Studio portrait of Sid Salter. (photo by Beth Wynn / © Mississippi State University)

By: Sid Salter

The social and cultural ripples from the “Black Lives Matter” movement continue, from the amazing saga of the taking down of the Mississippi state flag to the ongoing debate over moving or removing monuments and changing building names on edifices named for individuals who don’t pass muster through the prism of racial justice.

One of the most discussed possible successor designs for a new Mississippi state flag is the so-called “Stennis flag” or “Hospitality flag” designed and promoted by the late senator’s granddaughter Laurin Stennis. Late in the state flag fight, Stennis voluntarily pulled her name away from her flag design when liberal critics blasted adoption of a new Mississippi flag from the progeny of someone those critics see only as a segregationist and racist.

Despite a courtly and deferential nature, the elder Stennis was in fact a proponent of segregation. He signed, and many believe was an architect of, the Southern Manifesto, the 1956 resolution condemning the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1954 decision in Brown v. Board of Education school integration case as an overreach and “unwarranted exercise of power by the court” – and pointed back to the “separate but equal” doctrine of the 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson case as the appropriate interpretation of constitutional law.

In addition to the Mississippi state flag debate, there have been national calls to revisit the Stennis name on structures including the U.S. Navy’s Nimitz-class nuclear aircraft carrier the USS John C. Stennis. and the Stennis Space Center in Hancock County, Mississippi.

In an article for the U.S. Naval Institute, titled “The Case for Renaming the USS John C. Stennis,” retired Lt. Cmdr. Reuben Keith Green cites Stennis’s record on race and challenged the Navy to rename the ship. An unrelated effort was also launched last week aims to get Stennis’ name removed from the Stennis Space Center in Hancock County, Mississippi, a NASA rocket testing facility.

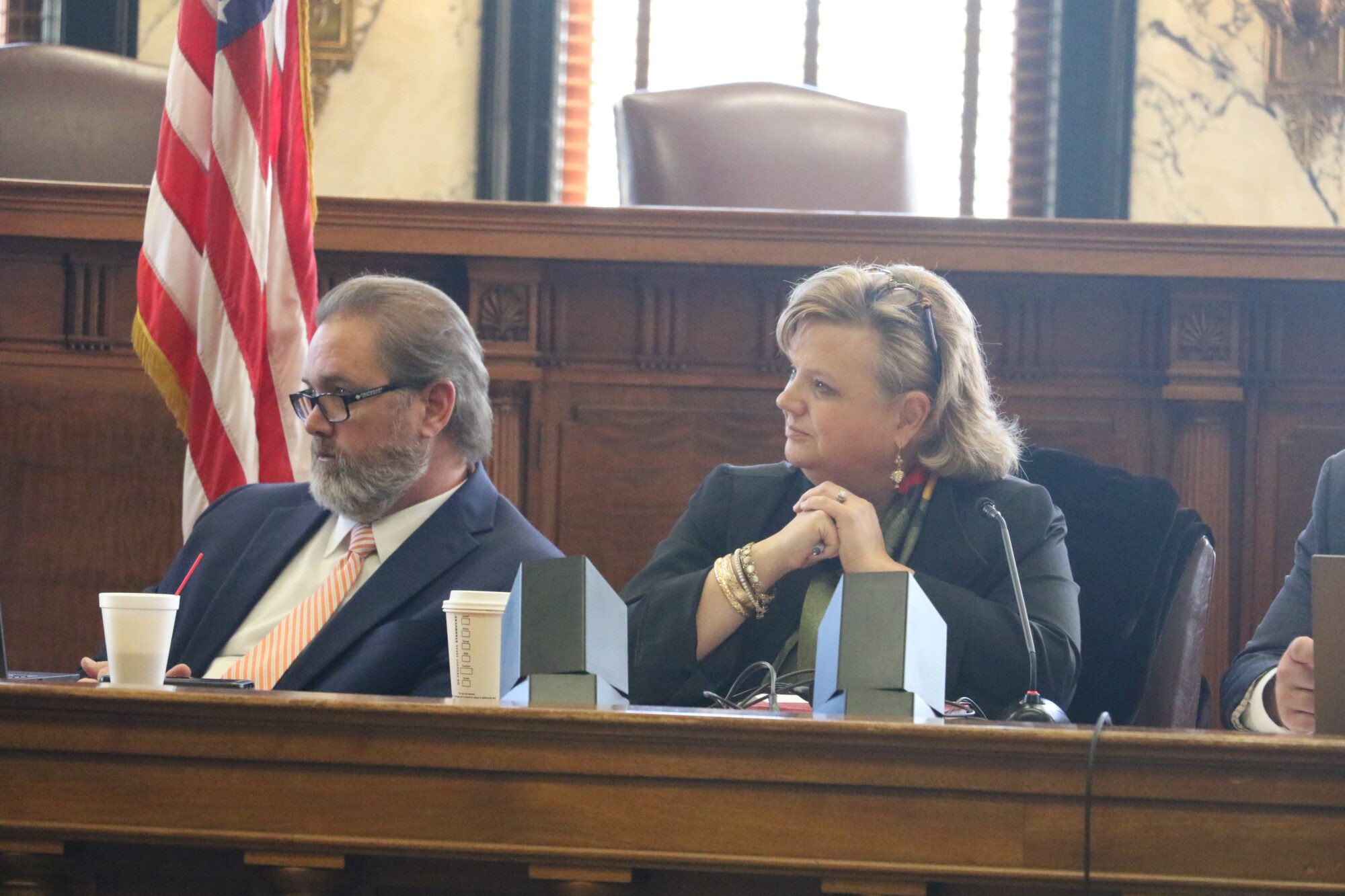

Stennis, who served in the U.S. Senate for 41 years from 1947-1989, is remembered for much more than the Southern Manifesto, which was signed by every member of Congress from Mississippi and most all congressional members in the South. Serving with eight U.S presidents, Stennis began his service with Harry Truman in 1947 and ended with Ronald Reagan in 1988.

He was elected president pro tempore of the Senate for the 100th Congress. As chairman of the Senate Armed Services Committee from 1969 to 1980, Sen. Stennis consistently supported a strong U.S. military and gained the honorary title of “the father of America’s modern Navy.”

Among his Capitol Hill peers, Stennis was known as “the conscience of the U. S. Senate” and the man who stood up to and censured Communist-baiting U.S. Sen. Joseph McCarthy.

As the chairman of the Senate Armed Services and Appropriations Committees, Stennis was the architect of the rebuilding of the U.S. Navy after World War II. Aircraft carriers got built for this country because John Stennis insisted that they be built for he knew that unlike any other asset, aircraft carriers project this nation’s military might on the world stage in an unprecedented manner.

And what are the practical political prospects of removing the Stennis name from the carrier or the NASA facility? Republican President Donald Trump has made crystal clear his opposition to such endeavors.

But if Trump is unseated by Democratic former Vice President Joe Biden, who has frequently praised Stennis as a mentor during his own Senate career, does that reconfigure the political equation?

Not likely. There is a formidable public record of Biden’s voluminous past praise of Stennis in which he expressed his deep admiration of and affection for the Mississippi senator while they were colleagues.