When a tornado ransacked north Jackson four months ago, leaving behind more than 200,000 cubic yards of debris, Jackson Mayor Frank Melton made it clear he wanted the mess cleaned up quickly.

He also made it clear whom he wanted to do it.

Documents obtained by The Clarion-Ledger show that company, Louisiana-based Nungesser Industries, walked away with the majority of the work.

Nungesser collected more than half the debris from the storm – more than five times what the contract called for – and pocketed nearly $1 million in fees. Melton had the company collecting debris before there was a contract.

The mayor praised Nungesser for its performance, but some local contractors believe they were left out while Nungesser got preferential treatment.

City Council members and state emergency management officials say the company’s disproportionate share could invite federal scrutiny of the project. The federal government has agreed to reimburse the city more than $3 million in cleanup costs.

Cedric Love of Love Construction, one of the subcontractors hired to haul away debris, said it was pretty clear Nungesser was operating with a different mandate.

“We were all given a certain section to go get and (an assigned) day for us to go get it. Nungesser just came in and flooded everything. They went wherever they wanted to go. They would come in and park right next to our equipment,” Love said. “They took a lot of money out of the state of Mississippi in a short time.”

The council awarded the debris contract to low-bidder Garrett Enterprises, a Jackson-based company run by Socrates Garrett, on April 24. The $3 million contract came with the stipulation that Garrett use subcontractors for no more than 50 percent of the debris collection.

According to that schedule, Nungesser was to pick up 10 percent of the debris.

The final tally showed Nungesser collected 55 percent of the debris and Jackson-based MAC Construction picked up 18 percent, with eight other contractors splitting the remainder. Garrett collected just 8 percent, clearing $1.5 million in collection and administrative fees.

Garrett was indifferent to the way the work was split, despite a comparison that shows Garrett Enterprises grossing $600,000 less on the contract than it would have under the original division of labor.

“The entire contract was mine, so it all came out of my end,” he said. “I don’t think I lost because of which subcontractor picked up the most.”

Melton said Nungesser earned its portion of the debris by outworking the other contractors.

Lonnie Walker of Jackson-based Longwind Construction, said the city reneged on the deal as it was explained to subcontractors by allowing Nungesser to collect debris from all over the city even if that zone had been assigned to another subcontractor.

“We all had zones and we made initial investments to do that zone,” he said. Walker said he ended up hauling about half of what he expected.

“I didn’t lose any money, but I didn’t make any either, not counting my time. If I count my time, I lost out,” he said. “It was a real bad deal for local contractors.”

