There is a gator in the woods, and in theory, if not zoological fact, the southern conservative who has lurked just beneath the surface of national politics for so long should find a natural habitat here in the northern state that reminds the rest of the country to “live free or die.”

Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis has traveled to New Hampshire on the eve of summer to test that theory. He probably won’t know the answer until next year and by then, there will be snow. The gator, his unofficial campaign mascot, could just as easily freeze to death. Others from Florida have.

The metaphor only goes so far, but clearly DeSantis sees in libertarian-leaning New Hampshire, host of the first 2024 presidential primaries, an opportunity to burnish his anti-establishment credentials and begin the long process of clawing the nomination away from Donald Trump.

DeSantis attacked “entrenched elites” in Congress. He asked, rhetorically, in rural parts of the state why “five of the seven wealthiest counties in this country” border Washington, D.C. He warned voters during four different stops across the state that if they just looked at very recent history, “the last four or five years in this country,” they could “see firsthand how fragile freedom really is.” More than anything, DeSantis promised to fight. And the voters who crowded into at-capacity lodges and gymnasiums seemed to love it.

“What undergirds the flavor of New Hampshire and Florida conservatism is a very libertarian culture,” Jason Osborne, the Republican majority leader of the state House of Representatives, told RealClearPolitics. They may differ on particulars, he said, but “at the end of the day, it’s all about getting government out of people’s lives, letting people be free to do what they want.”

Osborne backed Trump during the last general election, support that has since run its course. The moment he broke with the former president? “For me, it was ‘two weeks to flatten the curve.’”

A once-in-a-century pandemic catapulted DeSantis into the national spotlight, with his opposition to the COVID-19 restrictions elevating him to folk-hero status on the populist right nearly overnight. Three years later, he has no appetite for abandoning his most reliable foil, the recently retired Dr. Anthony Fauci, who served as architect of the lockdowns that conservatives loathe. On Thursday, the governor again leaned on his most reliable applause line, reminding New Hampshire voters that, in Florida, “we chose freedom over Fauci-ism, and we were right.”

With the pandemic receding in the rearview mirror, DeSantis is attempting to make his origin story into a springboard. The broader threat, he says, is an unaccountable bureaucracy in Washington that had “imposed its will on us for far too long.” For a change, he vowed, “It’s about time we impose our will on it.”

In DeSantis’ telling, what Washington imposed on the country when the coronavirus hit these shores is much more than an arcane question of administrative law but as an existential threat to “the future of constitutional government.” Cameron Cole, a rising junior studying at Western New England University, who traveled to Rochester to see the candidate, agreed.

Pandemic restrictions wrecked his final year of high school and drew his attention to DeSantis. In turn, the belief that he “absolutely will not” enjoy as good or better a life than his parents earned the governor his vote. “The government has expanded so much at the federal and state level, and in blue states, that it’s almost beyond repair,” Cole said to explain his pessimism. “I thought Trump could have taken care of it a lot more than he did. It’s the reason I support DeSantis.”

DeSantis has pitched himself as a cunning and disciplined executive capable of doing what Trump could not, namely tackling the so-called deep state that the governor increasingly condemns as a “leviathan” pushing its own progressive agenda despite the will of the electorate. He warns this will take time. Eight years, perhaps. For Trump, who can only serve one term if re-elected, that would be a constitutionally prohibitive timeline.

Across the continent in Iowa, Trump begged to differ, promising that the job “will take me six months.” DeSantis fired back during a stop in Salem, telling voters that “anyone who says they can slay the deep state in six months should be asked, ‘Why didn’t you do that when you had four years to try?’”

Only a two-term president could finish that job, DeSantis insisted, because otherwise, “the bureaucrats will wait you out if you’re a lame duck president.”

That particular exchange was different, and not just because the back-and-forth was substantive. It also reflects an emerging willingness to go on offense. DeSantis aides have described their strategy for dealing with the former president as one where the governor makes an affirmative case for himself while lying in wait for Trump to slip up during an attack. During the rebuttal – that’s when DeSantis would clamp down. Until now, the DeSantis critique of Trump had been implicit.

His campaign has blasted Trump’s explanation for not firing Fauci for fear he’d take “heat” in the press. The governor, meanwhile, says that a true leader wouldn’t “put his own short-term political calculations ahead of the greater good.”

