Imagine if state government decided how many car dealerships were allowed in Mississippi.

Consumers would suffer as their choices would be limited compared with an unregulated system where auto dealerships could be built anywhere by anybody.

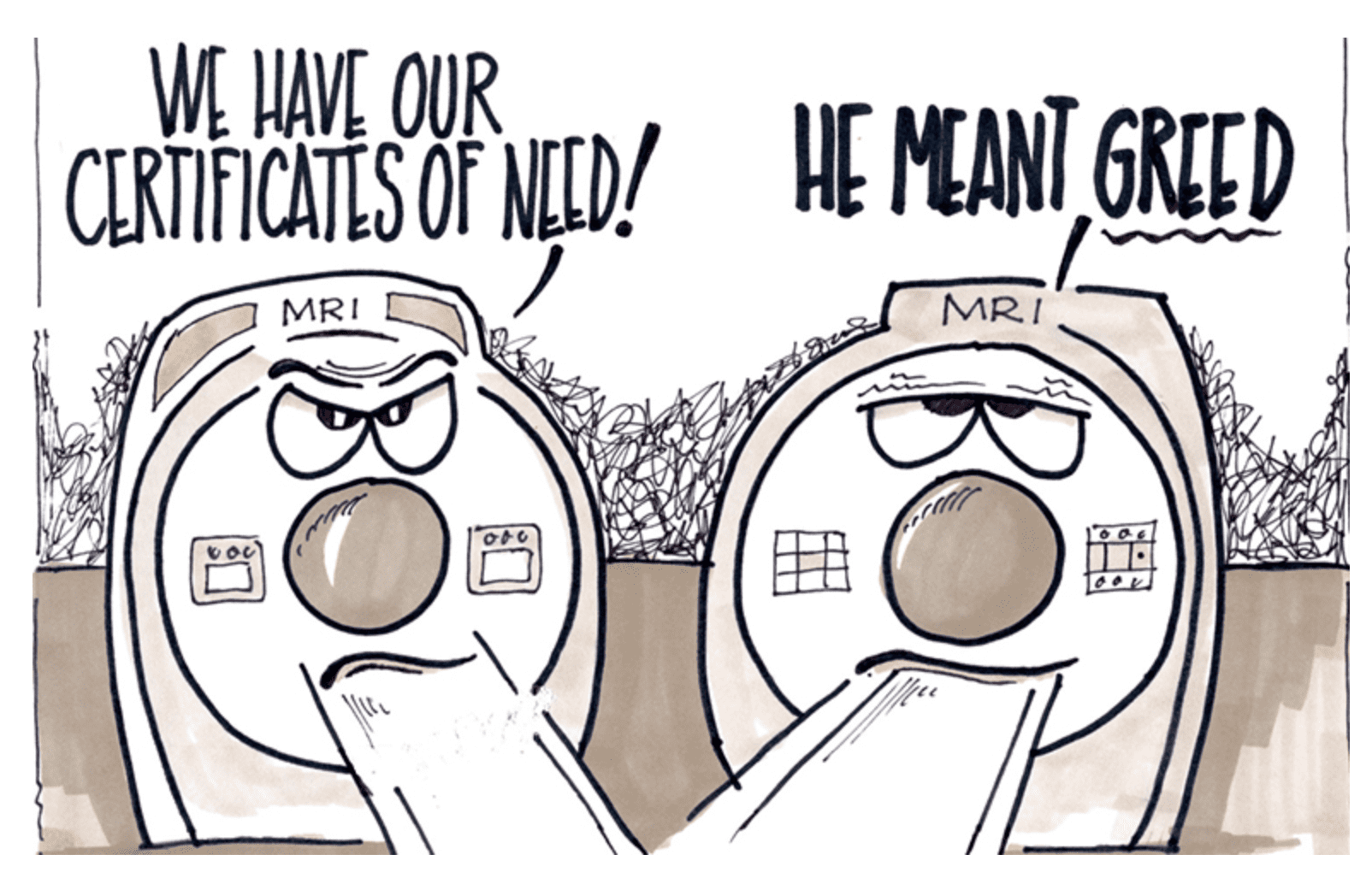

Mississippians now live and die in a healthcare system where the state Department of Health controls the supply of hospitals, clinics, diagnostic equipment, nursing homes and even home health providers. The rationale behind this system, known as Certificate of Need (CON), is that it will prevent unnecessary duplication of services and higher costs due to this duplication.

Some History: Certificates of Need began as part of the National Health Planning and Resources Development Act of 1974 that was signed into law by then-President Gerald Ford. The act was intended to curb big increases in federal healthcare spending and one of the cost control measures was to require states to institute CON laws to regulate the supply of healthcare facilities.

Thirty-five states still have some sort of CON laws of varying restrictiveness. Mississippi and nearby states have substantial CON regulations with Mississippi having 35 laws that govern its Certificate of Need Program.

Mississippi’s CON Program now regulates hospital beds, nursing home beds, inpatient psychiatric beds for children, chemical dependency beds and home health services.

The CON structure is a command and control system, not unlike the fascist regimes where government instead of the marketplace determines the allocation of resources and means of production. Unfortunately, limiting supply done to control costs often results in increased prices to the end user.

According to several studies by the free-market Mercatus Center at George Mason University, states with Certificate of Need regulations have 99 fewer hospital beds per 100,000 residents than non-CON states and have fewer diagnostic machines — 2.5 fewer hospitals providing MRI services than non-CON states.

A goal of CON regulations is to ensure access for underserved rural communities, but 25 years of data shows CON regulated states have 30 percent fewer rural hospitals per 100,000 residents. Additionally, according to a national report of rural hospitals, 48 percent (31 out of 64) of Mississippi’s rural hospitals are at high financial risk. Nationally, 21 percent are listed in danger of closing their doors.

The Obama administration was also in favor of eliminating Certificates of Need. A position paper, jointly written by the Federal Trade Commission and the Department of Justice and requested by South Carolina state officials in 2016 says CON laws interfere with market forces that can better determine the proper supply of facilities and services.

In short, the consequences of CON regulations include suppression of supply, misallocation of resources and the shielding of health care providers from competition that improves performance.

An example of this took place in Madison, one of the fastest growing cities in the state where St. Dominic’s Hospital sought to build a new facility in 2009 but was denied by state officials. The case ultimately went to the state Supreme Court which upheld the denial in 2012.

The fatal flaw in CON regimes is its willingness to protect incumbents under the assumption that all providers are equal and effective. Competition with the “invisible” but well informed “hand of the market” is a powerful tool in providing cost efficient services to healthcare consumers.

If Mississippi wants a financially healthier healthcare system, eliminating the Certificate of Need structure would be a great first step in the right direction.