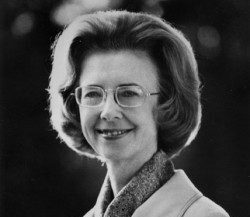

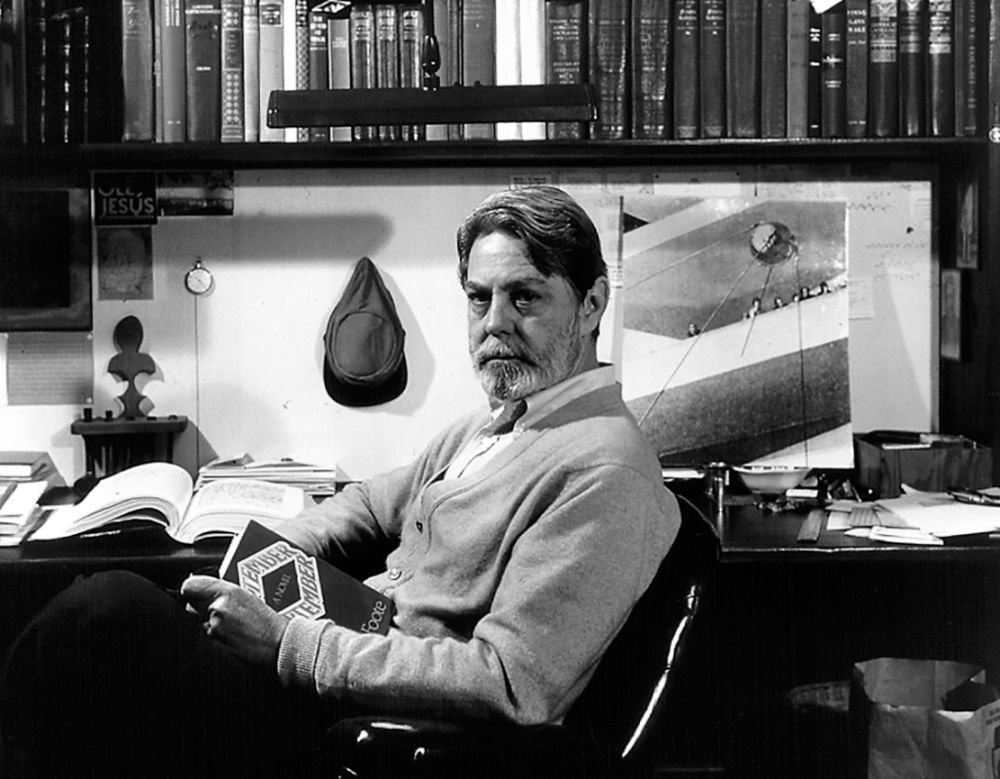

Shelby Foote (CQ) in a photograph published in Mid South Magazine March 19, 1978. Novelist and historian Foote, whose Southern storyteller's touch inspired millions to reads his multivolume work on the Civil War, died Monday night. June 27, 2005. He was 88. (By Charles Nicholas / The Commercial Appeal )

Shelby Foote became known as an “historian,” but he always thought of himself as a novelist.

“Writing is very hard work,” declared the Mississippi author invited to write a short history—two hundred thousand words—about the Civil War and who over two decades wrote three volumes and three thousand pages finally titled The Civil War: A Narrative.

The volumes—published in 1958, 1963, and 1974—captured the nation’s attention in 1990 through Ken Burns’ PBS documentary, The Civil War. Before that, Shelby Foote had not been known among America’s foremost fiction writers. PBS introduced the production that acquainted forty million viewers to a war Foote believed to have been “central to all our lives.” The “comprehensive and definitive history of the American Civil War” featured Foote in eighty-nine appearances and received forty major film and television awards, including two Emmys and two Grammys.

Shelby Foote became known as an “historian,” but he always thought of himself as a novelist. Notably, he wrote at home, without distraction, by hand with a nib pen, and later transcribed his words to a typewritten copy. For thirty-five years, his editor was Robert Loomis, referenced as an old-school editor of big-time books. The author said his editor encouraged but did not “mess with the text” because he himself had perfected the prose through his deliberate, slow-paced process of writing, setting it aside for a while, and then reviewing before submitting. Likely, he said, only his friend Faulkner had that similar understanding with his editor(s), who might mark a manuscript a few times before he would scrawl, “Goddammit; leave it alone!”

A veteran of World War II—first in the Mississippi National Guard and then as a Marine—he returned to his native Greenville where he wrote radio copy and reported for the Delta Democrat Times. He also wrote fiction. When the Saturday Evening Post published his “Flood Burial” in 1946 and paid him $750, Foote quit his job and took to writing full time.

