As a matter of public policy, lawmakers should be aware that every time they create a new law that the police must enforce, they raise the risk of conflict that puts officers in danger.

In 1962, President John F. Kennedy declared this week ‘National Police Week,’ in honor of those officers who paid the ultimate price in the line of duty.

There are many who deserve that honor in Mississippi. As a state, we have experienced 331 law enforcement deaths in the line of duty since records have been collected. There are likely more that evaded historians.

Behind each of these numbers is the name of a fallen officer.

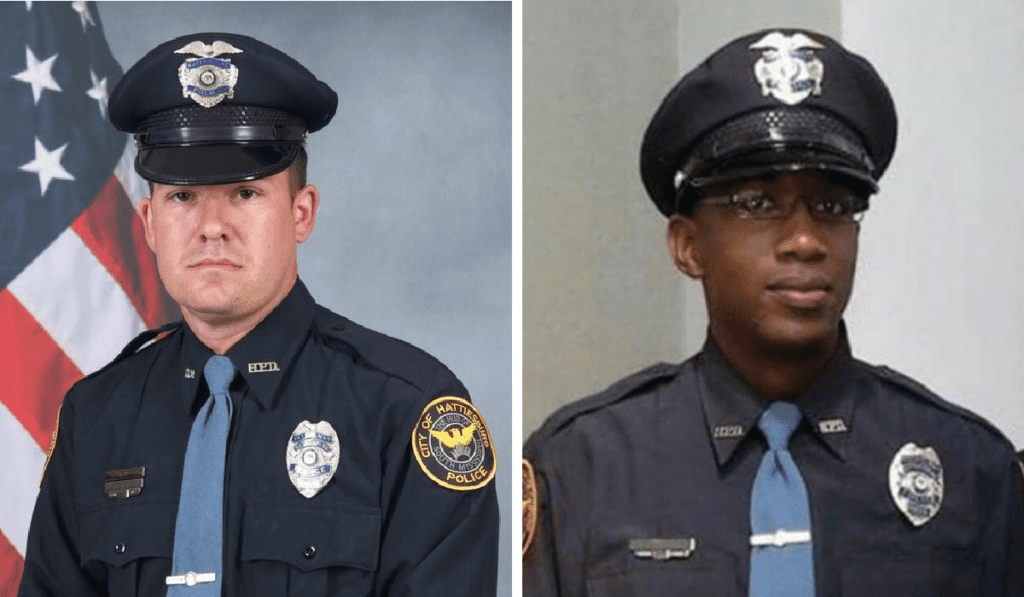

Patrolmen Benjamin Deen and Liquori Tate of the Hattiesburg Police Department were both shot and killed after a routine traffic stop turned violent on May 9, 2015.

