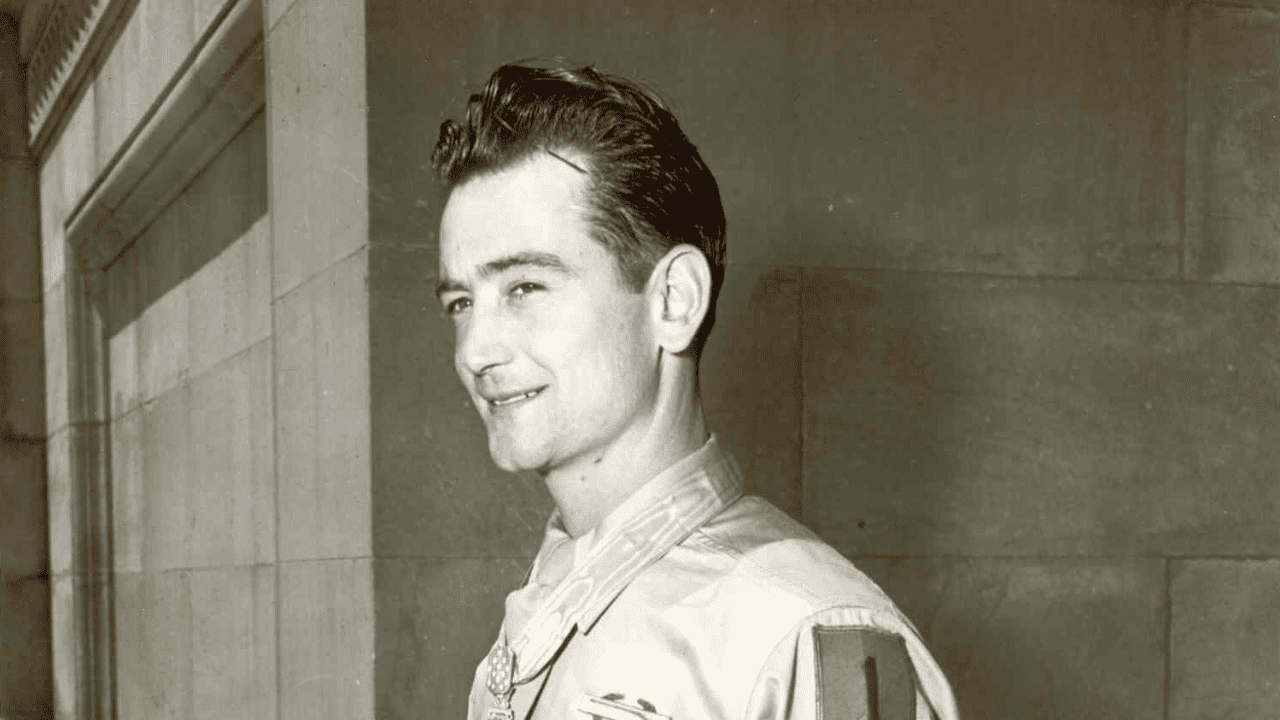

John Davis, former director of the Mississippi Department of Human Services confers with defense attorneys Merrida Coxwell, right, and Charles Mullins, left, in Jackson, Miss., on Thursday, Sept. 22, 2022. Davis pleaded guilty to new federal charges in a conspiracy to misspend tens of millions of dollars that were intended to help needy families in one of the poorest states in the U.S. — part of the largest public corruption case in the state's history.(AP Photo/Rogelio V. Solis)

Determining who goes to jail is a question for prosecutors, courts, and juries—based on evidence. It will not be decided by reporters on the back of cleverly constructed innuendo.

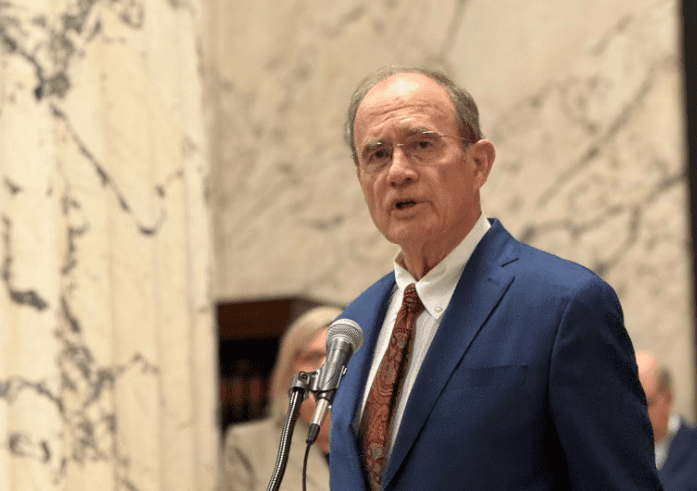

On June 21, 2019, Gov. Phil Bryant was alerted to possible irregular spending at the Mississippi Department of Human Services (MDHS) by then-Executive Director John Davis.

