Sid Salter

Columnist Sid Salter says Mississippi Rotarians remain in that fight in helping eradicate polio.

U.S. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, Olympian Wilma Rudolph, actors Donald Sutherland and Alan Alda, golf legend Jack Nicklaus, NFL Head Coach Bud Grant, New York City Ballet principal dancer Tanaquil Le Clercq, Washington Post editor Ben Bradlee, and Israeli American violin virtuoso Itzhak Perlman. What do these notable Americans all have in common?

They all contracted poliomyelitis before the development of vaccines but survived. The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) and the World Health Organization (WHO) estimate that over 12 million people have been touched by polio with over 300,000 polio survivors in the U.S.

But thanks to the Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI) – a public-private partnership led by national governments with six core partners including the CDC, WHO, the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the international vaccine alliance GAVI, and Rotary International – polio has been eradicated in 99.9 percent of the planet since this effort began in 1979 through vaccinations.

With 200-plus countries involved, GPEI has raised $17 billion and deployed over 20 million volunteers to accomplish the vaccination of over 2.5 billion global children. Polio is now endemic only in parts of Afghanistan and Pakistan with

Rotary International has been a force for good in Mississippi in communities large and small for decades. The mission of Rotary International? “We provide service to others, promote integrity, and advance world understanding, goodwill, and peace through our fellowship of business, professional, and community leaders.”

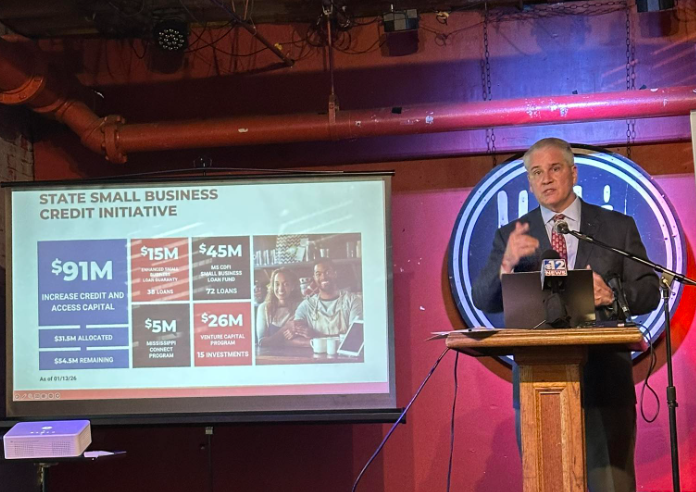

Rotarians celebrated their work in helping eradicate polio this week in Jackson. Rotarians have raised $2.1 billion in donations from members toward the effort, yet the fight continues.

As outlined in the international health journal Nature in August: “Fears that eradication was falling out of reach increased again in 2021, when wild poliovirus broke containment lines and emerged in eastern Africa. One case in Malawi in 2021 and eight cases in Mozambique in 2022 were found to be genetically linked with a 2019 Pakistan strain, which had been circulating undetected in Africa for two years.”

So, with victory in sight, Mississippi Rotarians remain in that fight. As one of those Rotarians, I am of an age to remember when polio was a present danger here. A girl in the rural church I attended was partially paralyzed and dependent on braces and crutches from polio.

But no person comes to my mind when I think of polio more than one of the most brilliant and accomplished Mississippians I’ve known who contracted polio but refused to be either bound or limited by the disease – the late Dr. Arthur Clifton Guyton. He was a genius and a marvel.

Born in 1919 to William “Billy” Guyton and wife Kate Smallwood Guyton, Arthur was the beneficiary of a strong gene pool. His father was dean of the University of Mississippi Medical School and his mother was a mathematician and physics teacher who spent five years before her marriage as a missionary in China.

As a youth, he played chess and talked in depth with Nobel Prize-winning author William Faulkner. His progression from top student in his Ole Miss class to a distinguished tenure at Harvard Medical School to a surgical residency at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston was swift and sure.

He served his country in World War II in the Navy. He contracted polio in 1946, the final year of his surgical residency. He was paralyzed in his right leg, left arm and both shoulders – and as the brilliant medical student he was, Guyton knew his dreams of a career as a surgeon were over.

But Dr. Guyton never quit. He became a globally renowned physiologist, cardiovascular system researcher, medical teacher and expert on blood pressure. He authored 40 books, including his Textbook of Medical Physiology – the world’s most widely used book of its kind. He and his wife, Ruth, raised 10 children – all of whom became doctors – in a home they built themselves.

Dr. Guyton was killed in a car accident at age 83 in 2003, still independent and still serving his fellow man. He was no one’s “victim” of polio.

But what might Arthur Guyton have accomplished without the burden of polio? That is why Rotarians worldwide keep working to eradicate polio.