The Cross and the empty Tomb belong together. The former, coercive. The latter, liberating. Together – lifechanging.

The death of Jesus is one of the most consequential moments in human history. And, like all consequential moments, there is always plenty of perspective surrounding the significance, in this instance, of the blood, the impact of the sacrifice for our lives, the necessity of such a cruel demise and, of course, plenty of theological interest in atonement theories.

But something has been haunting me for some time now; something little talked about but divinely effective for those who find themselves captivated by Jesus hanging on the Cross. I call it “coercion theory.”

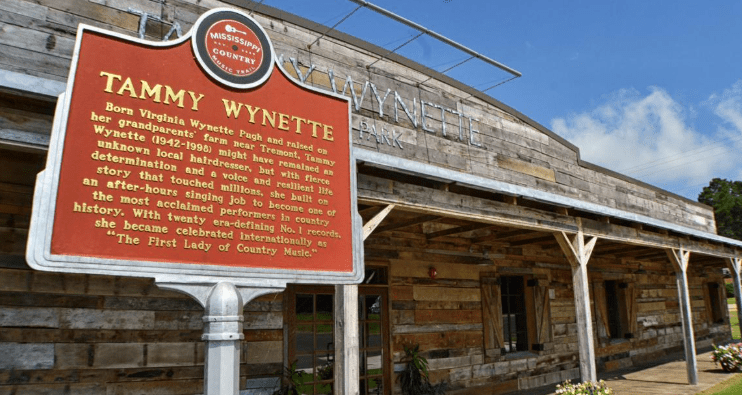

Lee Eclov talks about a board game his family used to play in the mid-50s put out by Parker Brothers. It was called “Going to Jerusalem.” Each player was represented by a plastic disciple with robe, sandals and a staff.

With a roll of the dice you looked up answers in a little New Testament. You started, of course, in Bethlehem and proceeded through places like Nazareth, Capernaum, Bethsaida, the stormy seas, Bethany and the Mount of Olives. You could, if you were winning, make it all the way to the triumphal entry into Jerusalem.

But the journey stopped there.

But there was no suffering. No enemies plotting your death. No Roman gibbet. No death. You made your way through the nice stories and skipped right over “Deny yourself, take up your cross and follow Me.”

It was a fun night like too many of us like our Christianity – a good time with beverages, chips, dip and great conversation mixed with laughter. But no blood. Goodness, no.

There was no persuasion principle in play.

Methodist missionary E. Stanley Jones lived in India at the time of Mahatma Gandhi who, among many other things, showed the power that suffering and self-denial could exercise upon a people. Interestingly, what Jones wrote in a portrayal of Gandhi after his assassination proved motivating to Martin Luther King, Jr. and his efforts in non-violent resistance. At any rate, when things weren’t going the way Gandhi thought they should he would frequently go on a hunger fast until his admirers acquiesced to his will. Some of these fasts lasted only a few days but some for weeks and Gandhi’s seeming coming death by starvation was enough to bring to sobriety those drunk on having their selfish way.

So Jones, considering the fasts of Gandhi, told the story of a young Indian lady who went to the West to get an education and also got something else – an addiction to alcohol. Measures were taken but she seemed beyond all reasonable efforts to reform her. And so, her father began a fast until either death or change. Horrified at the prospects of someone dying for her, she repented.

And her testimony was this: “Someone had to suffer to redeem me.”

It was argued at the time that the father’s method sounded terribly coercive. The response from the father? “The same kind of coercion that Christ applies to you from the cross.” It’s true, to know that God became flesh and felt it necessary to suffer and die for my sin-sick sole certainly ought to have some kind of coercive effect.

John Newton wrote many hymns, among them, Amazing Grace. His tombstone best told his story in brief, however: “John Newton, Clerk. Once an infidel and libertine, a servant of slaves in Africa was by the rich mercy of our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ preserved, restored, pardoned and appointed to preach the faith he had long laboured to destroy…”

One of his hymns talked about the coercive power of the cross:

In evil long I took delight

Unawed by shame or fear,

Till a new object struck my sight

And stopped my wild career.

I saw One hanging on a tree,

In agonies and blood,

Who fixed his languid eyes on me

As near his cross I stood.

Those “languid eyes” are never more apparent than during Holy Week, the days where Jesus seemingly look down on us again from the Cross and coerces us to turn from our wickedness and by grace embrace His goodness.

We shout victory and resurrection on Sunday, but always remembering those languid eyes that are premier tools of the faith to alleviate the brokenness of the world – our brokenness.

The Cross and the empty Tomb belong together. The former, coercive. The latter, liberating. Together – lifechanging.