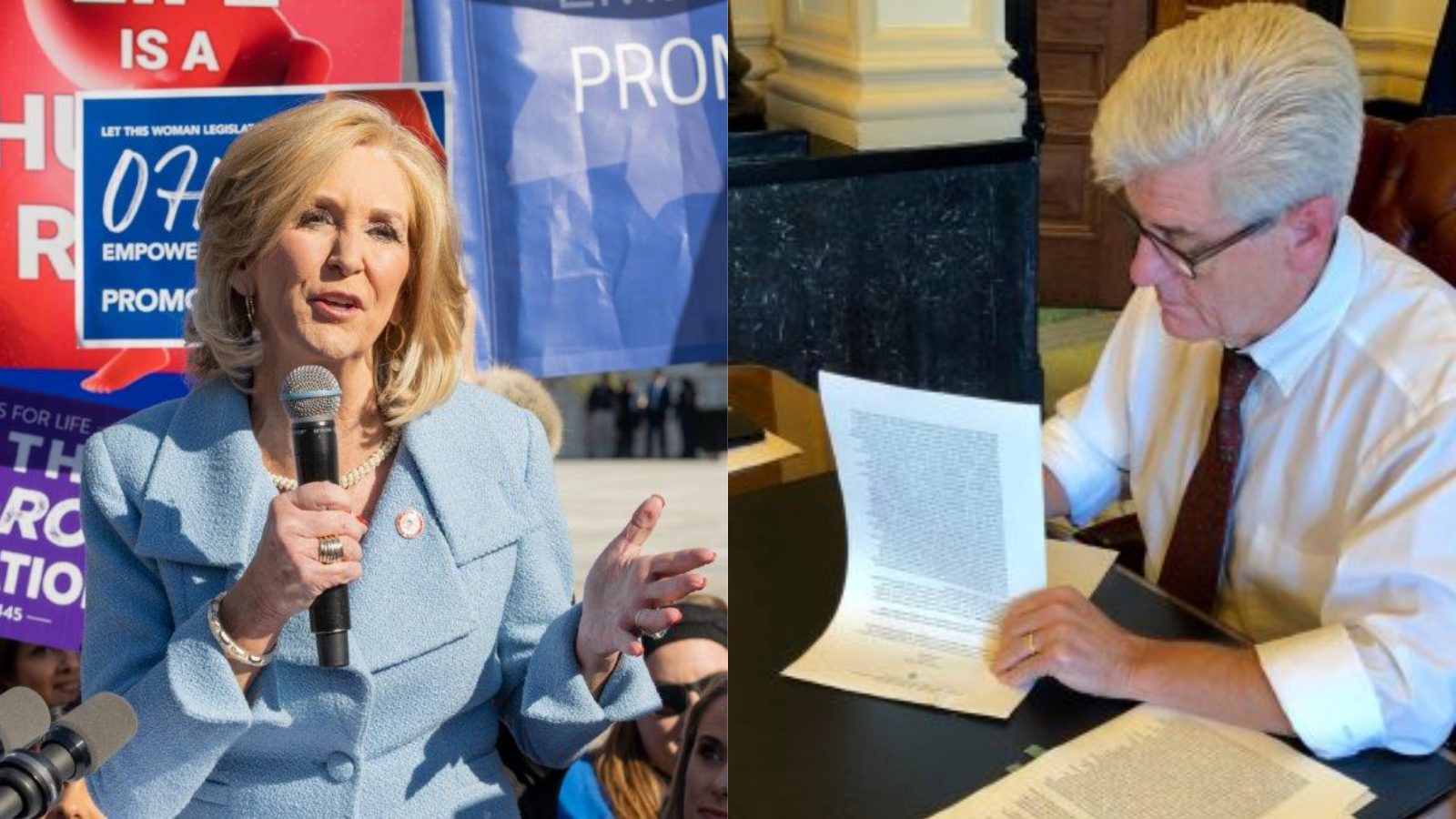

Lynn Fitch and Phil Bryant

Written by Mark Hemingway, RealClearInvestigations

In spite of the pressure, Mississippi never wavered from questioning the viability standard as the basis for legal abortion.

Erin Hawley didn’t know that she would help make history when she took a job in February with the conservative legal group, Alliance Defending Freedom. Two months later, the former law professor was on a plane to Mississippi to serve as co-counsel with the state’s attorney general, Lynn Fitch, and its solicitor general, Scott Stewart, to win the most momentous Supreme Court case in half a century – the overturning of Roe v. Wade.

