A new report by the Center for Healthcare Quality & Payment Reform shows a dramatic decline in the number of at-risk rural hospitals in Mississippi over a six month span, but does not tell the whole story.

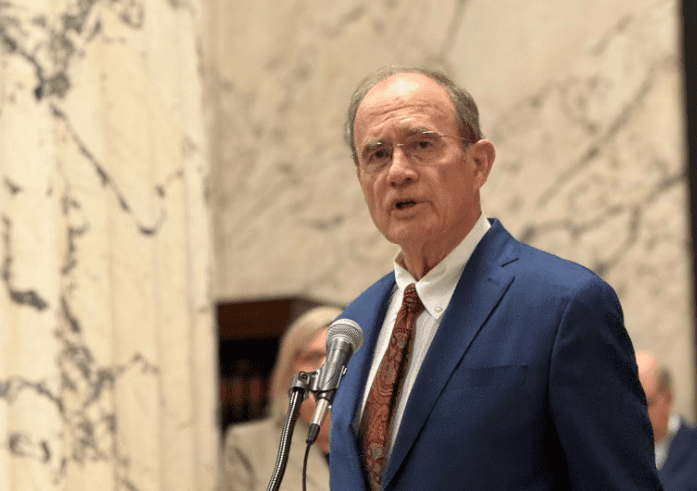

In October of 2022, the Center for Healthcare Quality and Payment Reform (CHQPR) published a report indicating 38 rural hospitals in Mississippi were at risk of closure. The data was parroted by the Becker Hospital Review, and eventually, offered in testimony to the Mississippi Senate by State Health Officer Dr. Daniel Edney.

“38 rural hospitals” was repeated over and over and over again by media across the state and nationally, often in conjunction with not-so-subtle advocacy in favor of Medicaid expansion.

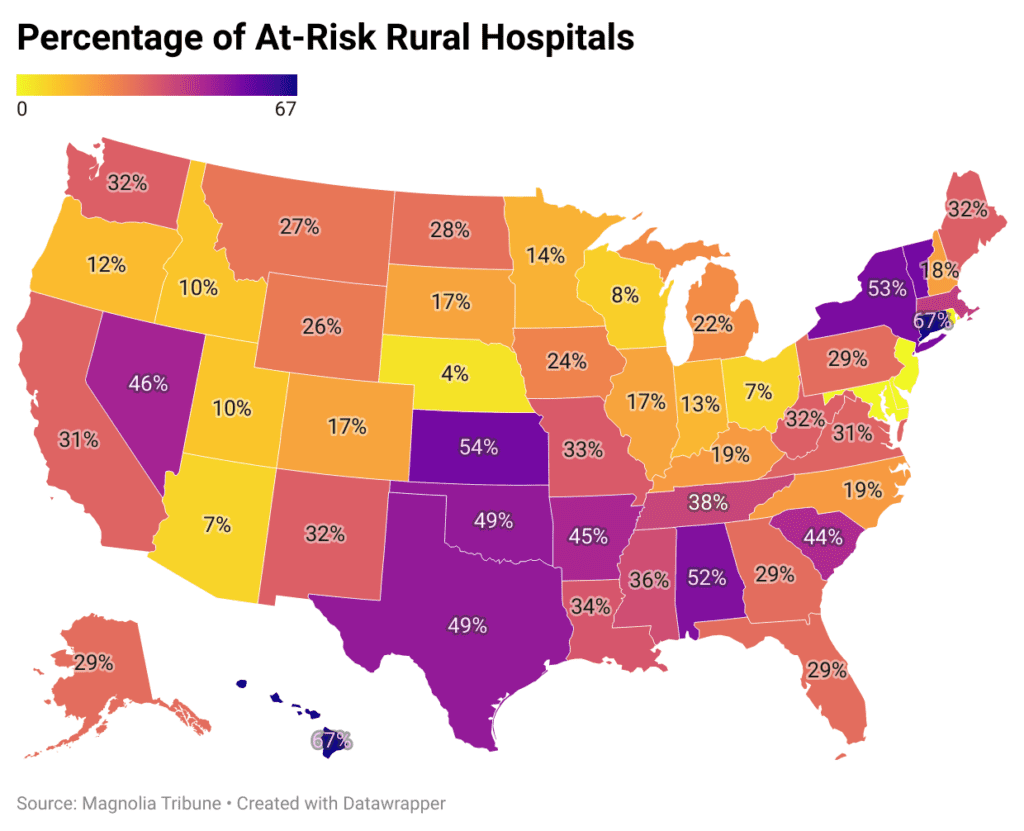

But over the last two quarters, new version of CHQPR’s report has shown a steep decline in the number of at-risk rural hospitals. The updated report now says 27 rural hospitals are in jeopardy in Mississippi, a 29 percent drop from the number reported in October of 2022.

The new report puts Mississippi in 37th place for the percentage of at-risk rural hospitals. States in worse shape—with higher percentages of rural hospitals in danger—include Medicaid expansion states Arkansas, Connecticut, Hawaii, Massachusetts, Nevada, New York, Oklahoma, and Vermont.

