. Phil Bryant used his office to steer the spending of millions of federal welfare dollars — money intended to help the state’s poorest residents — to benefit his family and friends.”

Bryant’s lawsuit alleges the statements are false and defamatory. Since initially filing the case, he has added as defendants both reporter Anna Wolfe and Ganucheau. To date, Bryant has not been accused of, charged with, or convicted of any crime in relation to the TANF welfare scandal.

Defamation Law

To prove his case, Bryant is required to show false statements were made with the intent of injuring his reputation. Because he is a public figure, he must also prove something called “actual malice,” which essentially means he must demonstrate the defendants either knew their statements were false, or acted with “reckless disregard” as to whether they were false.

Truth is an “absolute defense” in a defamation case — if a defendant can establish that an alleged false statement was true, the case is over. A plaintiff, like Bryant, is therefore entitled in a defamation case to discover the factual basis a defendant had for making the alleged false statement.

What, for instance, was the factual basis for claiming Bryant embezzled $77 million, that he misused and squandered that money, or that he steered it to family members? Were these statements made up, were they supported by witnesses, or were they supported by documentation?

Since a plaintiff in a “public figure” defamation case is also required to present evidence of the defendant’s mental state, proof of a statement’s falsity is not enough.

If a defendant’s alleged false statement was based on information received from another person in a “public figure” case, the identity of that person becomes relevant.

- Was the person a known enemy of the plaintiff?

- Did they have some self-interest in damaging the reputation of the plaintiff?

- Did they present with sufficient information to be believable?

- Did they have a history of making untruthful statements?

The Fifth Circuit has said “frequently, proof of actual malice will depend on knowing the informant’s identity, because the plaintiff will have to show that the informant was unreliable and that the journalist failed to take adequate steps verify his story.” Sources could also be relevant to show that a defendant was given information that put the defendant on notice that their statement was false or not well-founded before saying it.

Similarly, contemporaneous communications could be relevant in establishing actual malice. An email or text message that read “let’s take this guy down,” could certainly be evidence of motive in a defamation case. So too could notes or previous drafts of documents that demonstrate doubts as to the truth of what was ultimately said or put in writing, or which exhibit personal animus toward the target of the alleged false statement.

In the context of news reporting, for instance, a story originally drafted with a benign headline that is re-written to include an unfounded accusation could be evidence of actual malice.

These are the types of questions a lawyer advancing a defamation case would want to answer. The customary way to make those determinations would be through written discovery and depositions.

The Reporter’s Privilege

In a case involving a news outlet, there are countervailing public interests. Reporters serve an important function in holding government accountable. To do that well, and obtain information the public needs to know, often requires protecting the identify of sources with sensitive information. However, this protection does not operate as an absolute shield in legal proceedings, nor does it exist to wholly insulate any media outlet from engaging in libel or defamation.

The U.S. Supreme Court has never found an unqualified “reporter’s privilege” to protect disclosure of sources or a newsroom’s internal process in the Constitution. In fact, it declined to do so in the 1972 case of Branzburg v. Hayes. The Branzburg Court found that the First Amendment does not protect a journalist from having to identify a confidential source or produce confidential information to a grand jury.

In the 1979 case of Herbert v. Lando, the U.S. Supreme Court similarly found no “reporter’s privilege” under the First Amendment that would prevent a person alleging defamation from “inquiring into the editorial processes of those responsible for the publication where the inquiry will produce evidence material to the proof of a critical element of the plaintiff’s cause of action.”

Some states have enacted what are called “shield laws” to recognize the reporter’s privilege. Mississippi is not among them. The Mississippi Supreme Court has also never considered a reporter’s privilege case, making this appeal what is called “an issue of first impression.”

While the state’s highest court has never considered the issue, federal courts and the 5th Circuit Court of Appeals have. In the landmark case of Miller v. Transamerican Press, the 5th Circuit found some protection for a reporter’s confidential sources. The Miller Court introduced a three-part test for when a reporter could be required to identify his or her sources:

- Is there evidence that the challenged statement is both untrue and defamatory?

- Can the identity of the informant be determined through alternative means?

- Is the knowledge of the informant’s identity necessary or critical to the proper preparation and presentation of the case?

This analysis is fact intensive, and depending on how far into discovery the parties are in Bryant’s case, may require additional discovery to decide. The plaintiff in the Miller case filed a defamation lawsuit against a news organization for reporting that he had misused $1.6 million in union money. Applying its three-part test, the court in Miller ultimately required Transamerican Press to reveal its source.

The Miller court said, “we hold that a reporter has a First Amendment privilege which protects the refusal to disclose the identity of confidential informants, however, the privilege is not absolute and in a libel case as is here presented, the privilege must yield. As the Supreme Court observed in Herbert v. Lando: ‘Evidentiary privileges in litigation are not favored, and even those rooted in the Constitution must give way in proper circumstances.'”

Notably, the Court in Miller and in subsequent Fifth Circuit cases treated requests for internal editorial process — communications, drafts, and so on — as having even less First Amendment protection than confidential sources based on the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in Herbert v. Lando. This means a court adopting Miller’s three-part test to deny disclosure of a source could simultaneously require disclosure of documents related to the outlet’s internal editorial process.

Courts also have tools available to protect sensitive information, including “in camera” reviews –private viewings of evidence by a judge — and protective orders that prevent disclosure outside of the litigation.