- The Vicksburg native left a lasting mark on elite Paris fashion.

The first American designer to break into France’s exclusive fraternity of high fashion was Vicksburg native Patrick Kelly, who took Paris by storm in the mid-1980s. His goal was stated in his own words: “I want my clothes to make you smile.”

His clothes featured an abundance of bright mismatched buttons and colorful bows everywhere, and he was never intimidated by the status quo or the rules someone else had written. The unusual fondness for the odd buttons was a tribute to his grandmother Raney, who used to patch his family’s clothes with whatever buttons she could find. The buttons, though random and unrelated, did what they were supposed to do. They kept his clothes fastened.

An African American whose huge smile and gregarious personality revolutionized the somber serious runway traditions of the renowned Parisian elites, Patrick’s serendipitous career path reads like a bestselling novel.

Patrick, the son of a home economics teacher and a cab driver, credited his grandmother as the one who inspired his interest in fashion design. When she brought home a Vogue magazine from her white employer’s home one afternoon when Patrick was about six years old, he thumbed through it and remarked that all the models were white. He found that odd, and the thought registered that he would like to change that dynamic.

An aunt taught him the rudiments of sewing several years later. After graduating high school and a two-year stint at Jackson State University, Patrick took off to seek his fortune in Atlanta’s fashion circles. He supported himself by working in an AMVETS Thrift Store and discovered a talent for reclaiming some of the donated designer suits, dresses, and evening gowns which he modified and sold alongside some of his original designs.

A hard worker and a quick study on the who’s who of the fashion scene, Patrick made some key contacts in the fashion and modeling industry. He worked designing windows at Yves Saint Laurent. Eventually, he had his own vintage clothing store in the Buckhead district. But his big break was still illusive.

He decided to try his luck in New York City. After a disappointing year, nothing was working. Patrick was disheartened and struggling financially. As luck would have it, the despairing young man ran into an old Atlanta friend, supermodel Pat Cleveland. She had always believed Patrick had what it would take to succeed in the fashion industry. When they bid goodbye on the New York sidewalk, Cleveland says she could not get Patrick off her mind. As others had helped her in her early career, she believed in “paying it forward.” Cleveland called her travel agent, purchased a one-way first-class airline ticket to Paris in Patrick’s name, presented it to him, and said, “Go!”

Patrick was well-received in Paris from the start. His tenacious work ethic and innate creativity kicked into overdrive. In the beginning, he would buy just enough fabric to sew a few original designs, then set up flea-market style on the streets of Paris and sell his wares.

Repeat shoppers began to search for his clothing. But, even as his customers raved about his work, they were equally intrigued by his persona. He told an interviewer once, “I like to think of myself as a black male Lucille Ball. I like making people laugh.”

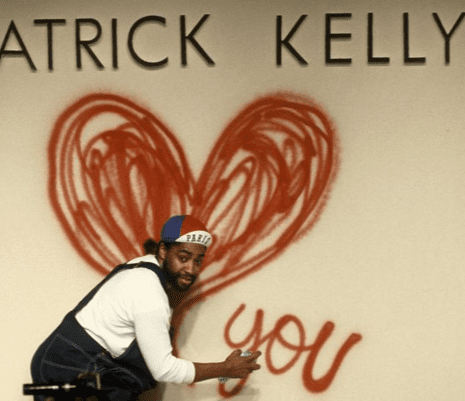

It would have been fun to be a fly on the wall in 1988, peering through the archways of the Louvre across the cobblestones where white tents were set up and the who’s who of fashion were gathered. Suddenly, Patrick Kelly, in cut-off overalls and florescent orange tennis shoes, burst onto the runway and, without a word, slowly spray-painted a huge red heart on a white backdrop. This would become his way of opening all of his shows.

As the crowd turned to stare, rock music blasted through the speakers, and spotlights thrust their, beams on six-foot-lithe models striding down the runway in whimsical, brightly colored “happy” clothes. The atmosphere was transformed from stiff to playful. The critics called that show “refreshing.”

The most refreshing fact of all is that Patrick had achieved what other Americans had failed to achieve, and he had done so by being true to himself.

Patrick was born in 1954. He had lived in the segregated South and experienced the Civil Rights struggle firsthand. It would have been easy to blame some of his early career obstacles on discrimination. But he never did play that card.

His clothing carried prominent symbols of his race and culture, such as cartoonish watermelon wedges, black baby dolls, golliwogs, and other references to Black folklore. Was it that he could laugh at himself, or did he have a certain respect for his own story? His longtime business partner and life partner, Bjorn Amelan, once said in an interview that those symbols lost their power to shame or stigmatize when Patrick was able to use them as he did.

During an exhibition of Patrick’s clothing in a posh New York boutique, he had constructed a display of American Black cultural symbols. A well-meaning lady told him she did not appreciate images of Aunt Jemimas because they reminded her of maids. Patrick was polite but retorted, “My grandmother was a maid, honey. My memorabilia means a lot to me.”

Among Patrick’s iconic customers who became close personal friends were Goldi Hawn, Isabella Rossellini, Jane Seymour, and the late Bette Davis. Their friendships were solid and founded on mutual respect, love for laughter, and shared stories.

Patrick had finally achieved financial success and was poised to make a name as big as any legendary designer had ever been able to achieve. On New Year’s Day, 1990, at the age of 35, Patrick passed away from complications of AIDS. He is buried in Paris in Perè-Lachaise cemetery.