- ‘Great Society’ welfare programs aimed at curing poverty created perverse financial incentives to avoid marriage. Government attempts at preventing fraud in the programs drove men from homes.

Sixty years ago, President Lyndon Johnson declared an “unconditional war on poverty in America.” To realize his “Great Society” vision, Johnson created a series of new welfare programs aimed “not only to relieve the symptom of poverty, but to cure it and, above all, to prevent it.”

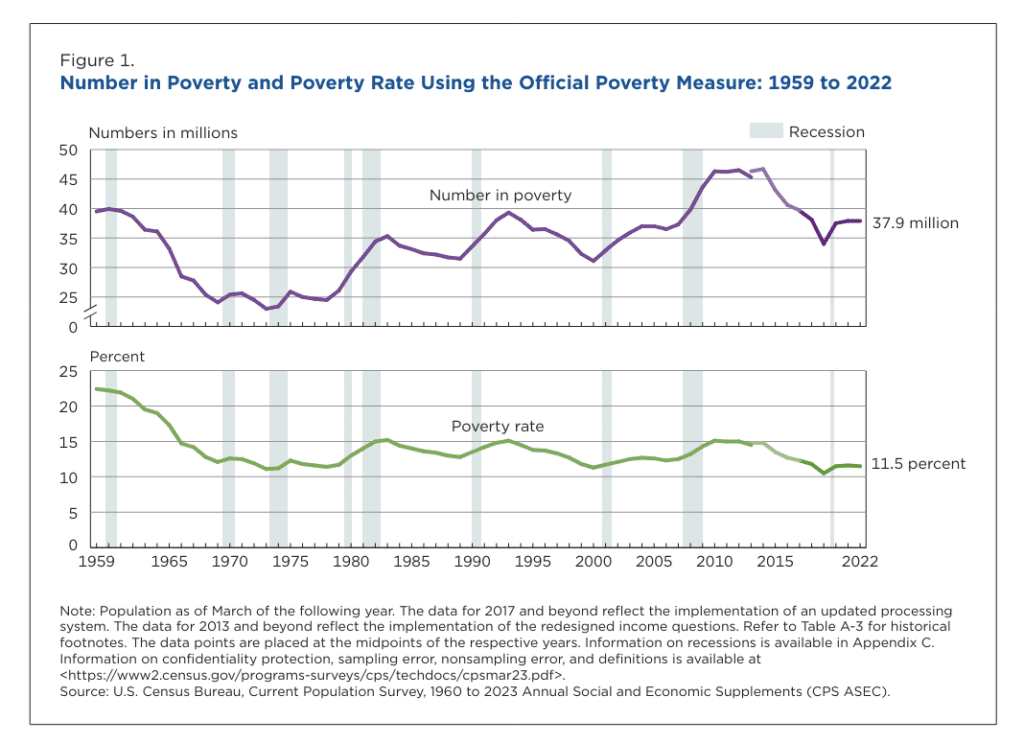

In the fifteen years prior to the launch of Johnson’s war on poverty, the poverty rate in the U.S. fell by more than half, dropping from a high of nearly 35 percent to 15 percent. The dramatic slashing of poverty rates pre-Great Society has largely been attributed to an economic boom in post-World War II America and increased labor force participation by women.

In the six decades that followed the launch of the “war on poverty,” the U.S. government spent $27 trillion on anti-poverty programs (this figure excludes Medicare and Social Security expenditures). While the programs arguably relieved some of the symptoms of poverty, they failed in satisfying Johnson’s mark of success — curing and preventing poverty.

The poverty rate declined at a much slower pace post-Great Society than it was declining pre-Great Society. Nearly half (48 percent) of those impoverished today live in deep poverty — below 50 percent of the federal poverty level.

While the “war on poverty” had a muted effect on the actual poverty rate, it has had a considerable impact on family formation, contributing to the breakdown in the nuclear family. The numbers and consequences are startling.

READ MORE: On Father’s Day, and every day, kids need dads

In 1965, 24 percent of Black infants, and 3.1 percent of white infants, were born out of wedlock. By 2022, CDC data shows 69.3 percent of Black infants, and 27.1 percent of white infants, being born to single moms.

In the 21st Century, out of wedlock birth rates have grown faster in poor and working class white communities than in the Black community.

While there is not a perfect 1:1 ratio of children being born out of wedlock living in single-parent households, there is a significant correlation. In 1950, just 9 percent of Black children lived without their father. Today, only 44 percent of Black children have a father in the home.

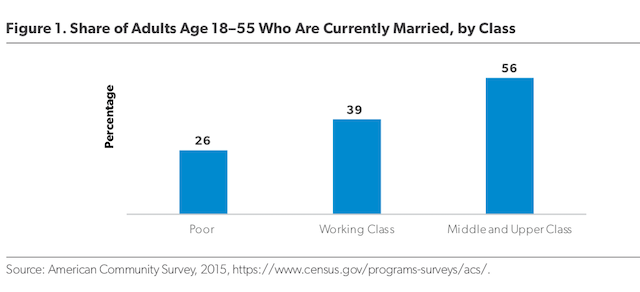

While most pronounced in the Black population, the trend is not unique to that community. Instead, the decline in marriage and two-parent households is disproportionately concentrated among the poor and the working class. Higher earners are more than twice as likely to be married as low income earners.

Source: Wilcox and Wang, The Marriage Divide, American Enterprise Institute, 2017.

So how did efforts to help the poor out of poverty contribute to the collapse of the nuclear family?

First, the Great Society’s welfare programs created economic incentives for people not to get married. Almost all welfare programs are designed with a “cliff,” a point at which the person’s income becomes too high and they lose all government benefits.

The income thresholds for welfare cliffs tend to be very low, such that a married couple, even one with low wages, likely do not qualify for assistance.

On the other end of the ledger, the benefits available to those who do qualify tend to be generous. Harvard Professor Paul Peterson says that in 1975 analysts estimated that “a household head would have to earn $20,000,” the equivalent of over $90,000 today, “to have more resources than what could be obtained from Great Society programs.”

“Once a family income crossed a specific threshold, access to these resources disappeared. Marriage to an employed male, even one earning the minimum wage, placed at risk a mother’s economic well-being,” according to Peterson.

Peterson notes that “economists and policy analysts of the day worried about the negative incentives that had been created,” but those “findings were totally ignored by those who designed public policies at the time.”

The bar to lose benefits was low, the benefits lucrative. Effectively, the government paid people not to get married. Jason Riley, a scholar at the Manhattan Institute and a columnist for The Wall Street Journal put it this way, “the government paid mothers to keep fathers out of the home—and paid them well.”

To make matters worse, efforts to tamp down the “fraud” of cohabitation, drove fathers out of the home. An entire enforcement apparatus was designed to make home visits to ensure that women receiving government welfare did not have a man living in the house.

So not only did government programs actively discourage marriage, but through enforcement, they actively created fatherless homes. While this enforcement mechanism eventually fell by the wayside, its impact lingered through norms created and passed down.