Bryant informed State Auditor Shad White’s office that day, according to White. Bryant’s tip triggered an investigation by the Auditor’s office that would uncover a sprawling conspiracy to embezzle Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) welfare money intended to aid Mississippi’s poor.

As the investigation got under way, Bryant asked for the resignation of Davis and brought in a former FBI agent, Chris Freeze, to help clean up MDHS.

In the wake of the investigation, both state and federal criminal proceedings ensued. Multiple charged parties have since pled guilty. A civil lawsuit was filed by MDHS to recoup some of the ill-spent money. Forty-six separate defendants have been named in that case.

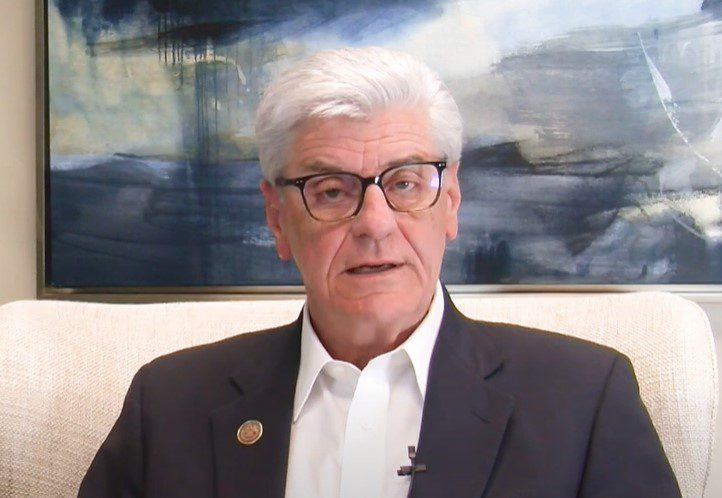

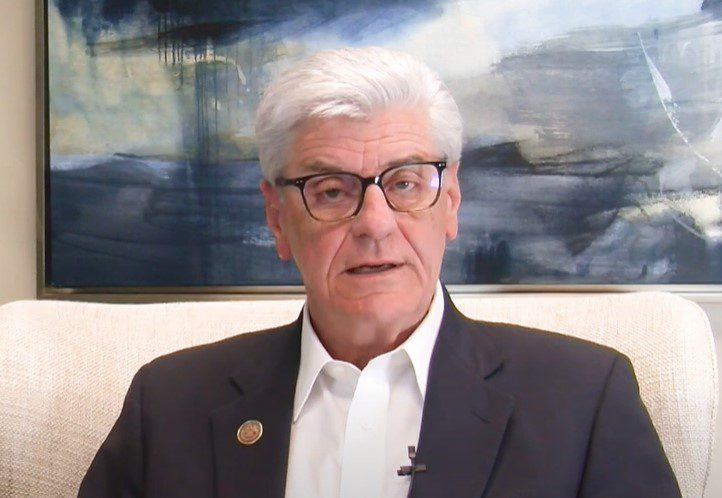

Phil Bryant is not among them. He has not been charged with any crime. He’s not been named in any lawsuit. But he has been tried in the court of public opinion for the better part of two years by zealous advocates in the media. This week he pushed back, releasing a video and text messages in his possession.

RELATED: Phil Bryant Release Video Responding to Media Coverage, Along with Related Communications

The TANF welfare scandal unquestionably marks a gross breach in public trust. What occurred was criminal and people will go to jail for it. Determining who goes to jail, however, is a question for prosecutors, courts, and juries—based on evidence. It will not be decided by reporters on the back of cleverly constructed innuendo. Guilt by innuendo is a reckless and dangerous precedent.

Media Framing of Narrative

Dozens of outlets across Mississippi, and many more nationally, have covered the TANF scandal. No outlet has made a more concerted effort to “own” the story, though, than Mississippi Today. Their coverage, particularly the investigative reporting of Anna Wolfe, has drawn both rave reviews and a fair amount of criticism. Wolfe’s reporting has also been used as source material by countless other publications and outlets, meaning it has largely framed public awareness of the scandal.

Mississippi Today’s CEO Mary Margaret White appeared as a panelist at a Knight Foundation conference in February of 2023. The Knight Foundation funds non-profit news organizations like Mississippi Today. These types of events are frequently “show and tell” opportunities. In a wide-ranging interview, White gave her outlet credit for both changing the Mississippi flag and breaking the story on the TANF welfare scandal.

