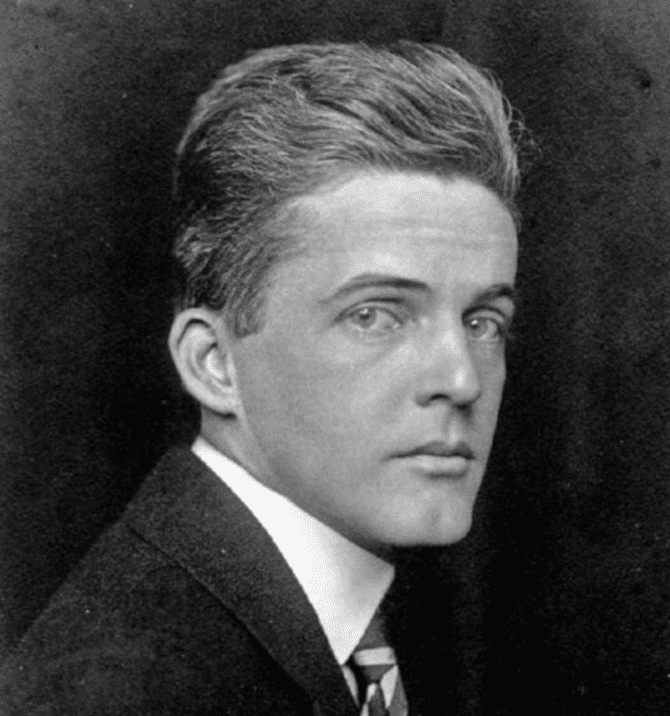

William Alexander Percy wrote his own story, published as Lanterns On The Levee: Recollections of a Planter’s Son just one year before he died in his hometown of Greenville in 1942.

Introducing his autobiography, he reflected that “reminisce arises … from the number of those who meant most to you in life … When they have gone, you are a little tired, you rest on your oars, you say to yourself … ‘It is better to remember, to be sure of the good that was, rather than of the evil that is, to watch the spread and pattern of the game that is past rather than engage feebly in the present play.’”

One biographer described the author as “a lawyer and man of letters, a poet, literary mentor, scion of a great family, friend of William Faulkner, and author of a bestselling memoir.” Percy was also the uncle and adoptive father of the more famous novelist Walker Percy, mentor to Shelby Foote, and persuader of Hodding Carter II to establish in Greenville a progressive newspaper now known as The Delta Democrat-Times.

Of Lanterns on the Levee, marketers have suggested the autobiography “is a volume to be treasured by those whose memories go fondly back to days of quieter, more contemplative living. For Percy was not in any sense a modernist; his love of tradition is as evident … in his prose. Here again is the same gentle quality of nostalgia which has made Lanterns on the Levee one of the most charming and authentic pictures of the Old South at its best.”

The book became a bestseller and remains in print and widely read eighty-two years later.

Out of Place

From his birth on Ascension Day 1885, Percy found fitting in difficult and knew himself to be sickly. Even his parents thought him odd. Educated largely at home and then the University of the South (Sewanee), he would travel to Europe and Egypt, study at Harvard University, and establish his place as his father’s law partner.

He preferred poetry, music, and art to hunting and fishing. He chose Harvard instead of his father’s Virginia to study the law: ”I wanted to be near Boston with its music and theaters, which I would miss the rest of my life in my future Southern home, and I wanted to meet the damyankees.”

From 1915 through 1930, the “unabashed elitist” with Yale University Press published four volumes: Sappho in Levkas, and Other Poems; In April Once, and Other Poems; Enzio’s Kingdom, and Other Poems; and Selected Poems. From 1925 to 1932, he edited the Yale Younger Poets series, the first of its kind in the country. Historians write that while at Sewanee, Percy “lost his faith in Christianity,” though not in God, and “developed the beginnings of a historical and philosophical explanation of same-sex desire that made sense to him.”

Published after Percy’s death are Silence of Stars, a book of poetry from the years before 1915 to sometime after 1920, and The Collected Poems of William Alexander Percy. He also wrote the text of “They Cast Their Nets in Galilee,” included in the Episcopal Hymnal (1982). Many of his writings reflect “extended meditation on love, death, and loss.”

Upon returning to Greenville, in what he described as “sheer lonesomeness and confusion of soul,” Will Percy took levee walks and wrote poetry: “What I wrote seemed to me more essentially myself than anything I did or said.”

Foray into Politics

Percy credited himself primarily as a writer, but political activities with his father, wartime successes, and leadership during The Great Flood of 1927 also are a unique part of his story.

“With no endearing vices,” Percy knew he did not quite measure up to his father, a prosperous planter and successful lawyer who enjoyed drinking, gambling, and being an elite aristocrat. In his father’s shadow, Percy never married, lived in the family mansion with his parents most of their lives, and with little enthusiasm practiced law with his father.

Through those years he recounted, with little affection but boundless admiration for his stern, high-spirited father, Percy fervently helped campaign against senatorial candidate James K. Vardaman. In a vote of eighty-seven to eighty-two, legislators elected Leroy Percy over Vardaman to serve as U.S. Senator until 1912. Leroy was the last legislatively elected Mississippian to the Senate.