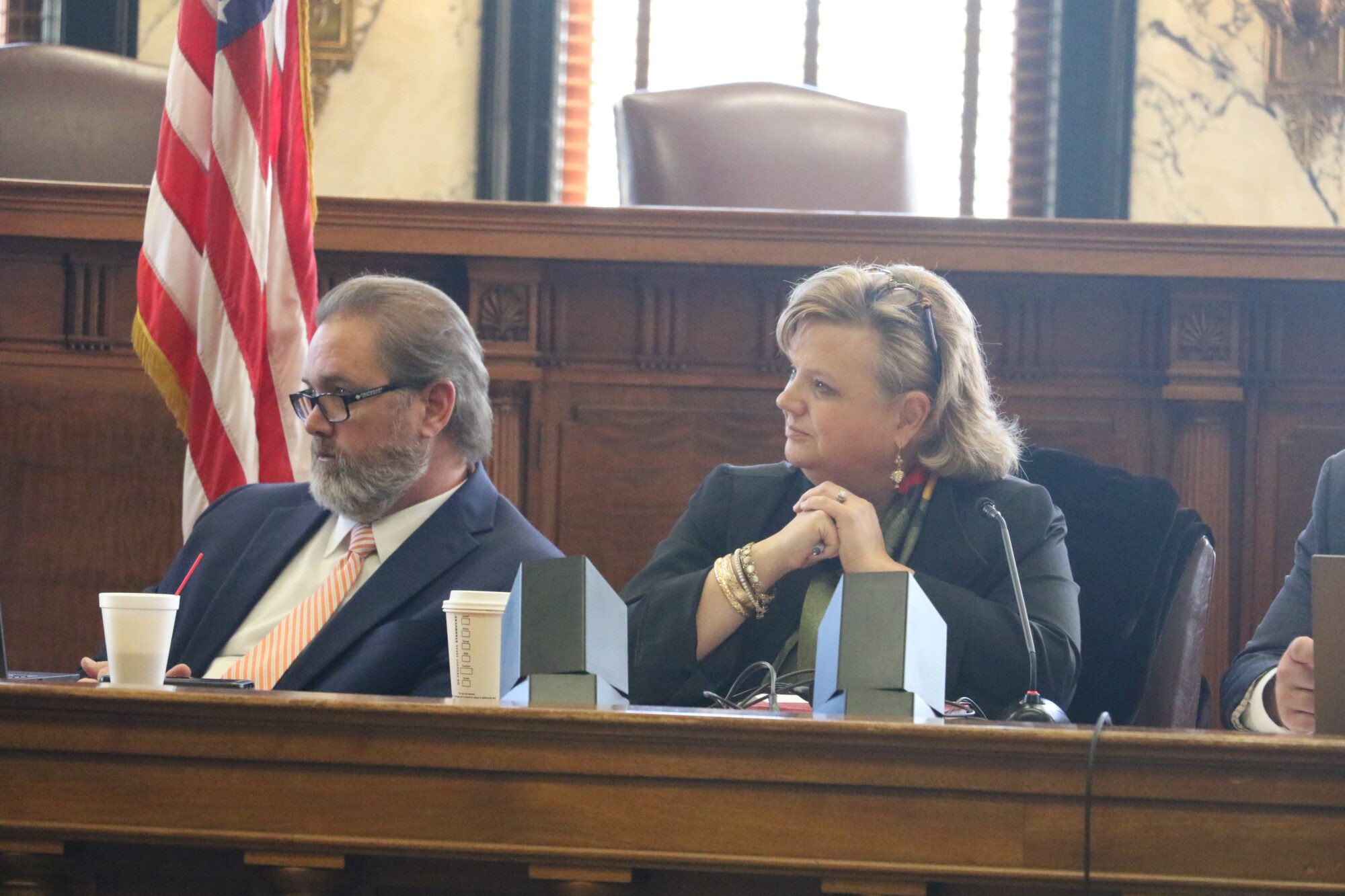

But some council members, McLemore included, publicly expressed concern about the way the mayor pushed the company, including allowing Nungesser to work in the initial days without a contract.

“Clearly there were some council members, including myself, who were displeased with the way it was handled,” he said. “The implementation part is not our role. We can raise hell, and I think that’s what we did.”

Last month, the council balked at paying Nungesser for its early work during the storm, in part because Ward 6 Councilman Marshand Crisler raised questions over whether the company had the proper paperwork to work legally in the state. In the end, the council relented and approved the $123,367 payment.

“The administration used some fancy legal language to say at the end of the day that it was OK, but forgive me if I’m not sold,” Crisler said.

The debris collection contract has ended, but Nungesser is continuing to work for the city. In June and July, the firm won several contracts to demolish vacant structures, each of which came in under the $25,000 cap that would require City Council approval.

Ward 1 Councilman Jeff Weill has expressed a lot of curiosity about the firm. How it got the work appears “unorthodox,” he said.

“My primary concern was that these repayments by FEMA are not deobligated for that reason,” he said.

Lea Stokes, chief of staff with the Mississippi Emergency Management Agency, said MEMA counseled the city to be careful with its debris contracts.

“We told them if you get this money, ‘You need to make it look like you went above and beyond to make it competitive,’ ” she said. “They left the meeting, and that night on the news the mayor was announcing who was getting the contract.”

Stokes said it is not uncommon for the Department of Homeland Security Office of the Inspector General to investigate certain contracts when they involve federal disaster money.

“There are cases even in Katrina now where the inspector general comes back and deobligates funds,” she said.

Clarion Ledger

8/3/8