The Mississippi flag was changed because of the courageous leadership of people like House Speaker Philip Gunn, who had advocated the change for years, bipartisan cooperation in the Legislature, and a strong coalition of business and faith groups. It was not changed because an outlet reported on it, but White’s commentary on the flag is reflective of how Mississippi Today sees itself—as an advocacy organization.

How White characterized the TANF welfare scandal speaks to how Mississippi Today has approached the story. “We’re the newsroom that broke the story about $77 million in welfare funds intended for the poorest people in the poorest state in the nation being embezzled by a former governor and his bureaucratic cronies,” she boasted from the stage.

Only no one has accused Phil Bryant of embezzlement, which has a very specific legal meaning. There is no public evidence that Phil Bryant embezzled, or that he benefitted personally in any way from the TANF fraud. He’s certainly not been charged with embezzlement.

But support for the claim aside, White’s perspective–her preemptive imputation of guilt– permeates her newsroom’s coverage. It’s simply sexier to contort the public record and paint Bryant as a criminal mastermind than to withhold judgment until the legal process is complete. Bryant buys clicks. Focusing on him also conforms to a pervasive anti-Republican sentiment in the midst of an election cycle.

The Heart of the Scandal

But there is a reason audits performed, criminal prosecutions brought, and lawsuits filed have instead focused on former MDHS Executive Director John Davis, Mississippi Community Education Center head Nancy New, and Family Resource Center head Christi Webb. They are at the heart of the scheme—uniquely positioned to pull it off and with clear evidence they derived benefit from it.

If someone wanted to understand the scheme, they could start by reviewing relevant portions of the State Auditor’s Single Audit for the Fiscal Year Ending June 30, 2019 (bulk of MDHS coverage appears between pages 101-276), an independent third-party audit performed by CliffordLarsenAllen on behalf of MDHS, an expanded email audit performed by CliffordLarsenAllen, and MDHS’s amended complaint, which does a good job of detailing the people, events, legal duties, and allegations in the case.

Both MCEC and FRC were already subgrantees for administering MDHS’s TANF State Plan prior to Davis assuming his post in January of 2016. However, after becoming Executive Director, Davis dramatically ramped up the TANF funding pouring into both organizations.

In exchange for the increased funding, New and Webb spent lavishly on Davis, his family, and his favored friends. There is a massive web of people who benefited from this scheme by receiving unallowed TANF expenditures. Davis directed both MCEC and FRC to pay family members for phony leases on non-existent buildings, and to pay family and friends millions of dollars in consulting contracts for services they were unqualified to offer, and in most cases, did not perform.

Millions, for instance, were spent on a family of wrestlers, the DiBiases, to provide services they had no special skills to provide. It appears Davis just had some peculiar fascination with them.

There is evidence that New and her family also benefitted personally from the scheme, treating the TANF funds flowing through MCEC like a piggy bank to support family-owned ventures.

Davis, New, and Webb have all pled guilty to various offenses and are facing significant time in prison.

Is there hard evidence against Phil Bryant?

There is zero public forensic evidence that Phil Bryant knew anything about the scheme between Davis, New, and Webb prior to June 21, 2019, when he was alerted by Jacob Black, a then-MDHS Deputy Director who has since been added to MDHS’s lawsuit as a defendant. It’s not even clear what Bryant was alerted to that day. Emails uncovered in an audit from the same time period suggest the tip could have been limited in scope to unauthorized luxury travel by John Davis and Ted DiBiase, Jr. to Washington, D.C.

While others walked away with millions, there is also zero public evidence that Phil Bryant reaped any personal benefit from the scheme.

Instead, the information used against Bryant in the media comes from text messages, primarily with Brett Favre, about two projects that Favre was pushing—the construction of a volleyball facility at Southern Miss and a concussion drug named Prevacus, for which Favre was an early investor.

Bryant was encouraging of both projects in his texts with Favre and both projects eventually received TANF funding. If the analysis stops there, the optics are bad. But a closer look provides important context.

In none of Bryant’s texts does he suggest that these projects should be funded with TANF dollars. What you actually see in both cases is a governor offering to use his connections to privately fundraise for both projects. Take for example this exchange on April 20, 2017:

- Brett Favre: “Deanna and I are building a volleyball facility on campus and I need your influence somehow to get donations and or scholarships. Obviously Southern has no money so I’m hustling to get it raised.”