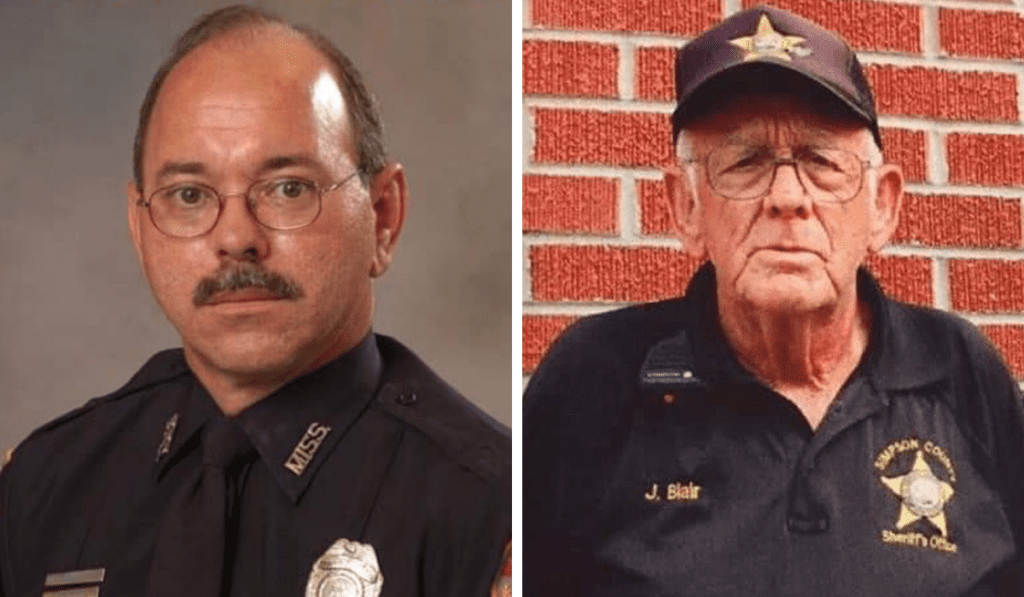

Biloxi Police Officer Robert Stanton McKeithen, a 24-year veteran of the force who was planning retirement, was killed in the parking lot of a police station. A man simply walked up to him, with no provocation, and shot him multiple times on May 5, 2019.

Then there is James Harold Blair, a Deputy Sheriff in Simpson County and beloved community figure. Deputy Sheriff Blair had been in service for 50 years. He was shot and killed when a psychiatric patient he was transporting wrestled his gun away.

In December of last year, Bay Saint Louis Police Department Sergeant Steven Robin and Officer Branden Estorffe were shot and killed around 4:30 a.m. while conducting a welfare check on a woman and child sitting in a vehicle parked at the Motel 6 at 1003 U.S. 90. Estorffe was just 23-years old.

Not all officer deaths are the result of intentional acts of violence. In 2021, State Trooper John Martin Harris, a 24-year veteran, was struck and killed by a semi-truck while performing a traffic stop in Madison County. In 2022, Lee County Officer Johnny Patterson was run over while directing traffic outside of Shannon Primary School.

Some of these men were officers for a short time, others a lifetime, but they all served their communities honorably. They put themselves in danger for the wellbeing of others, in some cases knowingly rushing into the breach. Each left behind family—wives, sons and daughters, mothers and fathers, sisters and brothers, and grandchildren.

Over the last few years, law enforcement has come under intense public scrutiny. The deaths of Michael Brown, Eric Garner, Philando Castile, Breonna Taylor and George Floyd all sparked outrage and led to serious questions about training, race relations and accountability. As protests started to unfurl across the country, extremists seized the moment to demand that communities “defund the police.”

Police officers are people, which means they make mistakes and sometimes even do bad things. Imbued with the power of life and death, they carry a heavy responsibility to use it in a way that maintains public trust. When they engage in misconduct, they should be held accountable. But it is important not to exploit individual incidents to impugn the integrity of an entire profession.

For every one tragic officer-involved incident, there are thousands of positive interactions that receive no attention. There are men and women in blue who stop to change a tire and who perform wellness checks on elderly citizens. They respond when something has been stolen or when there is a bump in the night. And every time they get dressed to go to work, they know they might not be coming home. This is an apprehension most of us do not carry to work.

As we honor the sacrifice of brave law enforcement this week, it is worth mentioning that we can do so all year round. As a matter of public policy, lawmakers should be aware that every time they create a new law that the police must enforce, they raise the risk of conflict that puts officers in danger. The state should be careful not to overtask officers by over-criminalizing, allowing officers to focus on criminal activity that represents the biggest threat to public safety.

The state should also ensure that the police have what they need to successfully enforce the laws. This not only includes resources to departments, but also includes ensuring that if an offense occurs there is a timely effort to prosecute if the case warrants it. Otherwise, officers can be left feeling like their work is in vain. Speaking of culture, citizens can do a better job in not treating high profile, tragic exceptions as if they are the rule.

Our criminal justice system can be made fairer. As a state, we can decrease both justice system involvement and crime rates with better education, more job opportunities and smarter criminal justice policy. These goals are not mutually exclusive, but complementary. We can make our streets safer. We owe it to officers Deen, Tate, McKeithen, Blair, Robin, Estorffe, Harris and Patterson, as well as so many more, to try.