It bears mentioning that the CHQPR report indicated that data from the last full year available is used to make these determination, but does not indicate what the last full year available is for each state. In other words, the data could be stale. It also bears mentioning that CHQPR has a very specific set of reforms it advocates for, and that to my knowledge, there is no assessment of how accurate the report has been in predicting closures.

It should be noted that the Mississippi Legislature recently passed $103 million in grants to help rural hospitals.

RELATED: Legislature Passes $103 Million in Grants to Help Mississippi Hospitals

Broader Context Important

Parroting the CHQPR report’s number might serve to alarm. The Democratic Governor’s Association, citing Mississippi Today’s reporting on the CHQPR data, put out a press release in favor of gubernatorial challenger Brandon Presley and Medicaid expansion.

Previous versions of the CHQPR identified Medicaid expansion as a “commonly proposed solution” that “won’t precent most closures.” That section did not find its way into the updated report. The report does, however, contain a less explicit caveat about the efficacy of relying on Medicaid payments to solve rural hospitals’ problems:

Most “solutions” for rural hospitals have focused on increasing Medicare or Medicaid payments or expanding Medicaid eligibility due to a mistaken belief that most rural patients are insured by Medicare and Medicaid or are uninsured. In reality, about half of the services at the average rural hospital are delivered to patients with private insurance (both employer sponsored insurance and Medicare Advantage plans). In most cases, the amounts these private plans pay, not Medicare or Medicaid payments, determine whether a rural hospital will have to close.

That eight of the thirteen states with higher percentages of rural hospitals at risk are expansion states certainly suggests that there’s more to the story. The number of at-risk hospitals carries little meaning without additional context. Specifically, it bears considering whether a state’s hospital infrastructure might be overbuilt and reasons why rural hospitals are struggling in the first place.

Mississippi Has A Lot of Rural Hospitals & A Lot of Hospital Beds

Only six states have more rural hospitals than Mississippi. Only two states, North Dakota and South Dakota, have more hospital beds per 1,000 citizens than Mississippi. A look at surrounding states shows a much smaller number of rural hospitals despite far larger populations, and far higher bed utilization rates.

| States | Population | Rural Hospitals | Beds Per 1,000 Citizens | Bed Utilization Rate |

| Alabama | 5.04 million | 52 | 3.05 | 74% |

| Arkansas | 3.03 million | 49 | 3.17 | 73% |

| Louisiana | 4.62 million | 53 | 3.24 | 69% |

| Mississippi | 2.95 million | 74 | 3.95 | 62% |

| Tennessee | 6.97 million | 52 | 2.72 | 74% |

Approximately thirty-eight percent (38%) of Mississippi’s hospital beds are unfilled. But even this is misleading. Many rural hospitals have far higher rates of vacancy.

The overarching picture is one of a tremendous supply of unused beds. Covering staff and overhead for a half-empty facility is a tough proposition irrespective of payment models.

Why Are Mississippi Hospitals Struggling?

There are two chief problems facing these facilities. First, rural communities are losing population. The trend is for people to move to more urban and suburban settings. In Mississippi, cities like Madison, Brandon, Southaven, Gulfport, Biloxi, Hattiesburg, and Oxford have experienced substantial population growth. Areas like the Mississippi Delta have seen dramatic declines.

LeFlore County, where Greenwood-LeFlore Hospital is located, has seen nearly fifteen percent (15%) of its population leave over the last decade.

The second pain point for rural hospitals comes from real changes in how health care is delivered. The era of medical treatment or surgeries followed by long hospital stays is largely over. Outpatient care is the new normal, meaning lower bed utilization rates.

Rise of Outpatient Care

While hospitals offer outpatient procedures, ambulatory surgical centers are rapidly gaining market share. The U.S. ambulatory surgical centers (ASC) market was $35 billion in 2020. Growth is projected, at a compound rate of 6.9 percent, to $59 billion in 2028. The projected growth rates are consistent with employment forecasts.

The Bureau of Labor Statistics predicts that the healthcare sector will generate approximately 3.4 million new jobs through 2028. More than half of these new jobs will be in ambulatory care services. Only 350,000 are projected to be in hospitals.

Cost is a primary driver for the shift to ambulatory care. A study performed by UnitedHealth Group found that outpatient procedures at ASCs were typically 59 percent less than outpatient procedures performed at hospitals. This meant a total cost savings of $4,559 per procedure and average savings to the patient of $684.

Private insurers are not the only ones moving toward ASC provided out-patient care. In 2020, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) proposed a payment increase for ASCs. The proposed increase aimed to create site neutrality between hospitals and ASCs. CMS has signaled a desire to remove many procedures from its in-patient only list. It has also actively added procedures that it will cover in ASC settings.

It is impossible to experience double-digit population loss, at the same time as system-wide upheaval in delivery of care, and not expect falling demand at rural hospitals. For hospitals that were built to serve larger populations, these factors place an understandable strain. But that strain has very little, if anything, to do with Medicaid expansion. Occupancy rates at hospitals reflect the changing dynamics.