Oxford, MS - February 28, 2025: The Lyceum is the administrative hub of the University of Mississippi. (Chad Robertson Media, Shutterstock)

Listen to the audio version of this article (generated by AI).

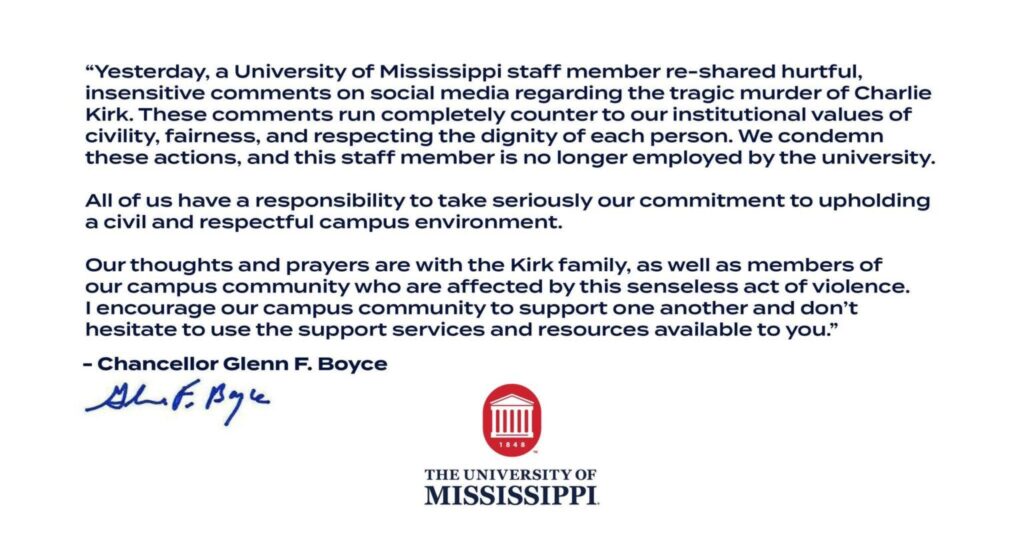

- The lawsuit alleges Chancellor Boyce violated the First Amendment rights of Stokes. The case will likely turn on the Pickering-Connick balancing test that permits a government employer to fire an employee for speech if it disrupts the function of the office.

