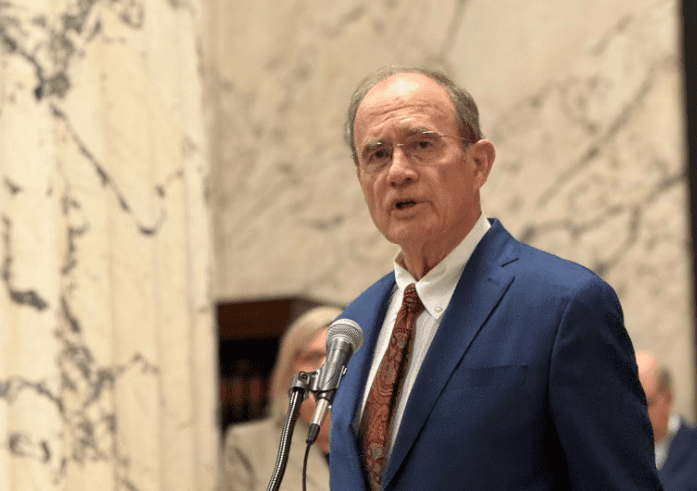

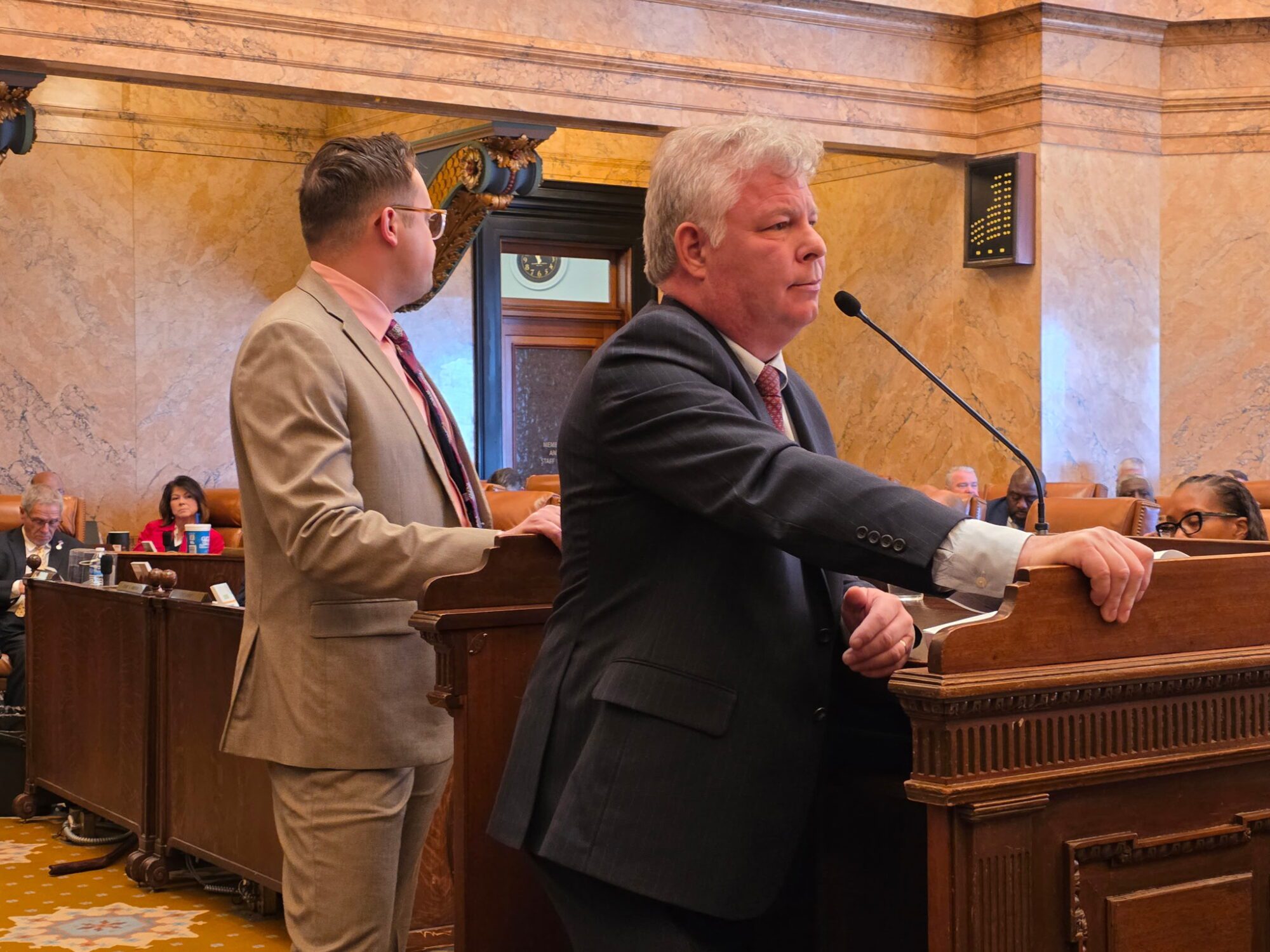

Senate conferees on Medicaid expansion legislation.

