Sid Salter

Until federal court intervention, the Parchman farm was operated as a state-owned plantation farming operation with a strong profit motive.

I attended a portion of the Mississippi Historical Society annual meeting on Friday at the “Two Museums” complex near the Mississippi Department of Archives and History in Mississippi’s capital city. Jackson has received a significant share of negative national media attention over the last decade for a myriad of problems.

But the “Two Museums” – the Museum of Mississippi History and the Mississippi Civil Rights Museum – remain modern monuments to what can be in our state. They are also places that are repositories of lessons Mississippians should have learned together over the last century – lessons about race, poverty, injustice, courage, accomplishment and potential that are at once realized and unrealized.

The Mississippi Historical Society is an organization in which conversations and scholarship about Mississippi’s bewildering history have continued and flourished. This year’s annual meeting focused on women in our state’s history, Mississippi’s environmental history, and 20th Century Mississippi history.

There were several outstanding presentations, including an incredible look at the “Operation Chlorine” episode in which a barge carrying two million pounds of deadly liquid chlorine sank in the Mississippi River near Natchez in 1961.

The ensuing and harrowing efforts over the next 18 months to safely raise the chlorine tanks engaged President John F. Kennedy and Mississippi Gov. Ross Barnett at a time the pair were actively skirmishing over the admission of James Meredith as the first Black student at Ole Miss and that Kennedy was simultaneously locked in unprecedented nuclear brinksmanship with Russian premier Nikita Khrushchev during the Cuban Missile Crisis.

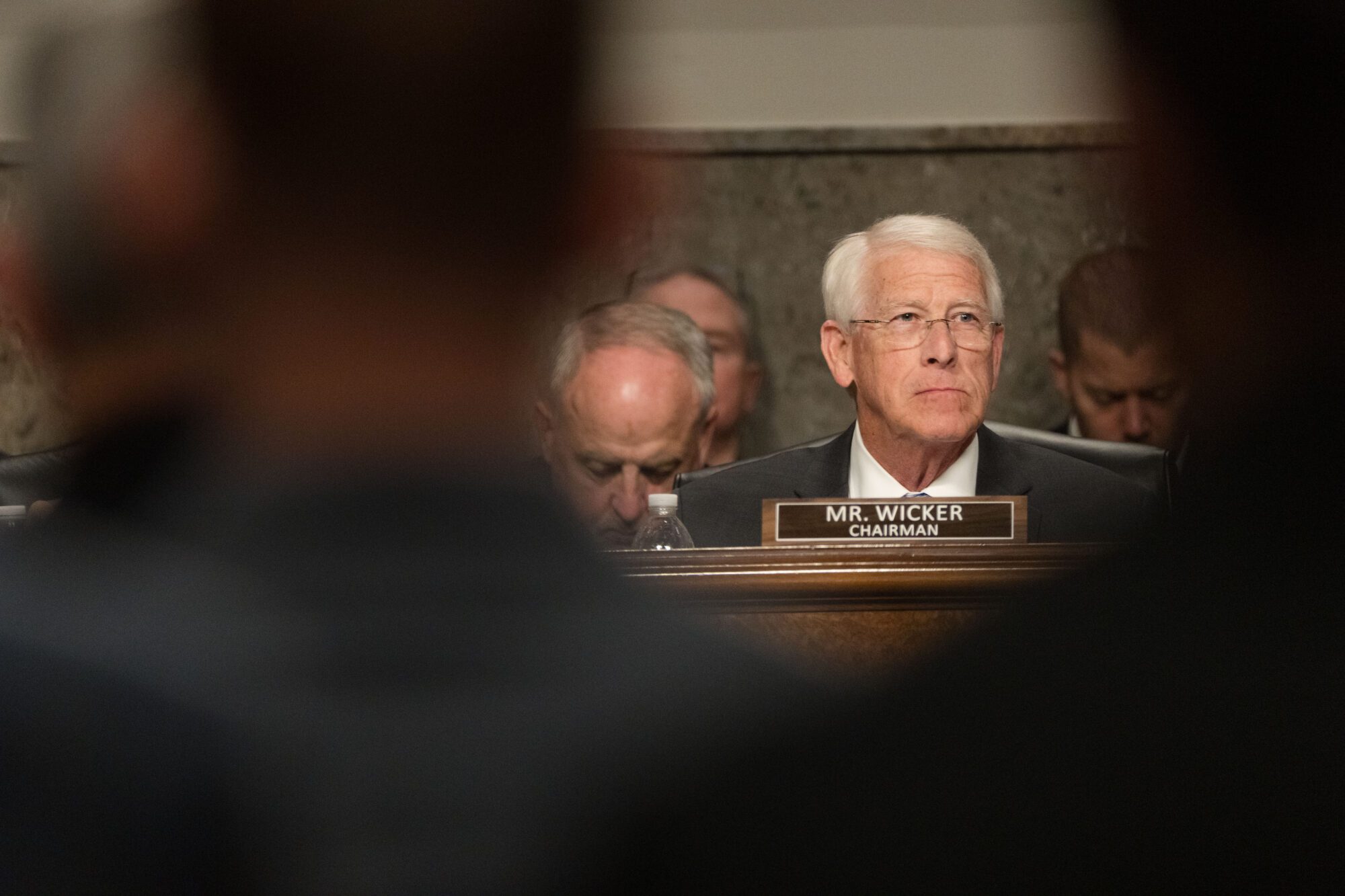

But as one who spent a significant amount of time covering issues at the Mississippi State Penitentiary at Parchman and the politics of corrections at the Mississippi Capitol in Jackson – and as a proud father – I was particularly interested in a presentation by archivist Kate Salter Gregory on the personal and judicial papers of the late U.S. District Judge William Colbert Keady of Greenville.

There was a time in Mississippi – and also in Alabama, Arkansas, Louisiana and Texas – when the state’s prison inmates in great measure ran the prisons. In those days, inmates working in the cotton fields at the sprawling 20,000-acre Parchman prison farm complex in Sunflower and Quitman counties in the Mississippi Delta were routinely guarded by armed trusty inmates on horseback who had “shoot-to-kill” authority from prison officials should an inmate make a run for freedom.

More than trusty inmates simply manning gun posts in the cotton fields, trusties also ruled the prison dormitories by night. The inmate “cage bosses, floorwalkers, and hall boys” were in those days allowed to mete out their own justice to fellow inmates away, primarily, from the prying eyes of prison staff.

Until federal court intervention, the Parchman farm was operated as a state-owned plantation farming operation with a strong profit motive. The bottom line was that making a profit for the state on the cotton, row crop and livestock harvests was encouraged. Observance of modern trends in enlightened penology was not.

For those prisoners who would not toe the line, there were torturous beatings with the leather strap called “Black Annie.”

In his 1988 book All Rise: Memoirs of a Mississippi Federal Judge, Keady recounted his long involvement in efforts to reform the Mississippi prison system from the measured view of a veteran federal judge.

“The court found that the physical facilities were in such condition as to be unfit for human habitation, that racial discrimination was practiced by the penal authorities in the assignment of inmates, that the medical staff and hospital facilities available to penitentiary inmates were far less than minimal, and that the inmates, under the protection of few free-world personnel, had to work under guns placed in the hands of other inmates who were trusties. Many evils in the trusty system were documented by the evidence. The court found that a complete lack of proper disciplinary rules for inmates regarding prison misconduct existed and that a proper system of punishment and hearing procedures did not exist.”

Keady’s decision in the landmark Gates v. Collier case outlawed racial segregation and the trusty system in prisons, ending what historian David Oshinsky called in his writings about the old Parchman Farm prison “worse than slavery.”