Used paperback copies of his first novel, Tournament, originally published in 1949 and re-released in 1987 sell for more than two hundred dollars.

Other novels followed: Follow Me Down (1950), Love in a Dry Season (1951) and Shiloh (1952). Telling the story of the bloodiest battle in America’s history from first person perspective, Foote introduced seven different characters and quickly sold six thousand copies. But both his novels and his epic historical account of the Civil War draw mixed reviews.

Foote himself was mixed. His heritage in the Mississippi Delta drew from a paternal great-grandfather who was a Confederate veteran, a lawyer, a planter, and a state politician who gambled away the plantation and most of the family’s other assets. His maternal grandmother was a Jewish immigrant from Vienna. Foote grew up under the influence of both the Episcopal Church and the Jewish Synagogue and became what he himself declared a “yellow-dog Democrat” and Civil Rights advocate. Orphaned to a single mother when only five years old, Foote finished high school in Greenville where he became lifelong friend and literary ally with Walker Percy, nephew of the attorney, poet, and novelist William Alexander Percy.

Roman, Athenian, English, and French historians Tacitus, Thucydides, Gibbon, and Proust, respectively, also influenced Foote’s writing. Though he all-but-demanded admission to the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill so that he could join his Percy friends, Foote preferred free-range learning to rigorous study, often skipping class to spend time in the library. After only about two years, he returned to Greenville and volunteered to join the military and, after the war ended, worked a short while with the Associated Press in New York City.

Foote based his storytelling on his own experiences and observations, especially those from his perspective as a boy from the Mississippi Delta. When he moved to Memphis, Tennessee in 1952, he “did not leave home” because Memphis is “the capital of the Mississippi Delta.” The themes and happenings in that place informed his novels and formed the foundation for his writing history—not as an academically and classically educated historian, but as an observer of his place. For writing The Civil War: A Narrative, he read some 350 books and visited battlegrounds, and he employed the novel’s components of beginning, middle, and end with a definite arc to guide his telling of history.

Visiting Civil War sites from Memphis to New York on his fairly frequent road trips enabled his “feel” for the military actions. He went to those places at the same time of year the battles had been fought; he said one must “feel it to understand the weather, the soil, the feeling” the soldiers had as they strove to win for their side, and he particularly connected with the South. Given a call even late in his life to have joined either side, he “would have been on the South’s side. I’m from Mississippi. I would have fought with my people—not for slavery but for freedom, for the freedom to secede.”

Foote considered both Abraham Lincoln and Nathan Bedford Forrest “geniuses of the war,” and he fiercely condemned slavery:

The institution of slavery is a stain on this nation’s soul that will never be cleansed. It is just as wrong as wrong can be, a huge sin, and it is on our soul. There’s a second sin that’s almost as great and that’s emancipation. There should have been a huge program for schools. There should have been all kinds of employment provided for them. Not modern welfare, you can’t expect that in the middle of the nineteenth century, but there should have been some earnest effort to prepare these people for citizenship. They were not prepared, and operated under horrible disadvantages once the army was withdrawn, and some of the consequences are very much with us today.

Both praised and criticized for his work—beautifully crafted prose but without footnotes or much mention of social, economic, and racial themes—Foote said the Civil War happened when the country “was in its adolescence—had not formulated itself as an adult nation” and is the “outstanding event in American history so far as making us what we are.”

The War happened, he said, “because we failed to do what we really had a genius for, which is compromise. Americans like to think of themselves as uncompromising; our true genius is for compromise. Our whole government’s founded on it, and it failed.”

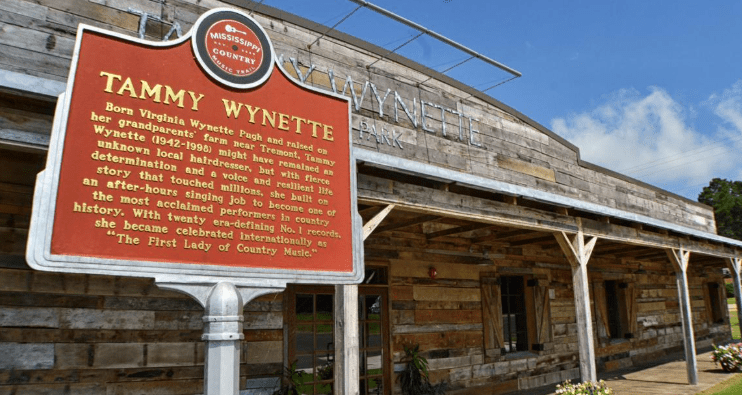

The Mississippi Writers Trail paid tribute to Foote in 2019 with erection of his cast aluminum marker in Greenville. Acknowledging that his romanticizing the Lost Cause earned him criticism, the marker notes that he died June 27, 2005, in Memphis.