On Tuesday, conferees from the Mississippi House and Senate met publicly to see if they could iron out differences to expand Medicaid to able-bodied adults.

Both chambers have proposed plans that would result in the exact same groups of able-bodied adults having access to taxpayer-provided health insurance. The Senate plan comes in at a lower annual cost for the long haul. The House plan carries a one-time federal sweetener.

Understanding the Chambers’ Proposals

Heading into the public conference, the House had proposed a plan to fully expand Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act, up to 138 percent of the Federal Poverty Level (FPL) for a new class of recipients (able-bodied adults). Its plan was not contingent upon the approval of a work requirement.

The Senate took an arguably more conservative tack, proposing to expand only up to 99 percent of FPL to close the “coverage gap” — a phrase historically used to describe able-bodied adults who are eligible neither for Medicaid nor a subsidized private plan on the ACA exchange. The Kaiser Family Foundation estimates there are 74,000 Mississippians in the coverage gap. The Senate made its plan contingent upon a work requirement.

The stated logic behind the Senate’s focus on only closing the coverage gap is that able-bodied adults earning between 100-138 percent already have access to fully-subsidized private health insurance plans on the ACA exchange. Indeed, according to the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), 181,844 Mississippians in this income range are enrolled in a private plan on the ACA exchange.

To put a fine point on the numbers, by a more than 2:1 ratio, the people who would be added to Medicaid under full expansion already have private health insurance through the exchange.

According to Jonathan Ingram at the Foundation for Government Accountability, residents of every county in Mississippi currently have access to at least one private plan on the ACA exchange with $0 premiums, $0 in deductibles, and $0 in co-pays for doctor visits and generic prescriptions. The state currently has no financial liability for these plans.

If the plan originally passed by the House became law, the ACA exchange population would become ineligible for federal subsidies and would be shifted to Medicaid. The state would lose out on over $1 billion in federal payments annually, a fact largely ignored in the pro-expansion economic impact analyses, and by almost everyone in the media.

A Proposed Compromise

House conferees presented a compromise Tuesday that recognized the risk of moving up to 181,844 people off of the ACA exchange’s private health insurance plans. The proposed “middle ground” was to leave people earning between 100-138 percent of FPL on the ACA exchange, but bring the exchange participants under the Medicaid program — essentially to use Medicaid dollars to purchase the ACA exchange plans, similar to the Arkansas model.

(There is an argument that the Senate plan was the “middle ground” between conservatives who are opposed to Medicaid expansion and the House plan to fully expand.)

With the House’s compromise offer, both the House and Senate have proposed the exact same categories of coverage:

- Traditional Medicaid for able-bodied adults earning up to 99 percent of FPL; and

- Private plans on the ACA exchange for able-bodied adults earning between 100-138 percent of FPL.

The only difference then is who would be responsible for administering and paying for the ACA exchange portion. Under the Senate’s plan, the federal government remains responsible for 100 percent of the cost of the ACA plans. The federal government also carries the administrative burden of determining income eligibility/work status.

Under the House plan, the federal government would be responsible for 90 percent and the state would be responsible for the other 10 percent. The state would also become responsible for determining income eligibility/work status for this massive population, resulting in additional staffing and administrative costs.

On an annual basis, the Senate plan is less costly than the House compromise plan for the same coverage. At some level this is intuitive. The biggest expense for expansion, by far, would be between 100-138 percent of the FPL since that’s where the vast bulk of potential new recipients is. The House’s plan would cover 10 percent of this expense, plus administrative costs. Under the Senate plan, the federal government would continue to pick up the whole tab.

At the close of yesterday’s meeting, Senate Medicaid Chairman Kevin Blackwell seemingly communicated that it was unlikely the Senate would accept the House’s offer and asked the House conferees to accept the Senate’s existing plan.

Breaking Down Annual Cost

The math at play is at once simple and complicated. It is simple because the equation is not difficult. It’s complicated by the many unknowns. Economic analyses are only as good as their assumptions and inputs. Garbage in, garbage out.

- How many people will be added under each plan? No one can say for certain. The Senate’s plan has a more natural cap on the population since it only goes up to 99 percent of the FPL and requires recipients to work. The Hilltop Institute, relied upon by the House, estimates 197,000 people will be enrolled under the House’s compromise plan. Notably, The Hilltop Institute previously estimated that the House’s full expansion plan would only result in adding 134,000 people to the rolls. Previous estimates by Kaiser and Commonwealth Foundation have put the number at approximately 230,000 for full expansion. There are 255,844 people when the estimated coverage gap and those CMS says are enrolled on the ACA exchange within the relevant income range are combined. That’s before you consider the population of people that are eligible for the ACA exchange that have not yet enrolled and the people on employer-sponsored plans that will be dropped if Medicaid becomes available to employees. What is certain is that in all 40 states that have expanded, actual enrollment far exceeded projections.