- Phil Bryant: “Of course I am in on the Volleyball facility…We will have that thing built before you know it. One thing I know how to do is raise money.”

This theme around helping to make fundraising connections persists throughout Bryant’s released texts. Bryant helped find a contractor to build lockers for the facility and even sent a personal donation.

Bryant publicly and voluntarily released texts this week. Those texts, and other communications, can be viewed here.

Two Paths for Funding

What has not been seriously considered in media coverage of these two projects is the potential of two sets of conversations being pushed by Brett Favre—one set with Bryant that focused on fundraising, and another set with Davis and New that focused on public funding. That dichotomy is actually supported by the available communications and goes a long way to explaining Bryant’s state of mind in his conversations with Favre.

The impression created in coverage to date is that Bryant was the nexus between Favre, New and Davis. But Favre, New, and Davis ran in the same circles as Southern Miss alumni. Favre and New sat on USM’s Athletic Foundation Board together. New had been approached by Jon Gilbert, then-Athletic Director at USM, about help in building the volleyball facility, and was ultimately introduced by Gilbert to Favre, for the purpose of helping.

A considerable body of meetings and communications between USM officials, Favre, MDHS personnel, and New to determine how to arrange payment for the facility took place. There is no evidence that Phil Bryant was a party to these discussions.

The structure to fund the stadium was ultimately devised by MDHS personnel—a sublease arrangement to get around a TANF prohibition on brick-and-mortar spending. This arrangement was ultimately signed off on by USM, Special Assistant Attorney General Stephanie Ganucheau, and the Institute for Higher Learning. Minutes from an IHL meeting on October 17, 2017 read:

This lease and subsequent sublease are being funded through the lease of athletic department facilities by the Mississippi Community Education Center (MCEC), a 501(c)(3) organization designed to provide schools, communities and families with educational services and training programs in South Mississippi. MCEC will use the subject facilities to support their programming efforts for South Mississippi. MCEC’s funding for the project is via a Block Grant from the Mississippi Department of Human Services. The funding from MCEC shall be prepaid rent to the Foundation in the amount of Five Million Dollars ($5,000,000).

Again, there is no public evidence that Phil Bryant was involved in devising the structure of the deal. He had no authority to approve the expenditure. Instead, it was approved in plain sight by the people who had the authority. It also bears noting that most governors are not in the weeds of the day-to-day operations of agencies, nor are they issue experts on all of the regulations that may apply to an individual agency. The scope of their work is simply too broad and they must rely on agency personnel.

A similar pattern to that of the volleyball facility emerges with respect to Prevacus, the concussion treatment. Favre and New having one set of conversations, and Favre and Bryant having another. Bryant’s offer of help in texts is to connect Favre to donors and people within the Trump White House who might be able to help with the FDA.

Caution with the Court of Public Opinion

It is possible that reporters know more than the prosecutors in this case, or the lawyers who have filed to recoup stolen funds. Possible, but not probable. It’s more probable that the people who understand the law and have a full grasp of the evidence have not gone after Bryant, nearly four years into the investigation, for a reason.

In examining anything as complex as the TANF welfare scandal, healthy skepticism is warranted. The sheer volume of players and schemes involved will one day fill books. Even for honest reporters, distilling the scandal down into bite-sized pieces is difficult and can be misleading.

The risk is amplified when you consider that the information circulating could be incomplete, or worse, calculated to advance an agenda. Much of the information reported about the TANF investigation to date has been gleaned from audits, legal proceedings, and anonymous sources, then seasoned with opinion.

RELATED: Judge Enters Gag Order in MDHS Lawsuit Following Bryant Release of Texts

Because of the nature of an ongoing investigation and litigation, a complete body of evidence is elusive. Sources, both anonymous and public, often act out of self-interest in sharing information. An attorney for a person charged, for instance, might have motive in communicating with media to deflect blame from his or her client onto others. In furtherance of that motive, they might selectively share or frame information.

Likewise, a government official who communicates covertly with reporters might be doing so to escape personal scrutiny, remove political competitors, or advance their own careers. Reporters must weigh those factors, and the nature of their relationships with sources, in checking bias and deciding what is credible to report.

In court cases, claims must be backed by evidence. Evidence is filtered through rules to ensure it is relevant and reliable. People charged with crimes or named in civil lawsuits are given a fair chance to challenge evidence.

Unfortunately, the rules of evidence and the right to challenge that evidence through the crucible of trial do not apply in the court of public opinion. A reporter who wants to drive a narrative can selectively omit evidence, editorialize, and exclude voices that would offer challenge.

Guilt by innuendo is a dangerous thing. Caution in accepting it.