“I think it was really meaningful for me because I had a 6-month-old that I actually took to Mississippi to that meeting,” Hawley said of her efforts to end the constitutional right to abortion. “It made why Dobbs matters really concrete, to be talking about this legal strategy and these issues with a baby in tow.”

The role of Hawley, wife of Republican Sen. Josh Hawley of Missouri, and the central role played by the Alliance Defending Freedom, are part of the untold story behind the case that overturned Roe and Thomas E. Dobbs, State Health Officer of the Mississippi Department of Health, et al. v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization. Their relative anonymity was not an oversight, but instead part of a deliberate strategy reflecting the political sensitivities of today’s partisan political landscape.

Though Erin Hawley was a Supreme Court clerk under Chief Justice John Roberts and her legal acumen is not in doubt, her husband, a former state attorney general, is a bête noire of abortion activists and other liberals. Knowledge of her involvement behind the scenes would have been an unwelcome distraction to her legal team.

And although the Alliance Defending Freedom has won 14 victories at the Supreme Court since 2011 – including affirming Christian bakers’ right to refuse making custom cakes for gay weddings and the right of churches to receive taxpayer-funded state grants – it kept its role under wraps for fear of attacks to undermine its case from progressive groups such as Southern Poverty Law Center, which has designated it a “hate group” for defending traditional Christian sexual ethics.

As the state of Mississippi publicly litigated the case, it strategized closely with the alliance, which conceived of the successful legal reasoning behind Dobbs. In interviews with RealClearInvestigations, the group’s leaders detailed their internal deliberations – and the deep concerns among pro-life allies about the principles and arguments ultimately presented to the court.

The overturning of Roe v. Wade can be traced back to the day the court ruled in 1973 that there was a constitutional right to abortion. Through the decades, pro-life forces embraced various strategies to challenge that ruling with limited success.

Starting in 2016, the ADF began to focus on challenging a core foundation of Roe – the issue of fetal viability. In Roe, the high court established that abortion was legal until the unborn child “has the capability of meaningful life outside the mother’s womb,” wrote Justice Blackmun in the majority opinion. In 1992, another Supreme Court decision on abortion, Planned Parenthood v. Casey, allowed states to place some restrictions on abortion while still embracing the concept that women have a right to get an abortion before viability. At the time, it was hard to define when such viability occurred, leading some abortion-rights advocates to claim it does not occur until birth.

But ongoing scientific advances have repeatedly redefined viability in the 50 years since Roe and the 30 years since Casey. It’s now generally agreed that children can survive outside the womb after as few as 20 weeks. Along the way, the viability standard had come to be seen as beneficial for pro-life legislatures’ attempts to restrict abortion to earlier in pregnancy.

But if many in the pro-life movement came to rely on the viability standard to make incremental gains in abortion restrictions, viability remained controversial as a legal and ethical matter. “We know that at 15 weeks that a baby can do things like open and close her hands. She can open and close her eyes, can stretch and move and quite likely feel pain,” says Hawley. “So why can’t a state protect her life at that point when they can a few weeks later? It doesn’t make a lot of sense legally as a constitutional matter. It’s just junk that’s totally made up.”

At meetings in 2016, the alliance tried to get the pro-life cause on board with a new strategy. It wasn’t easy. “Candidly, it was it was difficult to get support from a number of life groups, because the consensus was, you know, you should stick with 22-week limitations or 20-week limitations,” says Kristen Waggoner, general counsel for the ADF and one of the most experienced Supreme Court lawyers in the country. “That was the strong consensus, but it was very clear that Planned Parenthood wasn’t challenging 20-week laws, because that was too close to the viability line.”

There was another challenge. Cases don’t just magically appear at the Supreme Court. There would have to be a legal conflict for the court to take up, and that conflict would have to be created. A state legislature would have to essentially pass a law restricting abortion before viability, wait for that law to be challenged under the viability standard established in Roe and Casey and then hope it would be appealed all the way up to the Supreme Court. Even then, there was no guarantee the court would hear the case, let alone rule in their favor.

“[We were] looking at specific courts, Attorney General’s offices, looking at the legislatures in the states to try to figure out where to go,” says Waggoner. “When you think about, it’s not just a campaign that you would run as a case is going through the courts. It’s also campaign that you would run to get a bill passed.”