- What will be the cost per enrollee for the traditional Medicaid segment? Two different numbers have been supplied to legislators by the Division of Medicaid and Department of Insurance ($6,912/year v. $8,700/year). Both the Senate and the House used a number in the middle for their internal calculations ($7,998 for House and $7,800 for Senate).

- What will be the cost per enrollee for the ACA exchange segment? Data gathered from the Arkansas Division of Medical Services’ most recent quarterly report puts the number at $8,928/year. The Hilltop Institute used an estimate of $11,357/year.

To account for all of these different inputs, separate analyses of the 0-99 percent population and the 100-138 percent population have been performed below using the full range of potential enrollment and costs that have been presented to the Legislature.

A. The Net Effect

In the best case cost scenario presented below for both the House’s compromise plan and the Senate’s plan (lowest number of enrollees at the lowest estimated cost per enrollee), the state’s annual share would be:

- House Plan: $152.6 million

- Senate Plan: $63.6 million

In the worst case cost scenario presented below for both the House’s compromise plan and the Senate’s plan (highest number of enrollees at the highest estimated cost per enrollee), the state’s annual share would be:

- House Plan: $324.4 million

- Senate Plan: $176 million

It should be noted that my worst case scenario below was only 20 percent above estimate. Many states have experienced significantly higher overruns, in the range of 50 percent.

B. A Closer Look at the 100-138 Percent Bracket

The chart below shows the expense of the House plan to roll the ACA exchange into Medicaid. The costs of each enrollee is the range between Arkansas’ quarterly report and the estimated figure used by The Hilltop Institute. The state’s match would be 10 percent, assuming CMS were to approve the plan as providing for full expansion.

| Enrollment | Cost Per Enrollee | State Share | Total State Cost |

|---|---|---|---|

| 140,000 (Department of Insurance) | $8,928-$11,357 | 10% | $125-159 Million |

| 181,844 (CMS) | $8,928-$11,357 | 10% | $162.2-$206.5 Million |

| 218,213 (20% Above CMS) | $8,928-$11,357 | 10% | $194.8-$247.8 Million |

Under the Senate plan, the state would take on none of the financial liability for subsidizing individuals on the ACA exchange. The federal government would continue carrying 100 percent of the tab — meaning the Senate plan would create $0 in liability for this income bracket.

C. A Closer Look at 0-99 Percent

Because the Senate’s plan does not commit to full expansion, it would not receive the enhanced federal match of 90 percent for this bracket of recipients. Our existing 23 percent state share would be used for partially expanding up to 99 percent of FPL. The House’s compromise plan would receive the enhanced federal match of 90 percent, leaving the state on the line for 10 percent of the cost. For this reason, the Senate’s expense for this bracket is higher, though still considerably lower overall.

Senate Expansion Plan for 0-99 Percent Income Bracket

| Enrollment | Cost Per Enrollee | State Share | Total State Cost |

|---|---|---|---|

| 40,000 (Work Requirement) | $6,912-$8,700 | 23% | $63.6-$80 Million |

| 55,500 (75% of Coverage Gap Enrolls) | $6,912-$8,700 | 23% | $88.2-$111.1 Million |

| 74,000 (Kaiser Estimated Coverage Gap) | $6,912-$8,700 | 23% | $117.7-$148 Million |

| 88,000 (20% Above Coverage Gap) | $6,912-$8,700 | 23% | $140-$176 Million |

House Expansion Plan for 0-99 Percent of FPL

| Enrollment | Cost Per Enrollee | State Share | Total State Cost |

|---|---|---|---|

| 40,000 (Work Requirement) | $6,912-$8,700 | 10% | $27.6-$34.8 Million |

| 55,500 (75% of Coverage Gap Enrolls) | $6,912-$8,700 | 10% | $38.3-$48.3 Million |

| 74,000 (Kaiser Estimated Coverage Gap) | $6,912-$8,700 | 10% | $51.1-$64.4 Million |

| 88,000 (20% Above Coverage Gap) | $6,912-$8,700 | 10% | $60.8-76.6 Million |

The Sweetener & Tricky Accounting

Full Medicaid would also yield a temporary 5-percent bump in the federal matching rate the state receives on its existing Medicaid population for a period of two years. This one-time federal enticement has been used by The Hilltop Institute and others to suggest that full Medicaid expansion could effectively be “free” for the state for the first four years of operation (based on some low ball assumptions on enrollment).

These economic analyses have shown cost and “savings” forecasts limited to 2-4 years. As an example, The Hilltop Institute report produced in support of the House’s compromise plan has a chart on the first page showing “savings” from the plans that only looks at the first two years.

This is highly misleading.

Once a program like this starts, the chance of it ever going away is small. If full expansion occurs, it will not only last for 2-4 years. Supporters of full expansion know that. They anticipate it lasting for decades. And when the one-time money is spent and the “layaway” period is over, the state will have to come up with its share of whichever path it chooses.

One final musing: only in American politics could something that costs billions of dollars be regularly characterized as “free” or “a savings.”