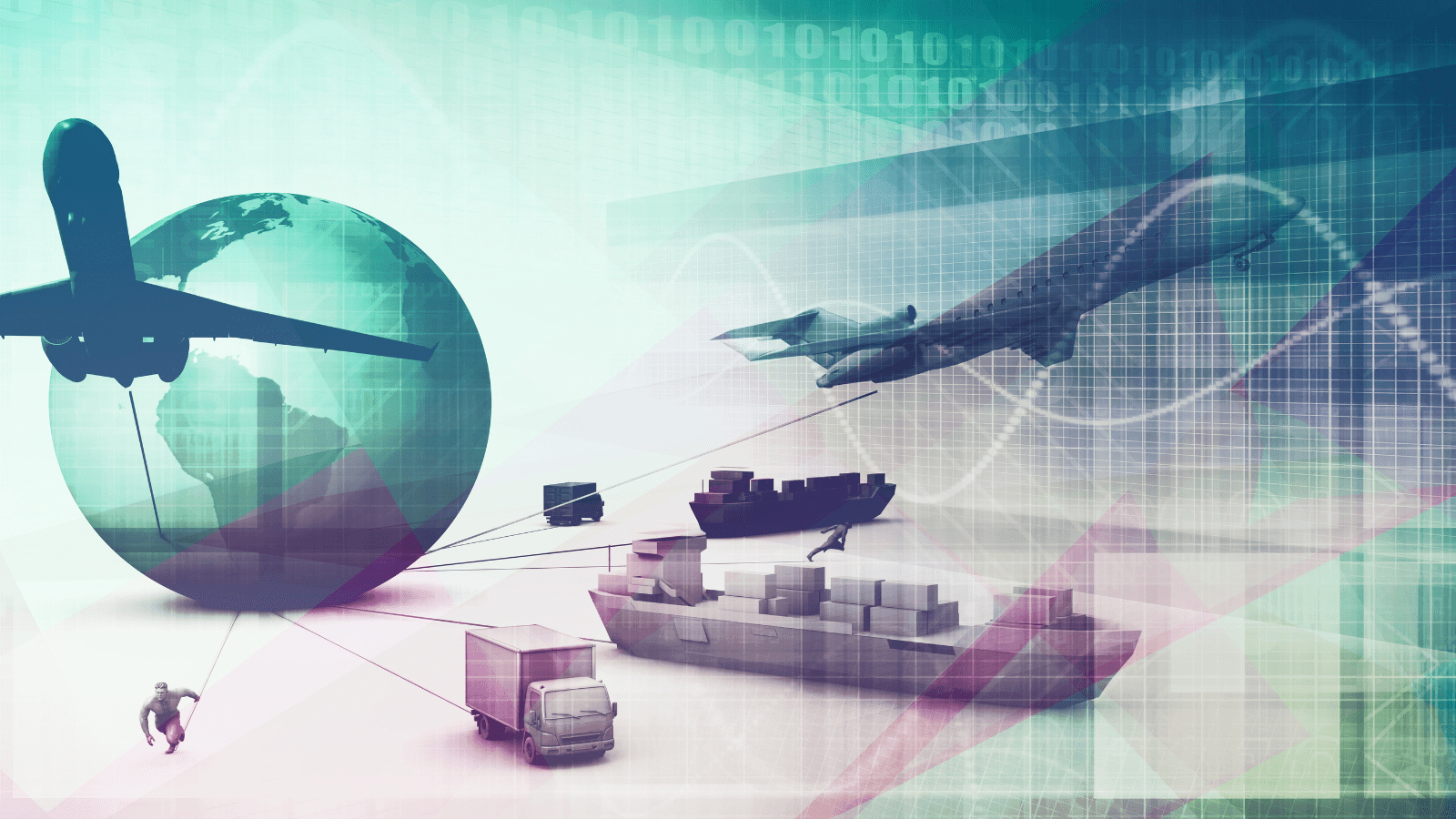

For Mississippi’s agricultural economy, global trade is vital.

Even before global headlines seized on the fact that for the first time in a half-century, China’s mammoth population was in decline, Fiscal Year 2023 U.S. agricultural trade projections were down overall and specifically down with China.

The latest information from the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Economic Research Service and USDA’s Foreign Agricultural Service analysts offered this outlook:

U.S. agricultural exports in fiscal year (FY) 2023 are projected at $190.0 billion, down $3.5 billion from the August forecast. This decrease is primarily driven by reductions in soybeans, cotton, and corn exports that are partially offset by gains in beef, poultry, and wheat. Soybean exports are forecast down $2.4 billion to $32.8 billion due to smaller production and increased competition from South America. Cotton exports are forecast down $1.0 billion to $6.0 billion based on lower unit values and subdued demand. Grain and feed exports are projected to decrease by $300 million to $46.2 billion.

Agricultural exports to China are forecast at $34.0 billion, down $2.0 billion from the August projection, due to lower export prospects for soybeans, cotton, sorghum, and pork. China is expected to remain the largest market for U.S. agricultural exports.

Why does that matter? China is the top U.S. agricultural export market with an export market value of $35.6 billion in 2021, according to USDA-FAS. Mississippi has a $9.72 billion agriculture industry. China is the third leading trading partner for Mississippi exports behind Canada and Mexico, with $759 million in value in 2020, representing a 63.8% increase over the previous year.

With one-fifth of the world’s population at 1.4 billion as the world’s most populous country, China buys food and feedstuffs on global markets to offset the nation’s limited arable lands and the dual negative impacts of pollution and climate change.

Chinese imports of soybeans, corn, rice, wheat and edible oils drive a great deal of the country’s global shopping lists as does an increasing national appetite for meat and poultry – with the widespread availability of meat (particularly for middle-class citizens) being a relatively recent development.

But economic forecasting and trade projections were both shaken in recent weeks by verified reports from the National Bureau of Statistics of China that at the end of 2022, the population of mainland China had decreased by 850,000 over the previous year.

That population decrease is believed to be the first such decline during the Chinese “Great Leap Forward” program that began in the late 1950s. Scholars saw the elimination of China’s notorious “one-child policy” in 2015 as an early signal that China’s long-term population strategy had gone awry.

Now, forecasters see India overtaking China as the world’s most populous country – and soon. The United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs said: “India is projected to surpass China as the world’s most populous country during 2023.” UN forecasts the global human population will reach 8.5 billion in 2030 and 10.4 billion in 2100.

Agricultural trade development between the U.S. and India is not yet as substantial as it is with China – and the same is true for Mississippi ag exports to India. That, despite Mississippi’s prowess in soybean production and India’s status as the world’s largest importer of soybean oil.

Those dual trade relationships are compounded by the fact that China and India are in direct conflict over which of the two nations will be the hegemon or dominant nation in Asia – and for that matter with Asia comprising more than half the global population, the global hegemon. Both China and India see themselves as competitors with the U.S. for that designation.

For Mississippi’s agricultural economy, global trade is vital, and the world has had a clear lesson in Ukraine the impacts of regional military and economic conflict on large segments of the global economy. Whether considering markets for Mississippi poultry, timber, or soybeans – and the rest of our agricultural bounty – the world is smaller, our economic fortunes are more closely intertwined than ever, and risk is an inherent facet of reward.

Global foreign and economic policy matters not just at the U.N. or the G8, but at the grocery store and the gas pumps where we live and work.