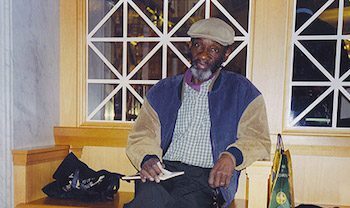

Ahmos Zu-Bolton (Photo from the African American Registry)

Through his work, Zu-Bolton became one of the leaders of America’s Black arts movement.

An ardent admirer of Ahmos Zu-Bolton and his work wrote that the Poplarville native “never postured for the spotlight. He didn’t need to. He was authentically Ahmos, and there will never be another man like him.”

Born in Pearl River County in 1948, Zu-Bolton grew up in DeRidder, Louisiana, cut sugarcane on Gulf Coast plantations, helped integrate Louisiana State University in 1965, and served a draftee’s four-year tour of duty in Vietnam. After the Army, he earned a bachelor’s degree from California State Polytechnic University in 1971 and a master of fine arts in creative writing degree from the University of Iowa.

That rich background of experience positioned him to become a poet, playwright, journalist, editor, activist, publisher, teacher, bookstore owner, and author of three books: A Niggered Amen: Poems, Synergy D.C. Anthology with coauthor E. Ethelbert Miller, and Ain’t No Spring Chicken: Selected Poems. He also wrote several plays, including The Widow Paris: A folklore of Marie Laveau, The Funeral, Family Reunion, and The Break-In.

Grace Cavalieri, a fellow poet, playwright, and Library of Congress radio host, wrote that “Zu-Bolton’s work is his version of history. He knew his life and experience were too important to leave to other people. He created worlds and populated them with people to act out the blood and pulse of being black in America.”

Cavalieri credited her friend with wanting “to break down the true nature of things, and in doing this he offered a magnificent example of himself, his culture, and his self reason.” She said that he “wrote with intelligence, purpose and style and he knew he had a mission.”

Through what Cavalieri called their “being young together” in Washington, DC, she said Zu-Bolton “wrote to tell a story. He wrote to know himself and change his mind. He wrote to change other people. He wrote about the effect of the century on his people. He wrote to tell every good thing he could find and everything bad that threatened it. He taught us to give up control about outmoded ways of seeing the narrative poem. He brought folktales to modernity. He fought the wars that are inside of all of us. This warrior, Ahmos, achieved great victories in battle and literature without hurting anyone.”

Through his work, Zu-Bolton became one of the leaders of America’s Black Arts Movement. For a decade from the mid-sixties to about 1975, those artists and intellectuals involved in the Movement focused on music, literature, drama, and the visual arts. Theirs was the cultural sector of the Black Power movement. Self-determination, political beliefs, and African American culture drove their work, but both the Movement and Black Power faded when several leaders moved from nationalism to Marxism.

Zu-Bolton founded Energy BlackSouth Press, edited the literary journal Hoo-Doo, and co-edited an innovative journal on cassette tape called Black Box. He co edited an anthology (with E. Ethelbert Miller), called Synergy D.C. (1975). In the late Seventies, he also organized a series of Hoo-Doo Festivals, which presented poets and musicians in New Orleans, Galveston, Austin, Houston, and other cities.

In 1983, when just thirty-five years of age, Zu-Bolton moved to New Orleans, where he established the Copasetic Community Book Center, which served both the literary and community theater movements. Penny’s Poetry Pages reports that for its ten years of existence, until 1992, the bookstore was an active venue for literary events, presenting plays, poetry readings, children’s programs, and workshops for young writers.

While living in New Orleans, the entrepreneur also taught English, African American studies, and creative writing classes at Xavier University, Tulane University, and Delgado Community College. He was visiting writer in residence at University of Missouri. A journalist, he contributed articles to the New Orleans Times-Picayune and the Louisiana Weekly.

In his poems published by the Voice Foundation in 1988, from “Taxi Cab Blues,” in what he himself called neo-urban folklore, Zu-Bolton wrote this:

There is a cure for the Blues

[…]

A white cabbie says there

ain’t never been no/great

colored poets

[…]

and I think to myself

man this cat is hip/ smooth,

there’s truth in his meter,

so I sez to him I say, hey man,

how come a professor

like you is

driving a cab?

Concise Oxford Companion to African American Literature states that “Zu-Bolton’s free verse poems — collected in A N*ggered Amen (1975) — employ African American vernacular speech and are sometimes cast in the form of dramatic monologues or modeled on the sermonic Tradition.”

Zu-Bolton died of cancer in March 2005 at Howard University Medical Center in Washington, DC.