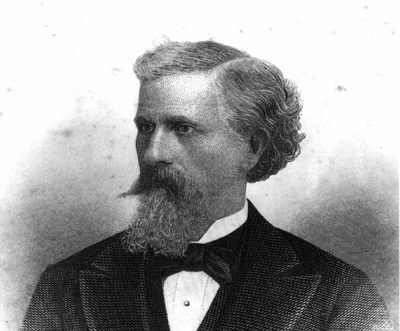

A novelist who also wrote poems, plays, and a travelogue, Falkner himself experienced the topic of his first work: murder.

Likely Mississippi’s most famous literary figure, Nobel Prize laureate and Pulitzer Prize awardee William (Mr. Bill) Cuthbert Faulkner even as a youngster reportedly said, “I want to be a writer like my great-granddaddy.”

William Clark Falkner was that great-granddaddy. Notably, Eudora Welty, Tennessee Williams, and Richard Wright hold equally iconic positions among the “most famous Mississippi authors,” but Great-Grandfather Falkner set the stage for all the followers.

Falkner – lacking the “u” his great grandson Bill Faulkner would return to the family name in 1918 (see this from John Cofield) – moved to Ripley, Mississippi, to seek his fortune at age seventeen; he had been born in Knox County, Tennessee. In the Tippah County town about thirty miles from Elvis Presley’s birthplace, Falkner wrote, and in 1845 published, his first fiction, The Life and Confession of A. J. MacCannon, Murderer of the Adcock Family.

As a twenty-year-old, he entered the Mexican American War (1846-1848), serving as a first lieutenant with the Second Regiment of Mississippi Volunteers. Soon after, he published two more works, The Siege of Monterey: A Poem (1851) and The Spanish Heroine: A Tale of Love And War (1851). Military armed conflict called again; so, he raised a company of men and made colonel in the Second Mississippi Infantry of the Confederate army.

After the Civil War, Falkner returned to Ripley, married Holland Pearce, began practicing law, and turned his energies to business. With military service behind, in 1862 he started the Ripley Railroad Company, becoming a rich man who could afford to devote himself to writing. Five books published from 1867 to 1895: The Lost Diamond, The White Rose of Memphis, Rapid Ramblings in Europe, The Little Brick Church, and Lady Olivia: A Novel.

Writers of Touring Literary Mississippi and others have called Falkner “a novelist of impressive talent who avoided the nostalgia prevalent among the romantic writers of the New South.” The White Rose of Memphis, with sales of more than 165,000 books, became Falkner’s best-known novel and gets credit for earning him sufficient money to finance his railroad. The work, a murder mystery set on board a steamboat of the same name, was reissued in 1953 with an introduction by Robert Cantwell and has since earned many reprints. Amazon describes the current publisher’s belief that “this work is culturally important, and despite the imperfections, [we] have elected to bring it back into print as part of our continuing commitment to the preservation of printed works worldwide. We appreciate your understanding of the imperfections in the preservation process, and hope you enjoy this valuable book.”

Biographers credit Falkner with being a “prototypical ambitious, self-made businessman in a frontier still marked by violence.” He put his town on the map when he built the Ripley Railroad Company, with trains running from the town incorporated in 1837 to Middleton, Tennessee. Four years later, the name changed to Ship Island, Ripley & Kentucky Railroad, and more changes followed over time. Modern-day tracks in Ripley follow Falkner’s original lines.

A novelist who also wrote poems, plays, and a travelogue, Falkner himself experienced the topic of his first work: murder. Having become known as the Old Colonel, he attracted the ire of Robert Hindman, who accused Falkner of slander and shot twice at him but missed his target. They scuffled before Falkner managed to get his pocketknife and stab Hindman to death. Indicted and tried for murder, Falkner was acquitted on self-defense, but a friend of Hindman subsequently challenged him to a duel. Falkner accepted, won, and once again stood trial for murder. Again, he gained acquittal on self-defense.

Putting those controversies behind him, Old Colonel entered politics and won a seat in the Mississippi Legislature. He never served, though, because on election night, former business associate R. J. Thurman shot and killed him. Thurman, also wealthy and a prominent citizen, was acquitted for the crime.

After funeral services at Ripley Presbyterian Church, the family buried Falkner in the Ripley Cemetery, where a full-size marble statue he himself imagined dominates. Chancey Rogers of Tennessee modeled the statue to convey Falkner’s stature in the community.

Falkner’s legacy lived on and continues through his great grandson William Faulkner (September 25, 1897—July 6, 1962). Faulkner scholars have credited the elder Falkner as “the model for the character of Colonel John Sartoris, who appeared in the novels Sartoris (1929; reissued in an expanded edition as Flags in the Dust, 1973) and The Unvanquished (1938), as well as a number of short stories. Thus, Colonel Falkner is the inspiration for an integral part of the history of Faulkner’s fictional Yoknapatawpha County. Faulkner’s short story “Knight’s Gambit” (in the 1949 collection Knight’s Gambit) has been viewed as including a commentary on Falkner’s The White Rose of Memphis (1881).

In Requiem for a Nun, Faulkner described his fictionalized version of his great-grandfather “with his virgin blade and his pristine colonel’s braid on the courthouse balcony, bareheaded too, while the Baptist minister prayed and the Richmond mustering officer swore the regiment in.”

William Faulkner drew heavily on the stories he had grown up with. Stories about his great-grandfather feature his war service, his post-war business dealings, and his death.