The new Senator had never aspired to political office, but he had deemed the opponent unfit to serve in that seat of responsibility and honor. In the following first popular election to fill the Senate seat, Vardaman won. From the acrimonious defeat, the younger Percy claimed strength from seeing “evil triumphant, valor and goodness in the dust.”

Service in World War I

Four years later while vacationing in Europe, Percy began to see evidence of Germany’s aim to dominate England and France. He responded to a call for volunteers to serve on the Commission for Relief in Belgium during 1916. When the United States entered World War I, he returned to Greenville and embraced the frenzy of wartime patriotism. Despite his small physical size and aristocracy, Percy “wanted to join the army, the infantry, at once.”

Finally landing in the pee-wees squad and later deployed to France, Percy filled various assignments until he finally landed for duty on the front. Letters home detailed the hell of trench warfare. “It was all unreal, like a slow-motion nightmare, and unreal incidents kept happening … To each man battle was horrible and innocent, despicable and divine, torture but so austere and exalted that it invested the lowliest rumpled, unshaven participant with a fierce dignity, an arrogant worth.”

Though he hated war and felt unfit by temperament and ability, he credited that common endeavor as “the only great thing you were ever part of … the only heroic thing we all did together … You can’t go back to the old petty things without purpose, direction, or unity.”

Fight Against the Ku Klux Klan

On the way back to Mississippi, he landed in New York, greeted by his parents, having achieved captaincy and the French Medal of Honor for feats of bravery. At home, he faced a different enemy, what he called “the South’s two major deficiencies—character and education,” particularly troublesome because he found his hometown increasingly the target of the Ku Klux Klan.

Efforts to establish a Klan branch in Greenville in 1922 triggered Leroy Percy to bitterly ridicule the organizer, and his son Will to write, “Our town was disintegrated by a bloodless, cruel warfare, more bitter and unforgiving than anything I encountered at the front.” Greenville escaped physical violence, however, because the local Klan “bent all of its efforts toward electing one if its members sheriff.”

Both father and son aligned with people determined to prevent the Klan’s candidate from being elected. They succeeded. After the declaration of victory, the winners swarmed to the Percy home, cheering, drinking, and creating “a party never to be forgotten.”

The Great Flood of 1927

Another enemy of the town could not be turned away via the ballot box or effectively stayed through human effort. In the spring of 1927, people who called Greenville home nervously watched the weather as a stalled weather system and heavy rains flooded many Midwestern towns along the upper Mississippi River. The system also began to affect the Yazoo-Mississippi Delta.

Only a man-made levee, an earthen dam, lay between the Mississippi and Greenville. Steady rainfall filled streams, bayous, creeks, and ditches in the Delta and saturated the farmland. Levees broke in other states while two levees north of Greenville especially worried residents; a break at either would allow water into the Delta town with the county’s largest population of about 15,000 people.

As a youngster surveying a two-to three-feet overflow with his father, Will Percy recalled “a very jolly affair.” But by 1927 and as a grown man accustomed to helping guard the levee, he knew the disaster a torrential flood the size of Rhode Island would create for the entire Mississippi Delta and downstream to New Orleans. When sirens sounded to alert citizens the flood had arrived, the Percy family drug furniture and other possessions to the upstairs area. From the second-floor balcony, they somberly watched and waited as the water arrived and covered their property.

Having been appointed chairman of the Flood Relief Committee and the local Red Cross, Will Percy found himself “charged with the rescuing, housing, and feeding of sixty thousand human beings and thirty thousand head of stock. To assist me in the task I had a fine committee and Father’s blessing, but no money, no boats, no tents, no food.”

Lanterns on the Levee details the flood along with all its innumerable problems, successes, and failures. Thousands of both White and Black people suffered through the disaster with no way out; tensions escalated; tempers flared, and the flood waters stood. Despite his effort to be beneficent, Percy lived the nightmare he described as, “thirty-six hours coming and four months going.” Nobody saw dry land for four months.

By the last week of August, the Red Cross had mostly returned to normal. “I was exhausted, and I felt I had the right to resign as chairman.” Persuading his friend and future law partner to take his place, Percy sailed the next day for Japan, eventually returning to “find that the relief work had proceeded distressingly well without me.”

The End

Percy’s father, Leroy, died in 1930. After his parents’ deaths, he never again wrote poetry. He inherited the law practice and Trail Lake plantation, 3,343 acres farmed by 149 sharecropper families. He also adopted and devoted large amounts of time to his nephews Walker, LeRoy, and Phinizy Percy, whose father had committed suicide and whose mother died in a car wreck. Walker would go on to become a world famous novelist.

In addition to overseeing the Trail Lake and tending to his nephews, Will Percy devoted much of his time to completing Lanterns on the Levee. The book was published in 1941, just one year before his death at the age of 57.

Many memories flooded Percy as he increasingly visited his own at the cemetery, prompting this final analysis: “I count the failures—at law undistinguished, at teaching unprepared, at soldiering average, at citizenship unimportant, at love second-best, at poetry forgotten before remembered—and I acknowledge the deficit. I am not proud, but I am not ashamed … I have never walked with God, but I had rather walk with Him through hell than with my heart’s elect through heaven. Of the good life … I am grateful.”