Studio portrait of Sid Salter. (photo by Beth Wynn / © Mississippi State University)

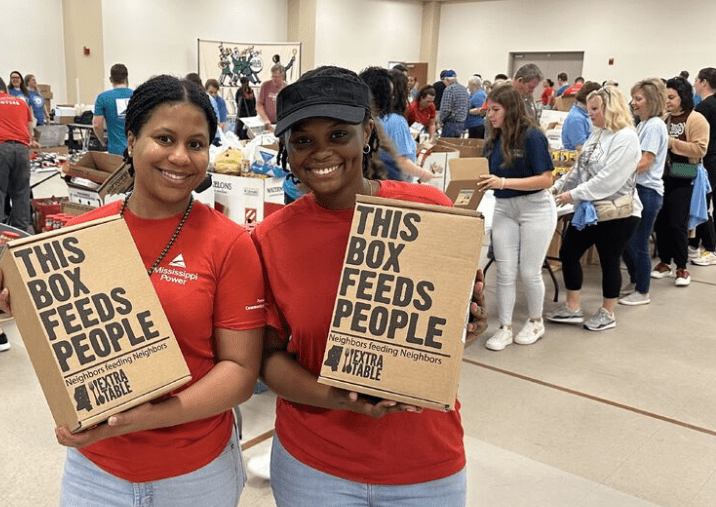

By: Sid Salter

Mississippi spends just under $350 million annually operating our state’s prison system – some $30 million less than in 2014. During a 2018 visit to Gulfport, President Donald Trump heaped praise on Mississippi for a series of corrections reforms he said would become a model for the nation.

Within weeks, with Trump signing the federal First Step Act, the Mississippi reforms became that model. Much of Trump’s admiration came as a result of Mississippi’s 2014 adoption of House Bill 585. But five years later, critics allege that law promised far more reform than it delivered.

As lawmakers return to Jackson for the 2020 regular session in January, Corrections is a state agency looking for additional personnel and additional funding to make the programs promised in 2014 more of a reality. Revisiting the initial promises of House Bill 585 would be a good start, say judicial and corrections system officials alike.

Their message? Reinvest some of the savings realized by House Bill 585 into the operation of state prisons. But the state didn’t get into this situation overnight and the fix won’t likely be quick, either.

A new study also questions the wisdom of Mississippi’s habitual offender laws as contributing to the state’s high incarceration rate and the associated taxpayer burden it creates.

In 1995, Mississippi lawmakers took what they believed at the time was a bold step toward getting tough on crime. But in doing so, the lawmakers also dramatically increased the state’s prison population and therefore the operating costs of the state prison system.

The Legislature adopted the so-called “85 percent rule” which mandated that all state convicts must serve at least 85 percent of their sentences before being eligible for parole. Mississippi’s law was in sharp contrast to other states, where the 85 percent rule applied only to violent offenders.

There were other factors for adoption of the law as well. First, lawmakers were scrambling to help the state qualify for federal funding under a federal crime bill. Second, lawmakers had grown frustrated with erratic discretionary swings by former Parole Boards between periods of tough and then lax parole standards. That brought pressure on lawmakers to stabilize paroles. Many believed the “truth-in-sentencing law” would accomplish that.

Finally, “truth-in-sentencing” rode to passage on the cycle of both rising overall FBI index crime rates and rising violent crime rates in the decade prior to legislative adoption of the law. Public support for adoption of the law was vocal and solid.

But the unintended consequences of the law were alarming. Mississippi’s prison population soared from 12,292 at the end of the 1995 fiscal year to 31,031 at the end of the 2005 fiscal year. A subsequent National Conference of State Legislatures report called “Principles of Effective State Sentencing and Corrections Policy” outlined the broader impact:

“Mississippi’s state prison population more than doubled and corrections cost increased three-fold following passage of a 1995 truth-in-sentencing law… .To deal with swelling prison populations and costs, the Mississippi Legislature twice increased the amount of good-time that low-level offenders were eligible to earn and reinstated parole eligibility for certain non-violent offenders. In 2008, lawmakers reinstated discretionary parole at 25 percent of the sentence for inmates convicted of non-violent crimes who have no violent history.”

In 2014, Gov. Phil Bryant signed prison sentence reform legislation that supporters claimed could save Mississippi some $266 million over the next decade. House Bill 585 required those convicted of violent offenses to serve at least 50 percent of their sentences, while those convicted of nonviolent offenses would serve at least 25 percent before being eligible for parole.

In short, the state’s rising prison population finally put state government in the mode of reducing the number of inmates housed in the custody of MDOC Mississippi joined other states in commencing a downsizing driven primarily by budgetary concerns. Leading up to the 2014 reforms, Mississippi was simply warehousing too many non-violent offenders for unreasonable periods of time and the taxpayers got hammered over the rising costs.