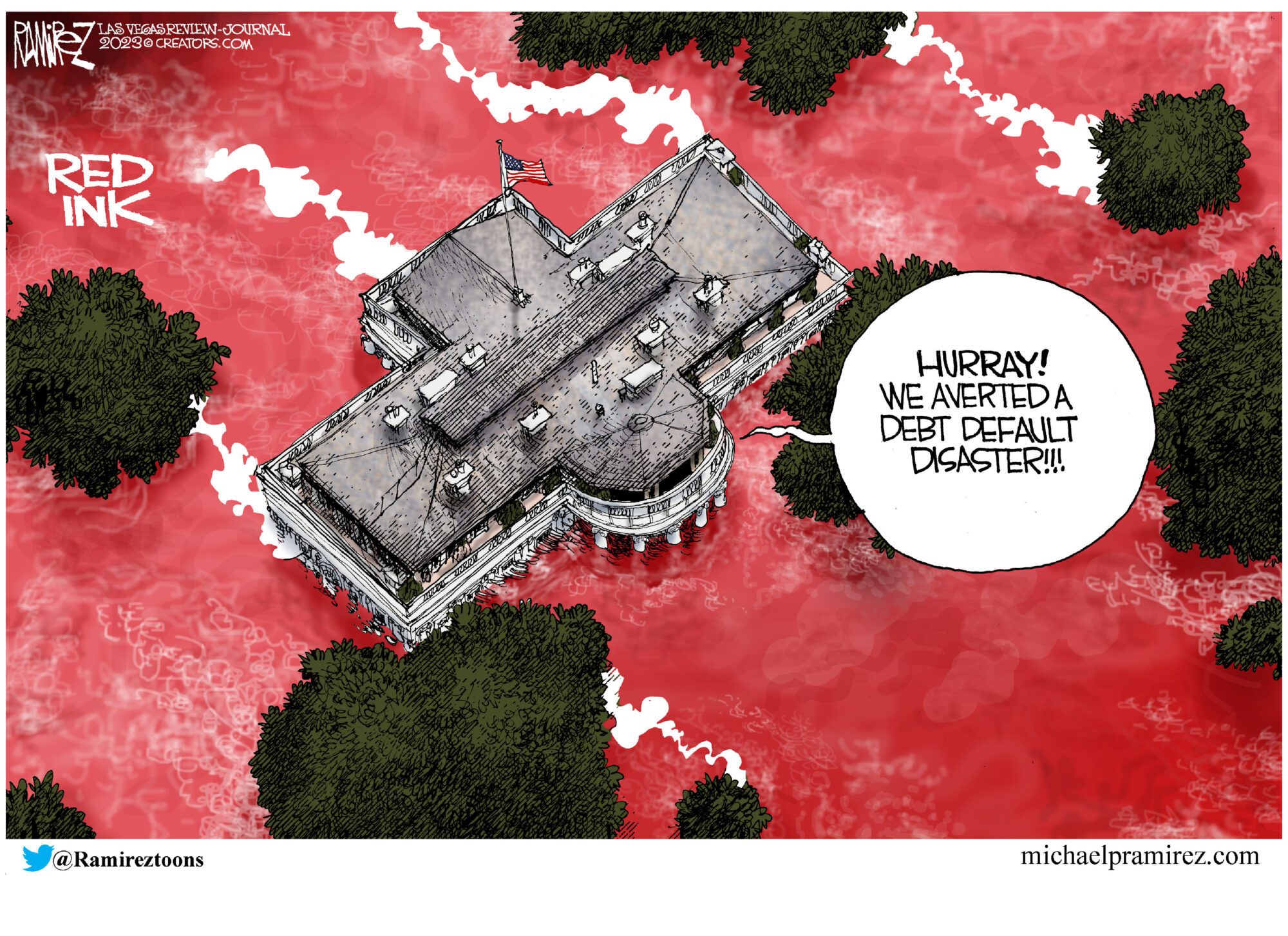

And as the former president stays mostly quiet on the much-maligned debt ceiling agreement that House Speaker Kevin McCarthy made with the White House, DeSantis seemed to lay ultimate blame at Trump’s feet, saying the GOP would have had a majority in the Senate had the party not “flubbed so many races over the last four, six years.”

Renewing the argument that he’s the only Republican running who can beat Biden, DeSantis cautioned voters, “We’re not getting a mulligan with this 2024 election. We’ve got to get it right.”