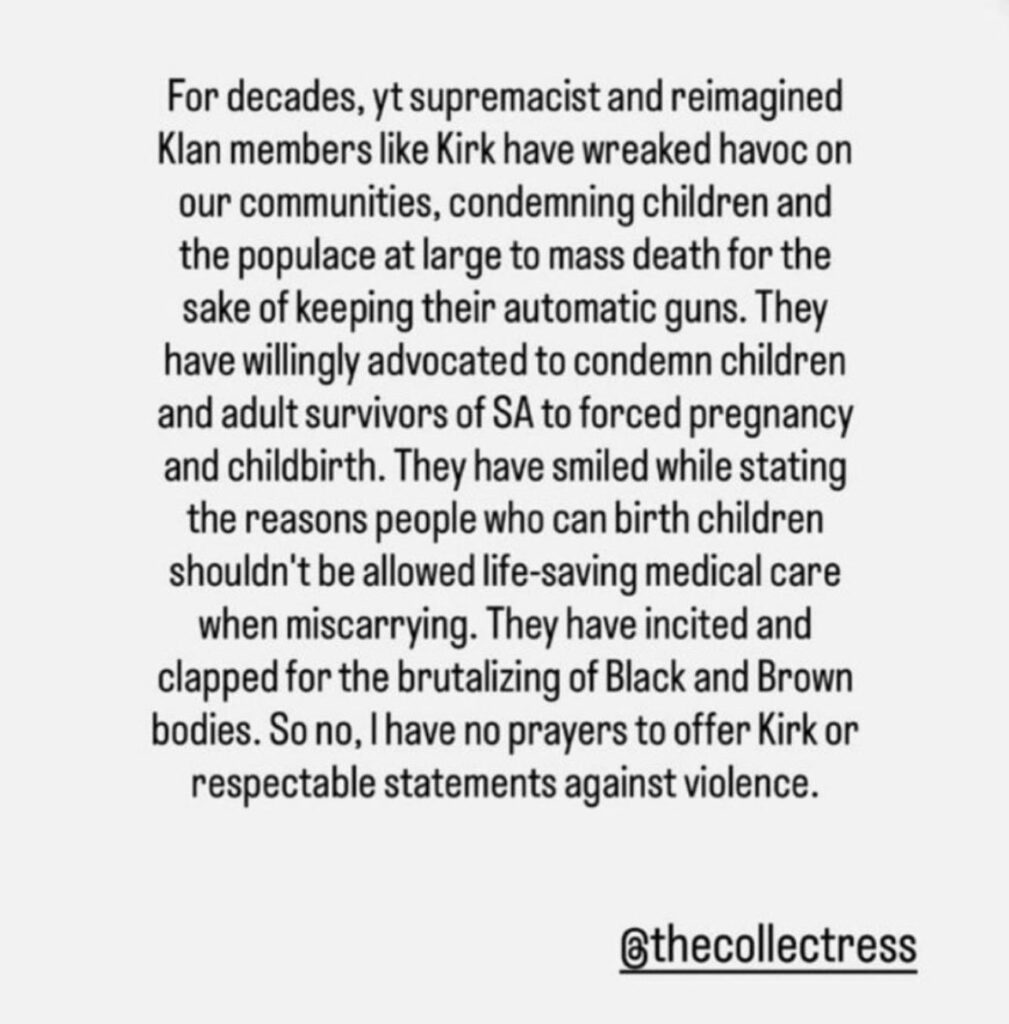

Following the assassination of Charlie Kirk on September 10th, University of Mississippi employee Lauren Stokes shared a social media post that labeled the slain conservative a white supremacist and “reimagined” Klan member, and expressed the absence of remorse over his murder:

The post sparked a firestorm that spread nationally, with millions of views on social media, across multiple platforms, and outrage directed both at Stokes and the University of Mississippi. Stokes employment, at the time of posting, was in the office of the Vice Chancellor for Development — the division of the university responsible for raising money from alumni. The original post that outed Stokes on September 10th received over 2.6 million views alone.

By early afternoon on September 11th, the University released a statement which acknowledged the social media post of Stokes, while not naming her, and indicating that she was no long employed.

On Tuesday, Stokes fired back, filing a lawsuit in the United States District Court for the Northern District alleging a violation of her First Amendment rights and viewpoint discrimination. The lawsuit was filed against Chancellor Glenn Boyce, in both his official and personal capacity, but does not name the University of Mississippi as a defendant.

The Law at Play

Once upon a time, in a land far, far away, I practiced constitutional law, including First Amendment work. Also, I stayed at a Holiday Inn last night.

Stokes’ complaint reads like a brief, complete with dramatic flourishes, cherry-picked quotes intended to demonize Kirk, and lots of cited law. The latter is abnormal at the complaint stage.

The complaint accurately cites one part of the law that will be at play here. Typically speaking, a government employee is afforded protection for private speech on matters of public concern. This is why the common refrain of “the First Amendment protects freedom of speech, not freedom from consequences” is actually only partially true. Certainly, there can be social consequences, but government’s toolset in responding to offensive speech is limited.

Stokes’ complaint devotes most of its energy on this point, arguing that her speech — the reposting of the offensive material — was done on her personal social media account and pertained to a matter of public concern, the death of Kirk.

What the complaint largely glosses over is the second part of the legal analysis at play. The U.S. Supreme Court has enunciated what is often referred to as the Pickering-Connick balancing test, named from two prominent cases, Pickering v. Board of Education (1968) and Connick v. Myers (1983). The test permits a government employer to fire an employee for private speech on matters of public concern if that speech disrupts or impairs the function of the workplace. (A copy of the complaint is attached below).

Stokes’ Complaint Introduces ‘Evidence’ Likely to Be Used by University

The complaint seemingly blames Boyce not just for Stokes’ dismissal, but for the backlash to what Stokes’ reposted. It explains that death threats were received and that a restaurant owned by Stokes and her husband received bomb threats that required them to close for two weeks and hire security.

It’s abhorrent that people’s reaction to Stokes’ post on political violence was to threaten violence in return. But it’s also asinine to attribute this to Boyce. As a reminder, the University’s statement on this matter did not name Stokes. People knew who the statement referenced because Stokes’ repost had already gone viral and generated significant backlash well before the University’s action.

What’s more, to the extent these threats occurred it was not because of her dismissal from the University. It’s almost certain that the people who were angry enough to harass Stokes over her speech were pleased she was fired. The cause of the public backlash was the content that Stokes voluntarily chose to post.

In this sense, Stokes acknowledgement of the significant disruption to her own life could, perhaps unwittingly, serve as evidence of why the University was justified in viewing her speech as disruptive to its function and operation. The ire Stokes complains of receiving for what she said would have been heaped on the University, in equal measure, had it failed to act.

This is particularly relevant given Stokes’ role within the department of the University that raises money from alumni, many of whom likely agree with Kirk’s ideology. Even among donors who disagreed with Kirk’s perspective, many would likely still not approve of spiking the football after his death. This is a problem for an institution whose lifeblood comes from raising money, particularly in situations where delay and obfuscation could be seen as complicity.

Reached late Tuesday night, a University of Mississippi spokesperson declined comment due to the active litigation.