The ADF found leaders in three states were amenable to the idea. Arkansas and Utah expressed interest in passing laws to challenge the viability standard, and both states eventually passed laws restricting abortion before 18 weeks in 2019. But Mississippi moved more quickly. After reaching out in December 2017, the ADF soon found leaders in Mississippi were also open to the idea. “We had some allies on the ground and the governor’s office down there, which was Governor [Phil] Bryant at the time, so the legislation took off. The legislators loved it,” says the alliance’s director of government affairs, Kellie Fiedorek.

Pro-life politicians in Mississippi had already been working on legal challenges to abortion. In April 2012 the state passed a law requiring doctors performing abortions to be board-certified obstetrician-gynecologists and have admitting privileges at an area hospital. The law was effectively struck down when the Supreme Court in 2016 refused to hear the case. Given another opportunity to overturn Roe, Mississippi leaders jumped at the chance.

In March 2018, the state legislature passed the Gestational Age Act, restricting abortions in Mississippi after 15 weeks – well before the accepted viability line. Right after signing the bill, Bryant remarked: “We’ll probably be sued here in about a half hour, and that’ll be fine with me. It is worth fighting over.”

The state was, in fact, promptly sued by the state’s only abortion clinic, Jackson Women’s Health Organization. In November 2018, a federal judge in the Southern District of Mississippi invalidated the Gestational Age Act, and that ruling was appealed. In December 2019, the federal Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals upheld the lower court’s ruling on the ground that the law violated the viability standard created by Roe and Casey. There was only one place left to appeal. The plan to get Dobbs v. Jackson before the Supreme Court was afoot.

Still, in the years a case winds its way through the legal system there is plenty of time for things to go wrong. Of particular concern was a lack of continuity between state officials charged with defending the Gestational Age Act, given that the state’s defense of the law depended on elected officials who come and go.

The Fifth Circuit had ruled against the state in December 2019 – and the following month in Mississippi a new governor, Tate Reeves, and a new attorney general, Lynn Fitch, would take office.

The new officials pursued the conservative legal strategy they inherited with equal zeal. Fitch’s office petitioned the Supreme Court to hear Mississippi’s case in June 2020. Three months later, liberal Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg died. A Republican Senate quickly confirmed Notre Dame law professor Amy Coney Barrett, and suddenly Republican-appointed justices comprised a solid 6-3 majority on the court. The possibility of the Dobbs case overturning Roe started to seem real.

With a lot riding on the case, Fitch appointed Scott Stewart as solicitor general, a role which would ultimately make him the lead litigator in Dobbs v. Jackson and responsible for conducting the oral arguments before the Supreme Court.

Aside from being a former clerk to Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas, Stewart was notable for being at the center of an earlier controversy when he was working for the Justice Department. A 17-year-old illegal immigrant who was staying in a federal shelter had obtained a court order to get an abortion, and the Trump administration’s Justice Department told the girl she would have to go through with the pregnancy or leave the country. Stewart was the Justice lawyer tasked with defending the government’s position, which was rejected by a federal judge, who allowed the underage girl to go through with the abortion.

Now, the Supreme Court having granted a petition for its review of the Mississippi law on May 17, 2021, it limited the review to only one question presented in the state’s appeal: “Whether all pre-viability prohibitions on elective abortions are unconstitutional.”

As the stakes for the case rose, so did the internal pressure and second-guessing. “I can tell you without naming names that many, many people who were advising Mississippi informally said that they were crazy to ask for Roe to be overturned in full – that this could backfire and lead the court to strike down the law under existing precedent. And that the most they could hope for was a slight tweak to existing precedent to allow 15-week laws, but not much more,” says Sherif Girgis, a law professor at Notre Dame. “We can easily forget that just a few months ago, it seemed to a lot of seasoned court watchers to be insane for Mississippi to ask for this.”

In spite of the pressure, Mississippi never wavered from questioning the viability standard as the basis for legal abortion. “The Attorney General of Mississippi Lynn Fitch, and the SG Scott Stewart as well, I think they both deserve a huge amount of credit for going whole hog,” says Ryan T. Anderson, President of the Ethics and Public Policy Center. “I think it was a good strategy of bringing the Mississippi law limiting abortion to 15 weeks, to make them realize how radical [our abortion] law is – 15 weeks puts us in line with [abortion restrictions] in Europe, and no one thinks Europe is like the religious right.”