That is easier said than done. DeSantis starts the primary season in a deep hole, trailing Trump in the RealClearPolitics Average by more than 30 points nationally and by 18 points in New Hampshire specifically. As the clear second choice to Trump, the rest of the Republican field hopes to poach his position. Looking in from the outside, Democrats are already meddling.

Liberals argue the governor is “worse than Trump,” while the White House regularly rebuffs Florida as an example of how not to govern.

Lisa Teeman sees all of this and describes the contest as a sort of Florida Man vs. The World slug fight. A recent retiree who moved from the Sunshine State to New Hampshire, she believes the criticism of DeSantis from the left stems from the fact that “Trump cannot beat Biden” and “that’s why Democrats want Trump to win.” After hearing from DeSantis in Laconia, she believes “he may be able to gain some Democratic votes while Trump might lose Republicans.”

DeSantis enjoys something of a built-in federalist critique over much of his competition. As a state executive, he invites comparison with Florida, regularly running down a checklist of recent accomplishments and promising that what worked in Tallahassee can quickly be exported to the nation as a whole. This should appeal to Republicans in New Hampshire, particularly when it comes to economic issues, said state Rep. Jess Edwards, who explained, “We are really compatible from that perspective.”

Another area where the governor may soon enjoy an advantage, particularly among social conservatives: the ongoing culture war. DeSantis promises to finish it. Trump now seems to imply that voters don’t even understand it.

The former president, who has relished the culture wars and once said that “everything woke turns to shit,” added to the confusion when he suddenly abandoned the term. “Half the people can’t even define it,” Trump told an Iowa voter when answering a question about biological men competing in women’s sports, and “don’t know what it is.”

Fighting “wokeness,” a term the right uses as a catch-all for political correctness, is practically DeSantis’ trademark. He often brags that “Florida is where woke goes to die” and renewed his call in New Hampshire to leave “woke ideology in the dustbin of history” by weeding out government-mandated diversity policies from public education and the military.

Seeking to capitalize on Trump’s confusing verbal retreat, the DeSantis campaign blasted out an endorsement from former University of Kentucky swimmer Riley Gaines early Friday morning. The collegiate swimmer, who competed and lost against transgender swimmer Lia Thomas in the 2022 NCAA swimming championship, said the governor had earned her support. “He’s really taken on this political establishment, the woke corporations, the media,” she said. “And he’s won.”

Allies of the governor are confident that a primary race about principle and policy would naturally favor DeSantis in the long run. This would require something seldom attempted and never successfully achieved: an ideological challenge to Trump from the right that forces the former president to defend his record on its merits rather than fending off opponents through name-calling.

“I’m just hoping there’s enough voters out there that are looking for that kind of substance over showmanship,” Osborne told RCP as a large crowd of several hundred filtered into the gymnasium of Manchester Community College. The New Hampshire Republican predicted optimistically that Trump’s “floor of support” would also prove to “be his ceiling.”

“He’s not going to be able to rise above that because people are just tired of it,” Osborne continued, comparing Trump to an artist who had been “overplayed” and “hasn’t put out a new CD yet.”

But many of the MAGA faithful will always love the greatest hits. Outside the college before the event began, several dozen supporters waved Trump banners, flags, and signs in support of the newly challenged former president. They weren’t tempted by DeSantis, at least not now.

Longtime conservative activist Di Lothrop said the governor should “wait his turn.” Her husband, Charles, vowed to vote for Trump in the general election no matter what: “I’m ready to write in Donald Trump if he doesn’t get the nomination.”

That won’t be necessary, though, insisted Bruce Breton, a longtime Trump supporter, who said the 2024 primary would be a repeat of the 2016 contest as more challengers enter the race. “Trump mowed down 17 before,” he said. “Trump will mow down 17 again.”

DeSantis believes he can survive such an extinction, that this time a gator can thrive up north. Inside the gymnasium, now at capacity – and exactly where an earlier Florida governor, Jeb Bush, celebrated an underwhelming fourth-place finish seven years prior – he promised he could win the White House.

“If you nominate me, you can set your clock to January 20, 2025, at high noon, because on the west side of the U.S. Capitol, I will be taking the oath of office as the 47th president of the United States,” DeSantis proclaimed. “No excuses. I will get the job done.”

Then he walked off stage to sign autographs and take pictures with a swarming, adoring crowd.

This article was originally published by RealClearPolitics and made available via RealClearWire.