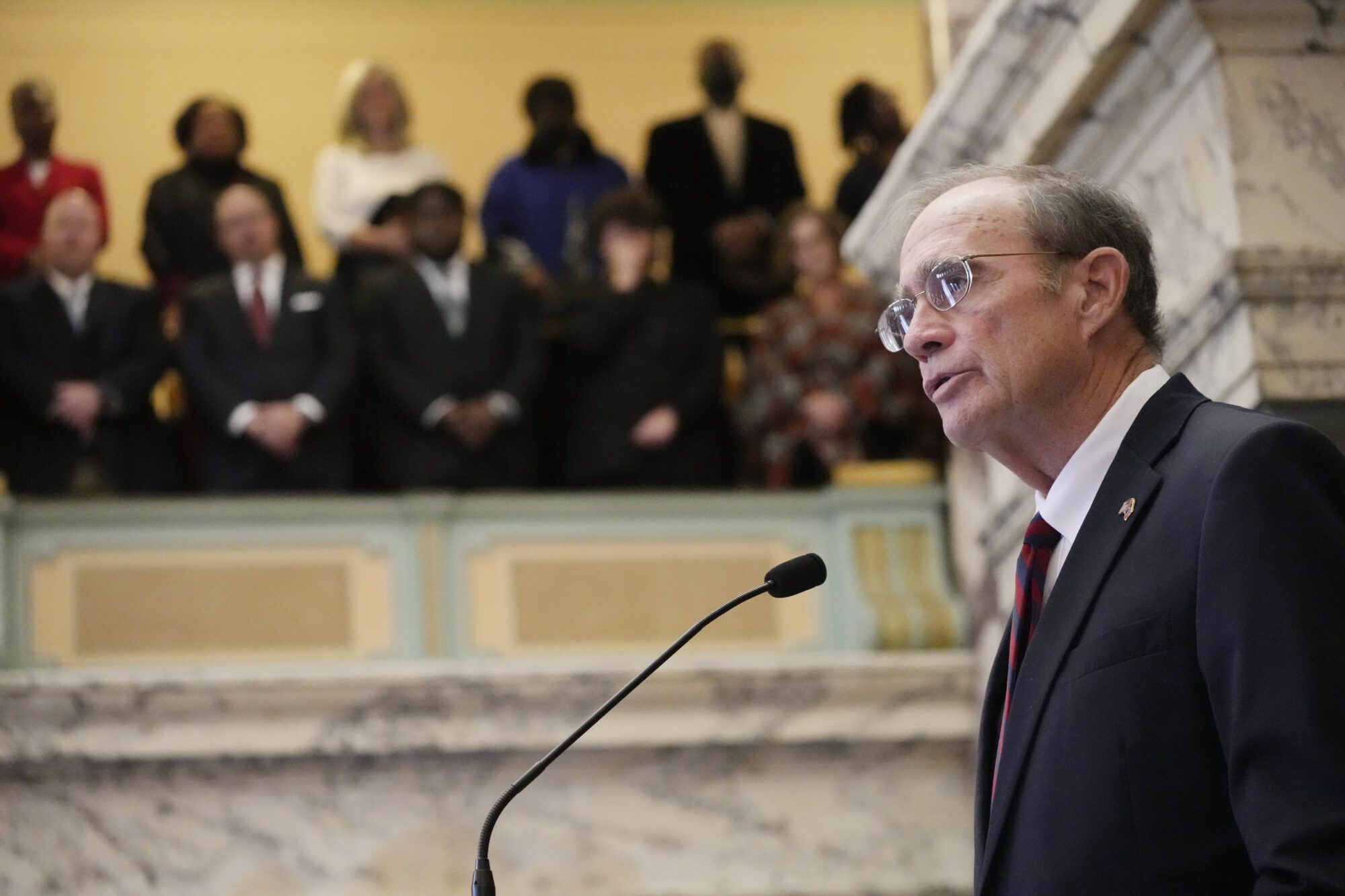

Sid Salter

- Columnist Sid Salter says nowhere are food deserts more real and visible than in rural Mississippi, and in those rural areas, none are bleaker than in the Mississippi Delta.

During Republican Gov. Tate Reeves’ time in the Governor’s Mansion, Mississippi has raised the economic development curtain on over $32 billion in new private sector investment. Much of that growth is in modern, high-tech fields that promise more and better jobs in the future.

But there are parts of Mississippi that have not yet reaped the benefits of those developments. Mississippi is still the poorest state in the union, with nearly one in five citizens living in poverty including children and under-18 teens.

No small part of that narrative is tied to hunger and food insecurity. Hunger, food insecurity and the very real scourge of “food deserts” are all verses to the same sad song. “Food deserts” are locations in which there is limited to no access to fresh foods, i.e., local grocery stores selling nutritious fresh fruits, vegetables and meats.

Nowhere are food deserts more real and visible than in rural Mississippi, and in those rural areas, none are bleaker than in the Mississippi Delta. Food deserts are defined as areas where rural residents live more than 10 miles from a grocery store.

The University of Mississippi Medical Center shared data that showed that statewide, over 70 percent of food stamp-eligible households travel more than 30 miles to reach a supermarket. Mississippi State University produced a film series on hunger in Mississippi that captured the real drama in Clarksdale when the last grocery store in that storied town closed its doors.

In food deserts, a lack of local access to fresh food does several things. It drives residents to convenience stores and fast-food restaurants, which are expensive on a per-meal basis and not as beneficial from a nutritional standpoint, especially for children.

Mississippi has little public transportation, so personal travel to supermarkets in distant communities reduces available funds for food – and many elderly citizens don’t have access to vehicles.

Into that set of problems comes the U.S. House-passed “One Big Beautiful Bill” taxing and spending package that seeks to extend Trump’s first-term tax cuts by reductions in domestic spending – including significant cuts to food stamps, formally called the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, or SNAP.

In Mississippi in 2024, the State Department of Human Services reported that 390,761 individuals received $857.8 million in SNAP benefits. The GOP bill seeks to apply work requirements to the program, which most Mississippians favor. But in total, advocates say the House bill would cut total food assistance by $300 billion.

The Congressional Budget Office estimates that the bill would remove three million Americans from the program and reduce government spending by over $92 billion over 10 years.

One group aggressively opposing the SNAP cuts is the National Grocers Association, which said in May in a statement: “SNAP provides access to fresh and nutritious food for over 41 million Americans, including over 14 million children, 1.2 million veterans, and 6.5 million seniors. SNAP funding also supports over 300,000 American jobs throughout the food supply chain and across the United States. From farmers and truckers to local grocers, for every $1 invested in SNAP, $1.79 of economic activity is generated in communities nationwide, making it a highly effective and incredibly efficient government program.”

As in other portions of the House bill, the legislation would push costs for SNAP and Medicaid from federal funding to state funding. That reality concerns several Mississippi GOP legislators, but few will speak publicly about that for fear of political reprisal.

At this point, SNAP and Medicaid – both of which impact Mississippi disproportionately due to the state’s poverty – are likely to see changes as the bill moves through the Senate. All of Mississippi’s three Republican House members voted for the bill, while lone Democrat U.S. Rep. Bennie Thompson opposed it.