With a 6-3 conservative majority on the court, it might be tempting to reduce the outcome of Dobbs v. Jackson to GOP machinations in the appointment and confirmation of Supreme Court justices. But the legal team defending Dobbs also benefited from a widespread sentiment even among liberal legal scholars that Roe v. Wade rested on shaky legal ground. Harvard law professor and prominent constitutional scholar Laurence Tribe has said, “One of the most curious things about Roe is that, behind its own verbal smokescreen, the substantive judgment on which it rests is nowhere to be found.” Even Justice Ginsburg – a pro-choice advocate who remains an icon among the progressive left – described Roe as a “heavy-handed judicial intervention [that] was difficult to justify and appears to have provoked, not resolved, conflict.”

Given that defending existing abortion precedents on the legal merits was a difficult task, the opposing litigators tasked with defending the right to an abortion also adopted a maximalist position that didn’t leave the court room for compromise.

“The biggest mistake I think the opponents of the Mississippi law made was to refuse to give the court a middle ground,” says Girgis, “to refuse to give the court a way to uphold the regulation while still leaving intact some right to an abortion. Obviously they didn’t want to give the court a way to strike down a way to uphold the regulation period. But the fact that they kept saying there’s no middle ground made it easier for the court to say: ‘Look, our hands are tied. We just have to decide thumbs up/thumbs down on Roe and on the constitutional rights on abortion.’ ”

Waggoner, who’s set to present oral arguments before the court for the third time this fall, was also taken aback. “I was surprised that the lawyers basically told the court it’s one way or the other here, you either have to reverse Roe and Casey or you don’t,” she says.

Facing the weakness of the legal arguments underpinning Roe and the conservative majority on the court, Girgis thinks that the opposing lawyers in the case may not have even tried to preserve the existing precedent. “The calculation there seems to be that for the sake of the pro-choice cause, it’s better to lose big than to lose small,” he says. “If Roe and Casey are overturned in full, and the American people know that there’s now no constitutional right to an abortion, that has a better chance of rallying people to restore the right [to an abortion] politically.”

The Center for Reproductive Rights, which tried the case for the opposing side, did not respond to a request for comment.

With neither side presenting an argument that pointed the way to a compromise that would allow the court to uphold the existing abortion precedents, the conservative majority on the court went ahead and overturned a 49-year-old precedent. A legal victory that had been doggedly pursued by two generations of conservative legal scholars and pro-life activists had been achieved.

The Dobbs victory, which is a product of outside groups working with elected officials to engineer a favorable Supreme Court outcome, may also have a lasting effect on the legal strategy for the conservative movement going forward.

Former Governor Bryant observes that the ADF’s efforts to aid Mississippi were of tremendous value in Dobbs. “When the Alliance Defending Freedom came in, it was the emphasis that we needed to begin this process,” he says. “You need outside legal review… and [someone] watching the [legislative] language, understanding what judicial scrutiny it’s going to come under, and understanding that the media are going to hype this.”

As for the efforts to prod the court, that strategy seems vindicated as well. “The left has filed preemptive litigation at least since the civil rights era and they have effectively advocated in the public square for their position, not just to defend the truth, but to be assertive about it. And I think that [the Dobbs victory] vindicates that on the conservative side as well,” says Waggoner.

In this respect, the Dobbs victory is the result of embracing an activist legal strategy that many conservatives who care about constitutional order haven’t been entirely at ease with. But other conservative activists have long argued the pro-life movement was a moral cause on par with the civil rights movement – and ignoring the strategies commonly used to get the Supreme Court’s attention would amount to unilateral disarmament in a lot of important legal battles. “The fact that you’re percolating those issues up to the Supreme Court is sending a message to the court, this is coming, this is coming, this is coming, you’ve got to deal with this,” says Waggoner. “And it creates this momentum, that isn’t just a momentum in the law, but a momentum in the culture.”

Whatever Dobbs portends for the future of conservative legal strategy, after six years of careful legal maneuvering it’s hard to argue with winning the biggest Supreme Court case in five decades. “I lost a lot of sleep,” says Waggoner. “I think it felt like a dream in certain moments – an almost unrealistic dream that was too big to even imagine.”

###