I paced the floor of my girlfriend’s (now wife’s) apartment in Oxford. Cell phone networks had failed and I could not reach my mom. Her small neighborhood of Shoreline Park in Waveland, Mississippi sat at the epicenter of what was then the worst natural disaster in U.S. history.

In the days leading up to Hurricane Katrina’s landfall, my mom had been adamant against leaving. She’d survived Camille. It would be fine. People were overreacting. Only she was wrong.

Hurricane Camille struck South Louisiana and the Mississippi Gulf Coast in 1969 as a Category 5 storm with blistering winds. I grew up hearing about its wrath in ways that made it sound almost mythical. Broken wind vanes. Houses moved blocks from their foundations. Bodies popping up out of the ground at cemeteries. As a kid, we regularly drove past the S.S. Camille, a boat that had washed ashore during the storm, on the northside of Highway 90.

Still, Katrina was a different animal. Camille was tight and compact, with an eye estimated at 11 miles. When Katrina crossed the tip of Florida into the warm waters of the Gulf of Mexico, it meandered gingerly due west. It churned and grew to satellite imagery showed a hurricane nearly as big as the Gulf itself. At the time of landfall, its eye measured 37 miles wide. Camille’s hurricane force winds could be felt 60 miles out. Katrina’s, 100 miles out. Camille moved fast. Katrina slow.

All of this meant that even though Katrina’s wind speed slowed from a Category 5 to Category 3 at landfall in Waveland, it was pushing far more water than Camille. Some estimates of the storm surge, plus waves, put the height of water that rolled into my mom’s vicinity at over 30 feet.

Further inland, the storm wreaked havoc as far north as Jackson and beyond. It generated 62 tornadoes. It caused an estimated $170 billion in property damage. And it claimed 1,883 lives.

Fortunately, my mom was not among them. At the last minute, she’d made the decision to evacuate. She left behind a lifetime of memories that were washed away when Katrina’s waters “slabbed” her house. For more than a year she’d live in a “FEMA cottage” on the property. Further east on Biloxi’s Back Bay, my sister’s home survived with flood waters rising up to her ceiling. She came home to a van in her living room and a body wedged under a nearby fence.

A few days after the storm, I made my way home with my roommate to survey the damage. His dad worked at Mississippi Power and got us past the National Guardsmen that had set up barricades at the railroad track that runs parallel to Highway 90. Once on 90, I was struck by how little I recognized. Everything had been washed clean. Few landmarks and streets signs remained. Only a debris field. Parts of Highway 90 were washed out.

Where Camille had moved houses and fishing boats, Katrina moved barges. The floating vessels that had served as foundations for Mississippi casinos made their way down and across the highway. The air was pungent with the smell of rotting chicken and wet paper rolls strewn from the port of Gulfport.

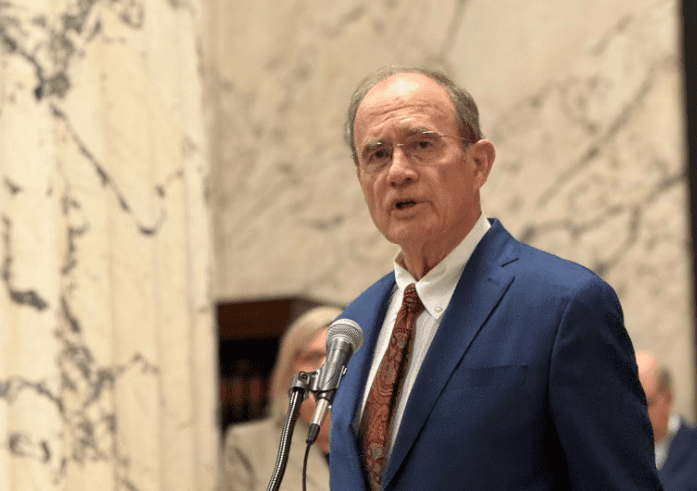

Amid all this devastation, I wondered how the area would ever recover. It seemed insurmountable. But it did. Governor Haley Barbour showed tremendous leadership in the days and months following the storm, working his connections in Washington to get aid to the Coast. Then-Senators Thad Cochran and Trent Lott had a lot to do with greasing the skids and getting federal dollars flowing.

Still, the most inspiring aspect of the recovery came not from D.C., but neighbor helping neighbor. Barbour implored Mississippians to “hitch up their britches” and get to work. Our people heeded the call. They were joined by others from across the nation — tens of thousands of churches, charities, and individuals — who brought warm meals, chainsaws, shoulders to cry on and a little bit of hope.

What we witnessed after Hurricane Katina is America’s surest strength. Adversity unifies us. When the chips are down, we are at our best. In the face of suffering, we are generous. In the face of suffering, we are resilient and gritty.

To our west, the city of New Orleans’ population was more than cut in half in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina. To this day, the population sits almost one hundred thousand people under its 2005 population.

The Mississippi Gulf Coast, in contrast, has seen its population grow across the three coastal counties. More people are employed than in 2005. There’s more industry. More development. And while there are signs of Katrina’s wrath if you look closely — monuments and memorials — you would not know the area once looked like an atomic bomb had been dropped on it.

After Katrina carved its path of destruction, Governor Haley Barbour set an audacious goal. He did not vow that the Coast would just survive, or that it would “rebuild.” He said it would come back bigger and better than ever.

There are events in our lives that shape us. They linger in the recesses of our mind, evoking emotion. For my generation, 9/11 was one of those moments. So too was Hurricane Katrina. We saw unspeakable tragedy and unimaginable goodness.

I grew up hearing about Hurricane Camille. Now my kids, born well after Katrina, hear about it. I wonder sometimes if it sounds as mythical to them as Camille did to me — if the absence of the signs of its devastation make it seem unreal. It’s hard to believe it’s been 20 years. As we mark this anniversary, we should not only remember the pain, but the strength. We persisted, rebuilt and came back bigger and better.